copyright 2006 by George Johnson

photo by George Johnson, copyright 2006

1. Retrofit Arithmetic (and Rainbarrel Economics)

2. The San Juan-Chama Shell Game

3. The Case of the Disappearing Aquifer

4. The Creative Hydrology of Suerte del Sur

5. The City, the County, and a Water Tax Revolt

6. Water Numerology at City Hall

(Our story thus far)

7. The Woman at Otowi Gauge

8. "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."

9. The Las Campanas Connection . . . desalination word games . . . and Aamodt South

(Our story continues)

10. The Engineering Solution

11. The Sorrows of San Acacio

12. The City's Dubious Water Report

13. Where the Water Went

14. Shutting Down the River Again

15. Picking on the Davises

16. The Tom Ford Webcam

17. Galen Buller's Day Off

18. Forgive and Forget

19. Election Postmortem

20. El Molino Gigante

21. Hotel Santa Fe. . . Mansion Watch . . . Water Watch

(Our story continues)

22. The Environmental Impact of Jennifer Jenkins

23. The Short-term Rental Racket . . . Water Watch . . . Mansion Watch . . . Surreal Estate

24. Archbishop Lamy's Parking Lot

25. Mayor Coss's Lost Gamble

26. Tommy Macione Swamp

27. Sweeney Center Blues

July 9, 2006

24. Archbishop Lamy's Parking Lot

The garden was walled with adobes by his first French architects, who had crafted its main entrance out of native granite. There was a sparkling fountain, and a sundial stood on a pedestal of polished Santa Fe marble. Aisles of trees, plants, and arbors led to it from all quarters of the enclosure. Formal walks reached from one end of the garden to the other, with little bypaths turning aside among the flower beds and leading to benches cunningly placed in the shade . . .At the south end of the garden on its highest ground was a spring which fed a pond covering half an acre. From the pond flowed little graded waterways to all parts of the garden. In the pond were two small islands on one of which stood a miniature chalet with a thatched roof. Little bridges led to the islands. Flowers edged the shores, and water lilies floated on the still surface, and trout lived in the pond and came to take crumbs which the archbishop threw to them. Now and then he would send a mess of trout over to St Michael's College to be cooked for the scholars. . . .

Sweeping the long shady vista and its bright colors of fruit and flower with a gesture, he would say that the purpose of it all was to demonstrate what could be done to bring the graces and comforts of the earth to a land largely barren, rocky, and dry. -- Paul Horgan, Lamy of Santa Fe

There is not much left of Archbishop Lamy's garden, just a few lilacs and an unkempt patch of gravel and wildflowers that was recreated as an afterthought, more than a century after his death. A bit of lavender and nepeta, some lilies and marguerite daisies, a single cherry tree -- all waging a struggle against dandelions, cheat grass, and sprouting Siberian elms.

Standing at the edge and looking east across the asphalt, one can imagine how it used to be: five acres of orchards and vineyards extending all the way to the Alameda. There were "Malaga grapes whose bunches finally measured fifteen inches long . . . red and white currants, plums as large as hen's eggs." There were stately (presumably not Siberian) elm trees, maples, cottonwoods, locusts, and weeping willows -- almost all of it now paved over and leased to the city for a parking lot.

A recent piece in the Journal by Karen Peterson described the final chapter in this sad tale. Scouring the newspaper archives she found a letter to the editor, apologetic in tone, written in January 1984 by two well known local developers, Al Grubesic and C. L. "Lee" Brown. Mr. Grubesic is the father of state senator John Grubesic and Mr. Brown is currently a partner with former mayoral candidate David Schutz in a plan to build a subdivision called Santa Fe Canyon Ranch near the village of La Cienega.

After negotiating with the church, the two men had struck a deal to lease about three acres of the old garden for a real estate development -- "retail establishments, professional offices, condominiums and apartments," much like what the Archdiocese is planning today. Eager to get started, they brought in some heavy machinery and, without a permit, scraped it flat, "clearing the area of debris."

