copyright 2005 by George Johnson

Lake Dillon, Colorado, photo by George Johnson

1. Retrofit Arithmetic (and Rainbarrel Economics)

2. The San Juan-Chama Shell Game

3. The Case of the Disappearing Aquifer

4. The Creative Hydrology of Suerte del Sur

5. The City, the County, and a Water Tax Revolt

6. Water Numerology at City Hall

7. The Woman at Otowi Gauge

8. "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."

9. The Las Campanas Connection . . . desalination word games . . . and Aamodt South

Our story thus far:

With its population growing by leaps and bounds, the once sleepy town of Santa Fe found itself running out of water. The annual rainfall, which had been anomalously high for several decades, began dropping back to normal levels, a phenomenon that came to be known as the drought. The watershed on the western slope of the Sangre de Cristo mountains was providing less water than it had in the recent past, and the Buckman well field by the Rio Grande was being pumped so hard that the water table had dropped by hundreds of feet. The result was a "cone of depression" sucking water from the neighboring aquifers in Tesuque and Pojoaque -- water the city would be compelled to pay back at great expense.

Faced with the situation, Santa Fe was forced to decrease consumption while trying to find a way to increase the supply. First, unwilling to place any limits on new construction, the city enacted rules and penalties designed to compel existing residents to use less water. To set an example, the city let its parks die, destroying untold thousands of dollars of public property -- the landscaping that had been paid for and maintained over the years with taxes. Meanwhile, with every drop of Santa Fe River water impounded in the Upper Canyon reservoirs, the bosque began to die.

For a while, Santa Feans took pride in achieving one of the lowest per capita rates of water consumption in the West. But as their city grew drier and uglier, while the building boom continued unabated, many began to complain. Some were even demanding a construction moratorium.

To head off the threat, the Council enacted the retrofit program. A builder could have all the building permits it wanted as long as it agreed to replace enough old water-guzzling plumbing fixtures to "entirely offset" (as the ordinance stated) the amount of water the new houses would consume. In practice, the number of required retrofits never came close to equalling the demand created by the new construction. As more residences and whole new subdivisions continued to appear, the water situation only grew worse.

Enter the Buckman Diversion plan -- a $120 million project, years behind schedule, to take Santa Fe's allotment of San Juan-Chama water directly from the Rio Grande instead of the Buckman well field. This wouldn't actually result in more water -- the same number of acre-feet would simply be drawn from a different source. But at least this would reduce the unsustainable pumping that had been keeping the city barely afloat.

There was just one problem: If the city began taking all of its San Juan-Chama water from the river, there would be none left to trickle down and restore the aquifer -- returning the water it had been "borrowing" all these years. So, just to break even, the city had to agree to lease water from the Jicarilla Apache reservation at a cost that could reach a quarter billion dollars over 50 years -- all just to maintain the shaky status quo.

Meanwhile, it was business as usual for the real estate speculators. "Toilet brokers" went door to door offering free retrofits, then selling the credits to developers. South of town, in the county, Rancho Viejo began building what is projected to become a 10,600-acre city (half the size of present-day Santa Fe), stretching from Richards Avenue to join up with Eldorado.

Something had to give. Santa Fe had to either find a way to control its growth, or bring in a lot more water. And so it began casting its eyes to the north . . .

November 24, 2004

7. The Woman at Otowi Gauge

One of the classics of New Mexico literature, Peggy Pond Church's The House at Otowi Bridge, tells the story of Edith Warner, a frail, introspective young Easterner who came to live where the road to Los Alamos, now New Mexico Highway 502, crosses the Rio Grande at San Ildefonso Pueblo.

In those days the Chili Line (spelled in the original Texan) ran north from Santa Fe along the east side of the river bank. It passed the settlement of Buckman, headquarters  for a lumber operation that clear-cut Ponderosas from the Pajarito plateau. From there the train continued to Otowi Crossing on its way to Española and finally Antonito, Colorado. One of Miss Warner's jobs was to drop off and retrieve the mail bags. (More famously she ran a tea house whose guests included such illustrious Manhattan Project scientists as Robert Oppenheimer and Niels Bohr.)

for a lumber operation that clear-cut Ponderosas from the Pajarito plateau. From there the train continued to Otowi Crossing on its way to Española and finally Antonito, Colorado. One of Miss Warner's jobs was to drop off and retrieve the mail bags. (More famously she ran a tea house whose guests included such illustrious Manhattan Project scientists as Robert Oppenheimer and Niels Bohr.)

