copyright 2009 by George Johnson

Subdivided. (Edinburgh shop window). photos by George Johnson, copyright 2009

1. Retrofit Arithmetic (and Rainbarrel Economics)

2. The San Juan-Chama Shell Game

3. The Case of the Disappearing Aquifer

4. The Creative Hydrology of Suerte del Sur

5. The City, the County, and a Water Tax Revolt

6. Water Numerology at City Hall

(Our story thus far)

7. The Woman at Otowi Gauge

8. "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."

9. The Las Campanas Connection

(Our story continues)

10. The Engineering Solution

July 9, 2009

61. Magic Mountain

If, God forbid, someone were to build a subdivision next to me, I'd want it to be Doug McDowell. The consideration he has shown to neighbors of Mirasol, his proposed development at the foot of Sun Mountain, goes far beyond the strategic pandering one has come to expect from other developers. For that reason it was easy to appreciate the Journal's recent editorial supporting the project.

But on two points I think the editorial was wrong. The first is a minor one: The fact that Sun Mountain is not as high as Atalaya or Picacho (whose real name, I will insist until my dying day, is Talaya) does not diminish its importance as a vista worth protecting. Its proximity magnifies its height. If Shirley MacLaine, Andrew Davis, or Tom Ford managed to prop a house on top of Sun Mountain, the impact would be greater than a mansion on the higher and more distant Atalaya.

My bigger disagreement was with the editorial's underlying premise: that the purchaser of a property has a fundamental right to develop it to the maximum extent consistent with the law. The 23-acre Watson property is zoned R-1 (one residential unit per acre). The Journal suggests that the neighbors should be grateful that Mr. McDowell plans to build only 13 additional houses.

It's this kind of reasoning that has been eating away at this town. What Mr. McDowell purchased from the Watsons was a single family home on three legally platted residential lots. If he wanted to build two more houses, no one could reasonably complain. But the conversion of three lots into 14 is a very big deal -- more traffic, more noise, more strain on utilities. No matter how green the houses or how many are defined as affordable, the only real beneficiary would be Mr. McDowell, and he would be benefiting at the expense of his neighbors.

At last week's Planning Commission meeting, the Journal reports, Kim Shanahan, president of the Santa Fe Homebuilders Association, spoke in favor of Mirasol and admonished the commissioners (he used to be one) to base their decision strictly on whether the development conforms to city code. But then why even have a Planning Commission? All land-use decisions could be made algorithmically by a computer. Conforming to the letter of the law should be the minimum requirement, the starting point for deliberations. The reason we have citizen commissions is to balance interests and weigh intangibles.

One of the most passionate condemnations of Mirasol came in an op-ed piece several weeks ago in the New Mexican: Sun Mountain: treasure, or mere commodity?

Santa Fe is blessed with a lovely set of mountains supported by a range of captivating foothills, all of which are particularly attractive while viewing or approaching from the southwest. Except of course when, upon closer examination, one notices all the monuments built to satisfy the egos of their owners who rejoice in their westward views. . . .

Mirasol, the writer continued, "is the result of totally inadequate forward thinking by the owners, by the city planners, by those responsible for the wise use of our limited resources, and by those in the city who still are unable to balance short-term greed with the long-term needs and amenities that have made Santa Fe what it has been for the past 400 years. In every organism, there is a tipping point. Could this unnecessary Sun Mountain development be the tipping point launching Santa Fe's decline into the ordinary?"

You might think you were reading a brief from the Wild Earth Guardians -- until you notice the byline: Gregg Bemis, the right-leaning New Mexican columnist who, as it happens, lives across the street from Mirasol on Old Santa Fe Trail.

Over the years, Mr. Bemis's Limbaugh-like remarks about national health insurance (the work of "socialist do-gooders") or taxes ("a collectivist punishment") had led me to lump him with those free-market absolutists who insist that everyone has the right to do whatever he wants with his own property. It was good to learn that Mr. Bemis takes a more nuanced view.

Wherever we live, the value of our homes and the comfort they bring us depend on the cooperation of our neighbors and their willingness to consider more than the bottom line. Left or right, Democrat or Republican, no one would really want to live in a world where everything is determined by the market.

July 16, 2009

Radioactivism

On a spring day in 1976, I walked into the offices of The New Mexico Independent on Central Avenue in downtown Albuquerque to inquire about an article I'd dropped off, unsolicited, about uranium mining in New Mexico. Since I hadn't heard back from the editor, Mark Acuff, I was prepared for another rejection. I was surprised when, as soon as I walked through the door, I heard Mr. Acuff's voice booming from the back of the room. It took me a moment to realize that he was reading my story, which had already been typeset, out loud to a proofreader. It was featured on the cover in the next edition of the paper and later republished in the Mountain Gazette.