As they tell the story, the garden had already been allowed to deteriorate and was now a hangout for derelicts and "poachers in recreational vehicles and mobile homes who seemed to have taken up residence." These were the days of double-digit interest rates (remember stagflation?), and financing for their project fell through. With no more need for the land, they covered it with blacktop.

The bigger issue is why the church let Lamy's garden fall into such a sorry state, and here the details are a little vague. Marc Simmons, in one of his columns on New Mexico history, quoted a Santa Fe woman who remembered that, as late as 1915, a duck pond still existed. She speculated that a new dam built in upper Santa Fe Canyon in the late 1920's (that would have been the Granite Point Dam, later replaced by McClure Reservoir) lowered the water table and dried up the spring that fed the gardens.

Whatever the cause, they were gradually allowed to wither. By the late 1960s, the garden had become "a trash heap," as Monsignor Jerome Martinez y Alire described it in last Sunday's New Mexican. "It had to be cleaned up." But that only begs the question. Was the only alternative to bury it with asphalt?

By scaling back its plans to heap a three-story development on the ruined land, the Archdiocese has regained some moral high ground. It has also opened up a heroic possibility. With all the philanthropic money available in Santa Fe, surely enough could be raised to save just one acre from the bulldozers and, perhaps with the help of the Santa Fe Botanical Garden, bring a large piece of Lamy's sanctuary back to life. Maybe Mr. Brown and Mr. Grubesic would be willing to lend a hand.

The result would be an island within whatever else the church has planned -- not another of the perfunctory xeriscapes one sees outside every office building, but something grander. Irrigation would come from the runoff shed by the roofs of the development. In a good year, with 12 inches of precipitation, that would be five extra acre-feet of water, far more than enough. In drier times maybe the Acequia Madre association could be persuaded to loan some of its flow. Who knows, if the city ever sees fit to keep a little water in the river, Lamy's old spring might even come seeping back.

Bringing back the Archbishop's garden would be a gift to all of Santa Fe, a way for the church of Anselm, Augustine, Boethuis, and Aquinas to show that life is about more than money, that land and water are not just commodities to be bought and sold.

July 14, 2006

As if Santa Fe politics were not surreal enough, imagine the scene Wednesday night at City Hall where members of the powerful planning commission were portraying themselves as populist heroes fighting the Mayor's efforts to remove them from the board. Eric Lujan, of Santa Fe Grassroots fame, and Robert Werner, who ran a memorably nasty campaign against former Green Party councilor Cris Moore, complained of being treated discourteously, while Kim Shanahan, whose belittling remarks to neighborhood groups have been a regular feature of commission meetings, depicted himself and his fellow developers as selfless public servants. Another commissioner, Michael Trujillo, spoke as though his support for the new Wal-Mart, without a proper traffic plan, was nothing less than a gift to the people of Santa Fe.

Mr. Shanahan's term has expired and he won't be reappointed. The others, who refused to resign, packed the council chambers with friends and relatives (both Lujan's wife and mother were there), cheering and booing in unison, some loudly accusing Mr. Coss of being a racist. Never mind that his nominees for the board included Estevan Gonzales, Rick Martinez, Gracie Marie Olivas, and Bonifacio Armijo (whose family owns Johnny's Cash Store on Camino Don Miguel). They were dismissed as "token Hispanics" by those who had certified themselves as the real thing.

The intensity of the anger and resentment, which began simmering during last month's hearings on the Archdiocese's plans, was unlike anything since the mayoralty of Debbie Jaramillo -- with the weirdest of twists. Among those lining up, along with development lawyer Karl Sommer, to support the commissioners were Ms. Jaramillo's own son, Angelo, and the Westside firebrand Gloria Mendoza.

Mayor Coss must be holding his head over how badly he misjudged the situation. Unaware that this would be a public hearing, the neighborhood associations had no time to pack the house with loyalists of their own. To remove the commissioners, the mayor had to show cause. But from a laundry list of potential grievances, he chose only one, Wal-Mart, driving a wedge down the middle of the Council. In the end only two of his allies, Miguel Chavez and Karen Heldmeyer, stayed with him.