The railroad and the lumber town are gone now. Buckman is known only as the approximate location of the Buckman well field, Santa Fe's primary source of drinking water, and Edith Warner's old home site is the location of the all-important Otowi gauge. According to the Rio Grande Compact signed in 1939 to keep the state of New Mexico from sucking the river dry, a certain percentage of the water measured at Otowi must be delivered to Elephant Butte Reservoir, two hundred miles south, and ultimately to the Texas border.

Suppose that Santa Fe, or perhaps Rancho Viejo, wanted to buy water rights, 1,000 acre-feet or so, from the northern Rio Grande and transfer them for use downstream. The Otowi gauge would present an obstacle. Since the water would no longer be consumed north of the bridge, the flow measured by the gauge would increase -- and so would the amount of water New Mexico was obliged to deliver to Texas.

But long before the water reached Elephant Butte, it would be sucked into the municipal water system, removed from the river. Unless Texas and Colorado (the other signatory to the agreement) could be persuaded to renegotiate the terms of the compact, approving a transfer of water rights across the Otowi gauge would be a net loss to New Mexico. Thus the State Engineer has long had a policy of summarily rejecting any such requests.

Consequently, though this was not the intent, the gauge serves as a kind of membrane, protecting the rural quality of northern New Mexico. Santa Fe developers would like nothing better than to get their hands on those thousands of acre-feet used by the acequia associations to water their Velarde apples and Chimayo chiles. Dollars would flow north, water rights would flow south, and as an added bonus all those fallow fields and dead orchards would be good for -- what else? -- building more subdivisions. Without the Otowi gauge, the Santa Fe Farmer's Market might have little on its tables but sandalwood incense and macrame candle holders.

So, given that the city and county have shown no willingness to curb their voracious growth, where do they plan to get more water? One solution would be to lease still more San Juan-Chama rights, as has already been done at great cost from the Jicarillas. Since this is not native Rio Grande water (but is imported from another basin) it is not counted in the Otowi calculations.

Altogether there are more than 3,000 acre-feet of San Juan-Chama water rights owned by Rio Grande communities north of Santa Fe. (Here is the chart again.) Conceivably some of this paper water might someday come up for grabs. But considering how jealously norteños guard their independence, that seems like a long shot. In any case, the price is guaranteed to be sky high.

More likely, Santa Fe's boosters are pinning their hopes on a better bet: the outcome of the convoluted, decades-long legal case formally known as State Engineer vs. R. Lee Aamodt et. al. Despite the impression you might get from the local newspapers, Aamodt is about far more than Indian golf courses and Tesuque wells. We'll see why in the next installment.

November 29, 2004

8. "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."

When State Engineer Steve Reynolds filed the Aamodt suit, his intent was to settle, once and for all, who owned the water in the Pojoaque and Tesuque basins, just north of Santa Fe. How much could the pueblo Indians, the original inhabitants, claim, and how much did they have to leave for their neighbors, the Hispanic and Anglo settlers who have come to depend on the streams and aquifers?