I was reminded of the story this morning when I read a column by Tracy Dingmann, also about uranium mining, in what is now called The New Mexico Independent. Mr. Acuff and his paper are long gone. Though the names of the publications are identical, the only connection, I believe, is coincidental: V.B. Price, who wrote for Mr. Acuff, now writes for the online Independent.

I learned from Ms. Dingmann's column that today is the 30th anniversary of something called the Church Rock uranium spill, in which an earthen dam on a milling pond broke releasing mildly radioactive mining tailings into the Rio Puerco. Like Ms. Dingmann I hadn't heard of the event, which is described by an Albuquerque environmental group, Southwest Research and Information Center, as a major nuclear catastrophe:

More radiation was released in the spill [SRIC states] than in the Three Mile Island reactor accident, which occurred in March of that same year, and the spill ranks second only to the 1986 Chernobyl reactor meltdown in the amount of radiation released.

Like the old Independent, the Southwest Research and Information Center is a blast from my past. It occupies the same house on Stanford, near the University of New Mexico, that it did when I was a student. One of my first articles for the school paper, the Daily Lobo, was a profile of Charles Hyder, a physics professor, SRIC staff scientist, and anti-nuclear activist. I no longer have a copy, but I suspect I'd be embarrassed now by my credulity. From the very beginning, the SRIC has known how to bend the news to fit its agenda.

Contamination from mining near Church Rock was worrisome enough for the area to be declared an EPA Superfund Site. But the significance of the Church Rock spill itself is harder to evaluate. A 1983 article in the New York Times called the incident "the largest accident involving nuclear waste in the history of the industry." Maybe we should be relieved that a quarter century later Church Rock is still being billed that way. The article also noted that "investigators from Federal, state and private agencies have concluded that the danger to people and livestock living along the river is minimal." A study published in the journal Health Physics seems to bear that out. According to an abstract, there were "no detectable elevations above background concentrations" of radioactive elements in people living by the Rio Puerco and "estimated exposures do not exceed existing state or federal regulations." Breathing the dust, the authors projected, might cause 204 millirems of exposure over 50 years. By comparison, living in Santa Fe, at 7,000 feet altitude, subjects a person to an estimated 53 additional millirems from cosmic rays in just one year.

Maybe the reason almost no one has heard of the Church Rock spill is because it wasn't all that serious. There is no question that abandoned uranium mines in western New Mexico have created environmental hazards. (Take a look at this EPA comic starring Gamma Goat and Rad Rabbit.) If exaggerating the significance of Church Rock helps draw attention to the bigger picture, maybe that is o.k. But comparing the incident to Chernobyl is absurd and undermines the credibility of any environmentalist or reporter who repeats the claim without further research. I wish Ms. Dingmann and Sue Major Holmes, the Associated Press reporter (and another blast from my past) who covered the 30th anniversary Church Rock demonstration, had made an effort to filter the politics from the science.

July 26, 2009

Water Pressure

For all the times I've mentioned the San Juan-Chama Project (most recently in a commentary for the Reporter's 35th anniversary issue), it has been little more than an abstraction for me -- a blurry mental map of dams and tunnels that move water normally bound for the Colorado River into the Rio Grande. Finally, a couple of weeks ago, the concept became concrete.

I was driving home from Chimney Rock, Colorado, where I'd gone to see an archaeological dig with Steve Lekson, the subject of a piece I wrote recently for the Times. When I got to the town of Chromo I turned east onto a dirt road that follows the Navajo River -- a tributary of the San Juan, which, in turn, feeds into the Colorado. Six miles later I reached my destination: the Oso Diversion Dam. It apparently doesn't get many visitors. I stepped over the locked gate, walked to the edge of the dam, and looked down at the sluiceway where a sliver of the Navajo is peeled off and shunted into an underground tunnel that leads south toward New Mexico.

From Oso the current enters the Azotea Tunnel for a trip beneath the Continental Divide, ending up in Heron Reservoir on the Rio Chama and eventually spilling into the Rio Grande. Water from two other San Juan tributaries, the Little Navajo and the Rio Blanco, is also funneled this way. Altogether an average of 110,000 acre-feet of water a year is transferred from one river basin to another. Without its share Santa Fe would not survive.