"Don't gamble if you can't afford to lose," the mayor said, folding his hand. And don't come to the table unless you're sure the man with the eyeshade and the big cigar isn't dealing from a funny deck. It used to be the Jaramillo administration playing the race card against the developers. Last night was a demonstration of how skillfully some of them have managed to reverse the game.

July 16, 2006

26. Tommy Macaione Swamp

Cienega Street is called Cienega Street because it runs through what used to be a marshland -- publicly owned property that the historian Malcolm Ebright once called Santa Fe's equivalent of the Boston Commons. In Land Grants and Lawsuits in Northern New Mexico, he describes how, sometime around 1840, it fell into private hands. It's a complex story, involving Spanish land grant law and a mortgage placed on the soggy village green to cover military expenses incurred in the Battle of Pojoaque, part of the 1837 Rio Arriba Rebellion. The area, lying roughly between the New Mexican's Marcy Street headquarters and Hillside Avenue (it probably included Tommy Macaione Park) was, Mr. Ebright wrote, "a paradise lost." Now it is just real estate.

Paige Grant, former head of the Santa Fe Watershed Association, wrote to tell me that the old cienega would have been hydrologically connected to Lamy's spring. (She once spoke to a former resident of Hillside who remembers stepping carefully through the muck on his way to the Plaza. Maybe he stopped to watch Lamy's ducks.) The archbishop's pond, Ms. Grant told me, emptied into the Rio Chiquito, which flowed down what is now Water Street before emptying into the Santa Fe River.

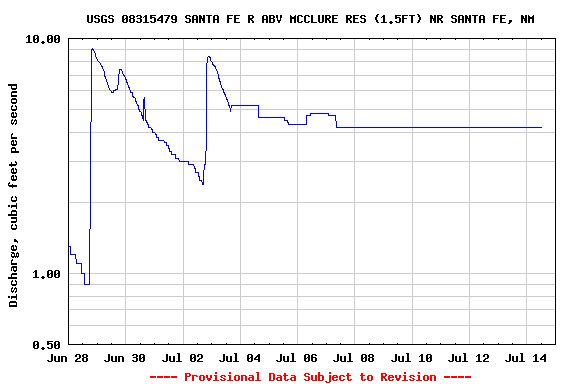

While there is no immediate danger of the swamp coming back, flooding out the Ironstone Bank, Radio Plaza, Josie's, and maybe even The New Mexican, the early start of the summer rains -- more than two and a half inches so far in July -- pushed the McClure Reservoir's intake gauge to 10 cubic feet per second (6,480,000 gallons a day) before it flatlined. Repairs, we hope, are under way. This strange phenomenon of water falling from the sky also reduced consumption last week to just 10 million gallons a day. To find numbers that good you would have to go back to 2002 when, in the midst of an otherwise miserable year, there was more than two inches of July rain.

More likely than not, this lucky streak won't last. Statisticians talk about "regression toward the mean," a fancy way of saying that things tend to even out in the long run. An example is the phenomenon called sophomore slump. If, through a combination of skill and good fortune, a young athlete plays extraordinarily well in the first season, next year's performance will probably be just so-so -- closer to the center of the Bell Curve.

Last year, wet as it was, the monsoons came late, with less than half an inch of rainfall in all of July. But the delay gave way to a more typical August and an unusually rainy September and October. Regressing toward the mean, this year's oppressively dry winter and spring were followed by these magnificent thunderstorms, bringing the accumulated annual precipitation from almost nothing to just over half of normal.

July 28, 2006

27. Sweeney Center Blues

Back when it looked as though Santa Fe might be spared the agony of so many cities that have hitched their stars to expensive new convention centers, the talk down at Lincoln and Marcy was of constructing a state-of-the-art, energy-efficient, "Green Certified" building, a model for the rest of the country. Of course even the greenest new building would take centuries to make up for the huge amount of fossil fuels spent pulverizing Sweeney Center and trucking it away, so that tons of new steel and concrete can be trucked back in. It's too late now, but after the project's latest setbacks, some Councilors must be wondering why they were so quick to tear the old gymnasium down.