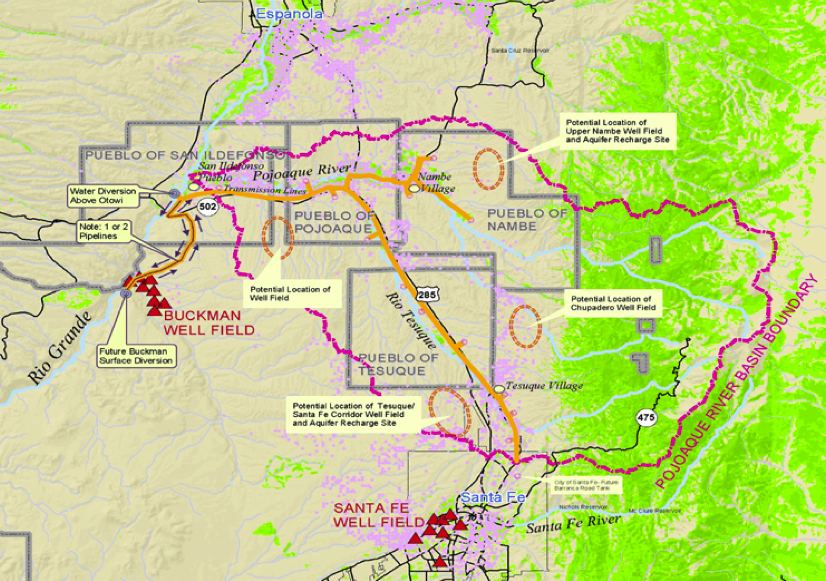

That was 38 years ago. Three judges and four State Engineers later, the litigation continues, making it the longest-running case in the federal court system. In the meantime, the proposed solution has evolved into something Mr. Reynolds may not quite have envisioned: a grand plan for a "Pojoaque-Santa Fe Regional Water System" capable of delivering as much as 21,000 acre-feet a year.

The case is as convoluted as the plot of the movie "Chinatown," but what it comes down to is this: the pueblos claim a "first priority right" to consume about twice as much water as they are currently using. If they eventually want it all -- for, say, more golf courses and resorts like at Pojoaque pueblo -- there would be little or no water left for anybody else. In times of drought, the Indians might even issue a "priority call," demanding that non-Indians stop irrigating until the pueblos have satisfied their own demands.

Earlier this year, the lawyers for all the parties proposed a settlement agreement. The centerpiece is a federally funded system that would draw water from the Rio Grande and distribute it throughout the region. The Hispanos and Anglos would cap their wells. In return, the pueblos would agree to some limits on their right to make priority calls. (As a sweetener, Washington would buy them more water rights.)

Those are the bare bones of the deal. The details, spelled out in the 65-page document, are as complex as they are controversial and have been described by the local papers. What has received surprisingly little attention is Section 2.1.5 of the proposal:

Pursuant to a written agreement and subject to the terms of this Agreement, a Pueblo may lease, for any term up to 99 years, any portion of its First Priority Rights for use within the area served by the Regional Water System to (a) another Pueblo . . . or (b) another water user. . . .

Who all would be included in "the area served by the Regional Water System?" Both the Pojoaque and the Santa Fe River basins. Furthermore the agreement would be administered by a Regional Water Authority consisting of the pueblos and both the county and city of Santa Fe "for the purpose of ensuring a reliable firm supply of water to all users" [my italics].

The additional water rights the federal government promises to buy for the Indians could also be used "for any purpose, including uses off that Pueblo's lands" and leased to others "for any term up to 99 years" [Section 2.5.1-2]. The same goes for any water rights the pueblos might buy on the open market.

What this seems to suggest is a mechanism for the pueblos to become net water exporters, selling to Santa Fe the additional acre-feet it needs for more development. Since the intake for the system would be at San Ildefonso pueblo, just north of the Otowi gauge, the Rio Grande Compact would present no obstacles. As long as upper Rio Grande water is diverted above the gauge, it can be consumed anywhere without affecting New Mexico's obligations to Texas.

All that is lacking would be a means of physically transporting the water from San Ildefonso to Santa Fe. Alternative 4 of a "feasibility study report," prepared last fall by the Bureau of Reclamation, describes a scenario in which an additional pipeline would be built from the San Ildefonso intake to the future Buckman Diversion Dam -- a distance of only four miles. The capacity of the line, 15,000 acre-feet, would potentially double Santa Fe's (city and county) water supply.

Here is a diagram from the report:

Also mentioned is the possibility of a smaller, parallel line to transfer lower Rio Grande water for use by the pueblos and municipalities above the gauge. The Otowi membrane would be breeched and all kinds of deals would be possible.