Back on Highway 84, I drove over the Continental Divide, following the path of our water supply. Just before the village of Tierra Amarilla, I detoured west to Heron Lake. It was full and blue, so beautifully out of place beside the dry New Mexico mesas. Continuing south along a muddy county road to El Vado -- the next reservoir downstream on the Chama -- I thought of all the other claims on San Juan-Chama water. Albuquerque, Española, Los Alamos, Pojoaque, Nambe, San Ildefonso, the Jicarilla Reservation, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, Bernalillo, Los Lunas, Belen -- all these and others are depending, like Santa Fe, on there being enough imported water to go around.

Further up the chain the competition is even fiercer. Before water is diverted from the Colorado watershed and sent to New Mexico, the demands of the Navajos and the Utes must be met. More than half a million acre-feet -- five times the average San Juan-Chama flow -- has been allocated by Congress to the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project. The Utes have been promised another 66,000 acre feet when the Animas-La Plata Project is complete. All these designs on Upper Colorado River water must be balanced against the claimants lower down: Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles.

Back home in Santa Fe I drove out one afternoon to the old Buckman town site where, after years of pressure from the State Engineer (New Mexico's water czar), the city is building a diversion dam to take its San Juan-Chama water directly from the Rio Grande. Way back in 1972 the state issued what is called a dedication permit, allowing Santa Fe to pump water from the Buckman aquifer while it went about constructing a diversion. The wells were supposed to be temporary. But the city just kept on pumping, for decades, pretending that its San Juan-Chama water, percolating down from the Rio Grande, was replenishing the water table and balancing the hydrological books. In fact, the water wasn't being replaced nearly as fast as it was being consumed. Much of Santa Fe's growth has been fed by mining the Buckman aquifer.

The Buckman Direct Diversion will help put an end to the thievery. Just west of Diablo Canyon, construction was progressing on a large sand-filtering contraption and on a long pipeline that will conduct the diverted river water to a new treatment plant near the Marty Sanchez golf course. As I drove back in that direction, past the latest extrusion of Las Campanas sprawl, I listened on the radio to a deejay broadcasting live from a new Centex development off Cerrillos Road. For all Santa Fe's pretensions about sustainability, it continues to behave as though it can grow forever. What's scary is that every other city dependent on Colorado River water is acting the same way.

August 11, 2009

Cash for Hovels

My Jeep Cherokee recently turned 17 years old making me a natural candidate for the government's Cash for Clunkers program. By surrendering my car at a local dealer, I could receive $4,500 toward the price of a new Prius, reducing my cost to around $20,000 and increasing my gas mileage from an official 17 miles per gallon (I actually get more like 20) to 50 mpg. Since I drive about 8,000 miles a year, that would reduce my fuel consumption from about 470 gallons to 160. At $3 a gallon that means an annual savings of $932. In 22 years my new car would have paid for itself. With $4 gas the payoff would still be 16 years. I decided to keep the Jeep.

It wasn't only about the money. The new Prius would be far more energy efficient and fun to drive. But how much energy did it take to manufacture the car? Iron ore had to be mined and smelted into steel. Copper had to be spun into wire. Plastics had to be synthesized from petroleum and other chemicals. Sand had to be melted to make glass. I'm saving all that energy by not buying a new car. Eventually I'll have to, but every year I wait I'm reducing my impact on the environment.

The real dealbreaker came when I learned what Cash for Clunkers would do to my Jeep. With only 126,000 miles on the odometer, it is not really a clunker. The engine is strong and doesn't use a drop of oil. The transmission and the rest of the power train are in good condition. Under the program, this precision machinery would be destroyed. The oil would be drained from the crankcase and replaced with sodium silicate -- liquid glass -- causing the pistons to seize. Then the vehicle would be crushed or shredded, along with hundreds of resalable parts that might have kept more old Jeeps running for awhile. Multiply that by the hundreds of thousands of buyers expected to participate in the program and the waste is staggering. But as I drove away in my new Prius, I could tell myself I was being green and, of course, helping the economy.

These thoughts were on my mind yesterday when I read that Mayor Coss was planning to speak at the grand opening of The Emerald Home in the Monte Sereno subdivision near the Santa Fe Opera. Billed as "a true net-zero home, showcasing innovative design, materials, building systems and renewable energy," it covers 4,125 square feet -- almost double the footprint of an average-sized house -- and is priced at $2.5 million.