As if finding an Indian burial ground beneath the parking lot hadn't been bad enough, the city received a shock this week when the only contractor who bothered to bid came in $14 million -- 33 percent -- too high. About $7 million of the excess could be cut by eliminating half the underground parking, but that would leave no more spaces than in the uprooted Sweeney lot.

We'll know in about six weeks whether the Council's gamble to open a second round of bidding pays off. (City staff says construction costs are hyperinflating by 2 to 3 percent a month.) But even if the price can be brought down closer to what the consultants predicted, it's hard to be optimistic about the effect of another megaproject (Buckman, the Railyard) on the city's bottom line.

No one expects convention centers to make money. They are loss leaders to lure visitors to restaurants, hotels, and -- if they like what they find -- real estate offices. A study commissioned by the city in 2003 strongly argued that Sweeney's small size and lack of amenities might be causing Santa Fe to lose some business. What it did not do was make a persuasive case that Sweeney couldn't have been upgraded -- with wireless Internet, a better loading dock, maybe even some underground parking and a small annex of extra meeting rooms. That might not have maximized the potential to attract hypothetical conventioneers. But it also would not have maximized the very real -- and increasing -- amount of risk the city is taking on.

Years before 9/11, meeting and exhibition space at Sweeney was going begging. Was that really because, as the consultants suggested, Santa Fe was feeling competition from hotspots like Gatlinburg and Myrtle Beach, wherever they are? Or was the place simply not being managed to its full advantage? We'll never know.

A report last year from the Brookings Institution suggests a grimmer possibility. There just isn't enough demand.

While the supply of exhibit space in the United States has expanded steadily, the demand for convention and trade show exhibit space, and the attendees these events and space bring to a city, has actually plummeted. Many cities have seen their convention attendance fall by 40 percent, 50 percent, and more since the peak years of the late 1990s. The sharp drop has occurred across a range of communities, including a number of the historically most successful convention locales in the nation. . . . The bottom line: With events and attendance sagging in even the hottest destination spots, few centers are even able to cover basic operating costs -- and local economic impacts have fallen far short of expectations.

The downtown hotels already provide some 72,000 square feet of meeting space. (The city's hired consultants said 56,770 but didn't count Hotel Santa Fe or the Lodge at Santa Fe on North St. Francis Drive.) Hotel Loretto is planning to add another 8,000 square feet, and we don't know what the Archdiocese has planned. The proposed new convention center would double what we already have. Maybe Santa Fe really is so different that it can fill all that space. But the disappointed cities cited in the Brookings report must have thought they were special too.

Santa Fe's hotels continue to attract annual meetings by professional groups like the Society for Applied Anthropology and the Western Orthopaedic Association, as well as smaller gatherings: the American College of Cardiology Colloquium on Cardiovascular Therapy, the Workshop on Performance and Productivity of Extreme-Scale Parallel Systems, the Forum for Motor Carrier General Counsels, the International Symposium on Liquid Metal Processing and Casting, the Human Cognitive Models in System Design Workshop . . . .

Maybe that is good enough. The consultants estimated that 57,600 people come here each year for conventions compared with a "peer market average" of 422,892. But do we really want anywhere near that many more people in town?

The most glaring omission in the consultants' report was a consideration of where the water would come from. Buckman? If construction costs are really rising by 2 to 3 percent a month, that means the price tag for the ever elusive Rio Grande diversion is increasing by as much as $4.8 million a month . . . $160,000 a day . . . $1.85 a second.

Standing on the steps of the post office looking across the empty wasteland, one can only wonder if the smart thing to do is not rebuild Sweeney. Put in a layer or two of underground parking and then some gravel and grama grass on top. The land isn't going anywhere. Save it for another day.

Coming Soon: The Battle for Talaya Hill

The Andrew and Sydney Davis Webcam

Santa Fe Review Detours of the Wild West

The Santa Fe Review

More links:

See the current flow of the Santa Fe River above McClure Reservoir with the USGS automated gauge.

The Otowi gauge shows the flow of the Rio Grande north of Santa Fe.

Santa Fe water information, a collection of documents and links