None of this may come to pass -- there is still no signed agreement. All the caveats about paper water versus wet water still apply. But it is hard to look at that map and the proximity of Buckman to San Ildefonso without hearing the sound of rushing water, and the damnable beeping of backhoes.

December 3, 2004

The New Mexican and Journal North are both fine newspapers, far better than a town this size has any reason to expect. The competition to cover the news enhances the quality of local journalism.

But this morning's reports demonstrate how important it is to read both papers for an adequate understanding of what is going on.

Here is the opening of the New Mexican's report on the approval yesterday by the city Planning Commission of another large new development on Cerrillos Road:

And here is the Journal:

According to the Journal story, the developer claims that the project, which will include a Lowe's home improvement center, a multiplex movie theater, and more than 60 acres of housing, will (because of the miracle of retrofitting and "aggressive water-conservation methods") use no new city water at all.

December 20, 2004

9. The Las Campanas Connection

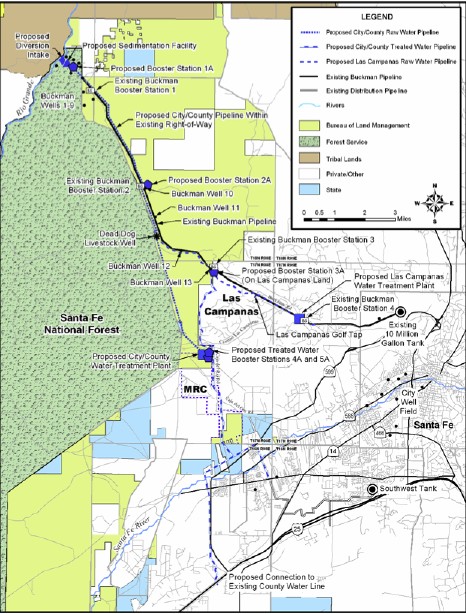

In 192 pages of charts and analysis, the draft environmental impact statement released last week for the Buckman diversion project comes to the same conclusion that has been reported in these pages: After the dam has been built and the pipes have been laid, there still will not be any new water for the City of Santa Fe. The 5,230 acre-feet it is now taking each year from the Buckman well field will simply come directly from the river instead.

The county might get more water -- 1,700 acre-feet a year, if it can buy and transfer additional water rights. (According to the report, it would need another 1,254 acre-feet.) How the water will be used will depend on the political will of the County Commission. Either it will go to serve existing residents -- reducing the number of straws in the aquifer -- or, more likely, for more development.

What hadn't occurred to me until yesterday, when I read the report, is that the biggest winner will be Las Campanas. (Remember that through an arrangement with the city, it gets its water from the Buckman well field.) Without the diversion project, the development would be limited to its current size. The diversion dam will allow it to take all the water from the river it needs for "full build-out," more than quadrupling from 410 to 1,717 luxury houses. It already has the rights, 1,800 acre-feet. It just needs a mechanism to deliver them.

The report (which can be downloaded here), is well written and makes for fascinating reading. (O.K., I skipped the parts about the environmental impact on the Flathead chub and the Loggerhead shrike).

The National Environmental Protection Act requires that these studies also examine a "no action" alternative -- what would happen if the project was not built. What is striking is how little it differs from the action alternative. Even if the diversion is running at maximum capacity, 8,730 acre-feet a year, it won't provide nearly enough water for ambitious plans like Rancho Viejo and the development of the Northwest Corridor. If these come to pass, it is hard to see where the water will come from -- except from above the Otowi gauge and at the expense of Northern New Mexico agriculture.

December 24, 2004

. . . Or, so it suddenly seems, from the Estancia Basin south of Albuquerque. Yesterday Mayor Larry Delgado dropped a bombshell when he announced that he and the city council have been secretly dealing with a recently incorporated company, Sierra Water Works, which controls 7,200 acre-feet of rights to what is often described as an underground sea -- a table of brackish water that would have to be run through a desalination plant before being pumped about 65 miles uphill to Santa Fe. Both the New Mexican and the Journal describe the details in today's papers and note that similar schemes in the past have met with substantial opposition from Estancia-area ranchers and the State Engineer. The fear is that overpumping would damage an already overburdened aquifer, depleting existing wells and drawing salt water into the area's fresh-water drinking supplies.