According to a news release, the City of Santa Fe has been quick to endorse the concept. "We're excited to be on the cutting edge to achieve the City's goals of creating a green and sustainable city," said Jack Hiatt, the City Land Use Director. Faren Dancer, the entrepreneur who built the house, said: "I'm proud to be part of a community with the vision to guide its destiny toward a sustainable future."

But there is nothing environmentally farsighted about a single-family home that is twice the normal size -- meaning that it took approximately twice as many resources to build. The energy savings from living in The Emerald Home will be dwarfed by the extra energy consumed in construction.

Taking this kind of thinking to the extreme, the Cash for Clunkers program could be followed by Cash for Hovels. I could bulldoze my old house on San Acacio, haul the rubble to the dump, and use my government rebate to build a bigger LEED Certified replacement. If enough people followed suit, Santa Fe would become The Emerald City. We'd all be living in the Land of Oz.

August 13, 2009

Beer and Water

In anticipation of the mayor's state of the city address this week, the Reporter asked some Santa Feans for their impressions. Here, for the record, is what I said:

First the good stuff: The city is letting water flow in the river -- enough to keep the upper bosque alive. Graffiti is under tighter control. Trash cans no longer sit on the curb for days because of a broken truck or a sick-out. But some things never seem to change. The burglary rate is spiking again despite the hiring of all those new police officers. "Lifestyle crimes" -- like noise pollution from rolling boom boxes -- continue to be ignored. Motorcycles and muscle cars roar mufflerless through town while the cops look the other way.

A day later, I'm feeling much less optimistic about the river. At last night's City Council meeting, our representatives, it seems, were less interested in flowing water than they were in beer. After a lively debate, they voted to approve a rathskeller for the city's 400th Anniversary festivities (with the drinks sold by Gerald Peters's Blue Corn Cafe). But the bigger story was the Council's passage of a new water budget in which the water conserved by residents will primarily subsidize more development. Priority will be given to affordable housing and small developers. But according to the New Mexican, the Council denied a request by the Santa Fe Watershed Association, the City of Santa Fe River Commission, the Northern New Mexico Sierra Club, the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, the Wild Earth Guardians, the Santa Fe Farmers Market, and other groups to include a line item for the Santa Fe River.

Under the new law, the City is free to allocate any leftover water the developers don't buy to other projects, including river restoration. But as in the past, a living river will be strictly a voluntary proposition.

Postscript

In the posting above, I'd originally noted that the New Mexican "relegated to a brief" the news about the water budget. That was unfair. The reporter, Julie Ann Grimm, tells me that the debate pushed right up against the paper's deadline. We'll watch for a followup story tomorrow. Meanwhile Bill Depuy at KSFR has pointed me to his detailed report on the meeting, including testimony about the water budget from the Watershed Association's director, Dave Groenfeldt. Here is an audio clip. Finally Frank Katz, the City Attorney, says that because of some amendments, still to be recorded, the new ordinance is more favorable to the river than I give it credit for. I hope so. Please check back for more on this.

August 16, 2009

I thought for sure that by Sunday morning -- three full days after Wednesday night's Council meeting, either the New Mexican or the Journal would have explained the import of the new water budget ordinance. But there has been nothing in either paper. The original proposal contained the word "river" exactly one time: at its discretion the Council could allocate leftover water, should there ever be such a thing, for keeping the Santa Fe River alive. Another clause allowed any citizen who installs and certifies water-conserving devices to donate the droplets saved to a project of his choice -- anything presumably from a public water slide to river restoration. But unless the ordinance has been amended to require that some of the water the city conserves go back to the river, it will remain as vulnerable as ever to the pressures of development. The City Attorney has promised to send me a copy of the amended law as soon as it is ready. But a town with two competing newspapers shouldn't have to wait so long for such important information.

August 19, 2009

Barnstorming

Not long after my dispatch of July 26, I heard from a reader, Thomas Blog, who ran unsuccessfully five years ago for Santa Fe County Commission. He is now studying law at UNM. Mr. Blog is also a pilot, and he recently flew along the route of San Juan-Chama water, from Cochiti Dam south of Santa Fe all the way past Heron Lake near the Colorado border. Here is his aerial shot of the point where the Azotea tunnel emerges, just above Heron, spilling water diverted from the San Juan basin into a tributary of the Chama:

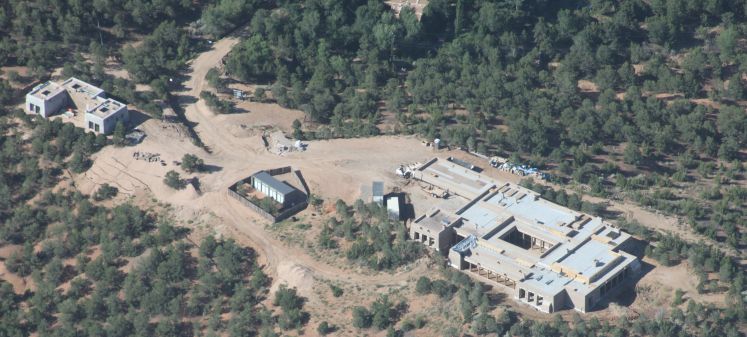

Mr. Blog sent dozens of other photos, including one of eight Exxon corporation jets parked at the Santa Fe airport. I wonder what that was about. Later he asked if there were any sites I'd like photographed on his next flyover, so I put in my order:

He took other arresting pictures, which I will post here soon.

August 21, 2009

Before turning the page onto a new chapter of The Santa Fe Review, here are updates on some matters we've been following:

Indian School. Senator Tom Udall has yet to acknowledge my letter, received by his office more than two months ago, asking him to ensure that the Inspector General of the Interior Department is investigating the mysterious and probably illegal destruction of the historic Indian School buildings. (The Old Santa Fe Association and the Historic Santa Fe Foundation continue to be of no help in pressing the matter.)

I know the Senator and his wife, Jill Cooper, well enough to chat when we occasionally encounter one another -- at a concert, a restaurant, or once on Atalaya Trail. I've resent my letter in care of her to their home address on Camino de Cruz Blanca. Maybe that will elicit a response.

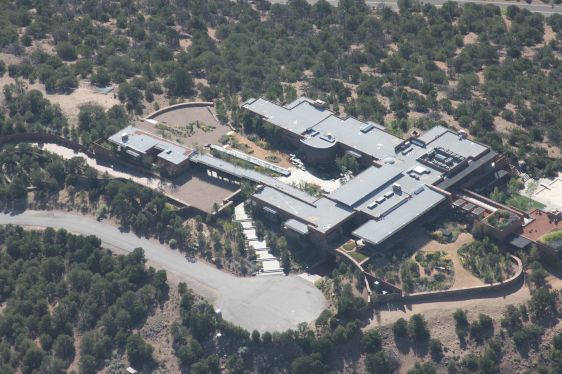

Mansion watch. Earlier this month Phaedra Haywood of the New Mexican reported that the enormous Davis estate is not yet on the tax rolls. County Assessor Domingo Martinez says that after a year of prodding he hasn't been able to get the information he needs to calculate the property's worth. The lawyer for the Davises, Frank Herdman, insists that his clients are cooperating, so it's hard to know what to think. This may partly be a case of grandstanding by Mr. Martinez, who has been trying to persuade the county to increase the size of his staff. The estimated annual taxes on the Davis property -- as much as $65,000 -- would probably pay the salary of at least one new county employee.

Sun Mountain. Last night the city Planning Commission approved the Mirasol subdivision, described in the first entry on this page. Meanwhile, the New Mexican reports, neighbors have raised more than 80 percent of the $3.2 million they would need to buy the land from Mr. McDowell and stop the development. With more than 1,200 houses for sale in town and hundreds more just outside the city limits, I wonder how firm his price is.

Water. Unless there is a wave of last-minute thunderstorms, this summer's monsoon season will be a bust. According to the New Mexican's weather charts, Santa Fe has received a little more than 5 inches of precipitation this year -- about half of normal. As a result water consumption has spiked. According to the most recent report (for the week ending August 16, available here), Santa Feans were using 12.94 million gallons a day -- a 1.65 million-gallon increase over last year. On August 18 (the most recent daily report) the figure was 13.45 million gallons.

Despite the bone-dry weather, the upper canyon reservoirs remain at a healthy 74 percent capacity, and the city continues to make good on its policy of returning, on average, 2 cubic-feet per second to the river. Approximately the same amount (1.24 million gallons per day = 1.9 cubic-feet per second) is still coming in from the watershed, replenishing the supply. But without rain in the mountains, the flow is diminishing every day.

Coming pretty soon: The College of Santa Fe

A Special Report: The Mysterious Destruction of the Santa Fe Indian School

The Andrew and Sydney Davis Webcam

A Stroll Along Shirley Maclaine Boulevard

The Santa Fe Review

More links:

See the current flow of the Santa Fe River above McClure Reservoir with the USGS automated gauge.

The Otowi gauge shows the flow of the Rio Grande north of Santa Fe.

Santa Fe water information, a collection of documents and links

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|