Clearly this would be an expensive endeavor. If the Council approves the deal, it will cost the city a total of $27 million upfront. That doesn't include building the desalination plant and the pipeline, estimated at $100 million. In addition there would be the substantial energy costs of pumping water up the 1,000-foot incline separating Torrance County and northern New Mexico. As usual, the city plans to look to the Federal government for some of the money. The rest would be paid by increases in taxes and water rates.

Already faced with footing the expense of the Buckman diversion and the Jicarilla deal, why would residents wish to take on this additional cost of living in Santa Fe? City officials told the Journal that the extra water would allow our own well fields to rest. But that was supposed to be the reason for the Buckman project. Mayor Delgado provided the real answer in the form of a rhetorical question: "How can we talk about annexation and development when we don't have the water?"

More on this after the holidays.

December 29, 2004

Despite the holiday lull, the Journal continues to go after the Estancia water grab: a piece yesterday confirms just how strong the opposition will be in Torrance County, and a story today raises the possibility that, with a pipeline and desalination plant in place, more local farmers will line up to sell their own brackish water to Santa Fe. The great invisible hand of the marketplace could result in a bumper crop of salt water edging out hay and cattle as the county's chief agricultural export.

Meanwhile, the New Mexican chimes in this morning with an editorial suggesting just why the plan may be as unpopular with Santa Feans as with Estancia Basin farmers:

If the Estancia stunt is carried off, city folks can count on higher taxes and higher water rates to pay for it; all for the sake of growth and the higher taxes it brings. Also boosting beyond-city-limits sprawl would be City Hall's notion that the huge Rancho Viejo development to our south and Eldorado to its east might like to share in the Estancia scheme's cost. Buying into the project could shore up supplies for the vast suburbia so long a twinkle in developers' eyes.

With a new pipeline paralleling Highway 41, perhaps Edgewood, Moriarty, Stanley, Galisteo, and Lamy can all look forward to becoming engulfed by the Greater Santa Fe-Albuquerque Metropolitan Area.

December 31, 2004

There are two reasons why the word "desalination" is associated in most people's minds with Saudi Arabia: the country's proximity to the ocean and its seemingly bottomless supply of money and oil. Desalination is a very expensive, energy-intensive technology, one that you rely on only when there is no other choice.

Faced with a rapidly shrinking aquifer, another seaside kingdom, the Tampa-St. Petersburg metroplex, decided to build a desalination plant in what seemed like an ideal location -- adjacent to a power plant on Tampa Bay. After a couple of bankruptcies, a lawsuit, and tens of millions of dollars in cost overruns, the project is at least four years behind schedule. (See "$29-million more going to troubled desal plant," St. Petersburg Times, November 16, 2004.)

Inland desalination of groundwater might be an even bigger gamble. The water may be less salty and easier to treat, as promoters of the Estancia Basin plan have told the newspapers this week. (There is a particularly optimistic assessment from a hydrologist in today's New Mexican.) But the landlocked location raises additional obstacles. Desalination produces toxic waste in the form of brine -- concentrated saltwater. Coastal plants can simply dump it back into the ocean. In places like the Estancia Basin, the waste must be handled in a way that doesn't contaminate the aquifer and kill flora and fauna. We won't really know how expensive this water will be until someone comes up with an estimate of annual operating costs, including waste disposal and energy consumption, as well as legal fees for fighting claims by farmers who say their wells have been contaminated or dried up. Meanwhile Sierra Water Works is pushing Santa Fe for a quick decision. (The company would pocket a $2 million down payment on a purchase option even if the project collapses within a year.)

Last year, a report by Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque and the federal Bureau of Reclamation, "Desalination and Water Purification Technology Roadmap," concluded that the technology was not yet ready for places with the resources of Santa Fe:

Current-generation desalination plants are expensive to buy and operate, and thus cannot produce water at rates that are affordable for agricultural uses or for municipal use in small and medium-sized cities. Thus, the nation's agricultural heartland will need new, next-generation desalination technologies capable of producing less expensive water. [page 23, my italics]

Or perhaps the determination to encourage an economy not dependent on real estate speculation and limitless population growth.

January 4, 2005

Word Games

The Estancia Basin saga continues this week with Sierra Waterworks arguing semantics: Though the water it wants to sell is indeed salty, undrinkable, and, we learn today in The New Mexican, tainted with sulfur, it is not "brackish." Merriam Webster disagrees. It defines the word as

1. somewhat salty 2. not appealing to the taste

And the Sandia/BLM study mentioned here in an earlier installment says brackish means "containing higher TDS [total dissolved solids] than potable water, but lower TDS levels than seawater."

Just as questionable is the company's contention that selling the water to Santa Fe, instead of using it to irrigate crops, will result in half the amount of pumping and therefore half the amount of water being removed from the basin. Here is the reasoning: Under New Mexico law farmers can pump much more from the aquifer than they actually own, the theory being that much of the water will trickle back into the ground. The water you are allowed to deplete, your "consumptive rights," is supplemented by borrowed "nonconsumptive" water. Only the consumptive rights, of course, can be sold and exported.

But if all that borrowed water really has been returning to the earth -- if there is a scientific basis for the law -- then it should make no difference whether the consumptive water is sold elsewhere or used onsite for agriculture. Either way there would be precisely the same amount of depletion.

A more pertinent issue is whether the technology to treat this kind of water is affordable and ready for prime time. A paper on the New Mexico Water Resources Research Institute's web site, "Desalination of Inland Brackish Water: Issues and Concerns," estimates that the process is now only 60 to 85 percent efficient. "Unfortunately this means that 15 to 40 percent of the available water is not used and often must be disposed, wasting potentially valuable water resources and requiring additional pumping." And while coastal desalination of seawater can be done for $2.00 to $2.50 per 1,000 gallons, inland desalination "may cost twice as much . . . because of smaller plant sizes, higher concentrate disposal costs, higher water pumping costs, and higher energy costs."

That's presumably on top of the cost of purchasing the water. Without doing more research, Santa Fe is faced with the possibility of spending $27 million for rights to water that it can't afford to use. It would also get a 51 percent interest in 8,702 acres of Torrance County farmland. If worse came to worse, maybe it could take up alfalfa farming.

January 13, 2005

Aamodt South

Yesterday was a singularly bad one for Santa Fe's ambitions to subsidize more growth with imported water. First came the announcement that, no, actually the federal government is not willing to pick up most of the cost of the regional water system that has been touted for months as the solution to the endless Aamodt litigation. (Though the newspapers rarely report this, the project would include a pipeline leading from the upper Rio Grande, around the Otowi gauge, and directly into Santa Fe's water mains at Buckman.)

While this shock was being absorbed, residents of both the Estancia Basin and Santa Fe flocked to a city council meeting to denounce a scheme to pipe in desalinated water from the south. With the mayors of both Estancia and Moriarty and other Torrance County politicians vowing to block the deal, we may soon see another Aamodt-style case on our southern flank: protracted legal wrangling that could be tied up in the courts for many years to come.

The Estancia proposal has already developed into a public-relations disaster. It turns out that only half the 7,200 acre-feet offered by Sierra Waterworks has been verified by the state engineer. And, as uncovered by Journal North, Santa Fe's water director, Galen Buller, previously worked as a lawyer representing John Cyle Sharp, the president of Sierra Waterworks, in his efforts to secure the very water he is now trying to sell. This may not be a serious conflict-of-interest, but it adds to a growing sentiment that the plan is, as Neva van Peski, a critic of local water policy, put it at last night's hearing, "a classic sucker's deal."

The only Santa Feans speaking in favor of the plan at public forums have been lawyer/entrepreneur Earl Potter and Gary Ehlert, president of the Santa Fe Area Homebuilders Association. He balked, however, at a suggestion that the imported water be paid for by those who would most benefit -- developers -- through higher utility expansion fees.

The Santa Fe Review

More links:

Santa Fe water information, a collection of documents and links