copyright 2009 by George Johnson

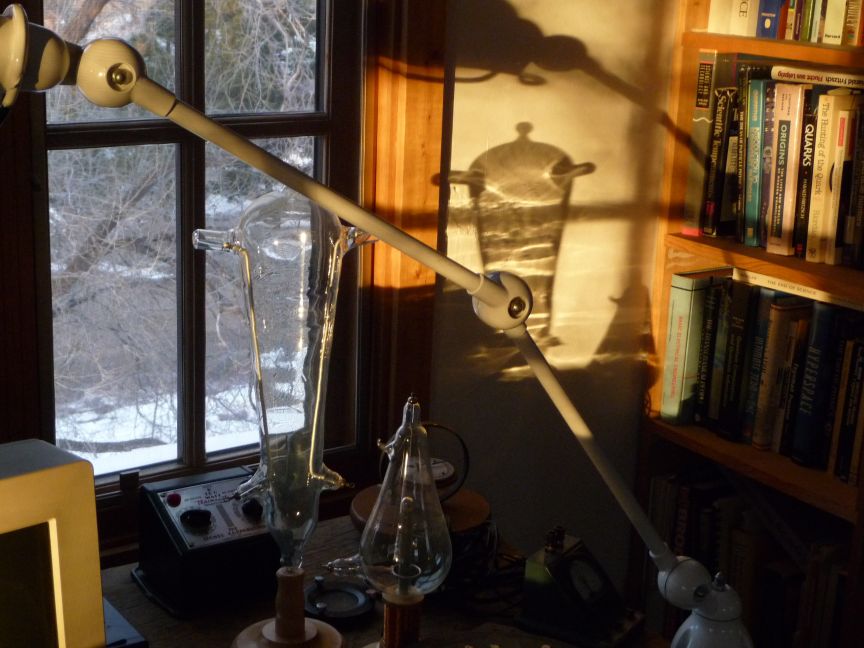

My office, January 4, 2009. photos by George Johnson, copyright 2009

1. Retrofit Arithmetic (and Rainbarrel Economics)

2. The San Juan-Chama Shell Game

3. The Case of the Disappearing Aquifer

4. The Creative Hydrology of Suerte del Sur

5. The City, the County, and a Water Tax Revolt

6. Water Numerology at City Hall

(Our story thus far)

7. The Woman at Otowi Gauge

8. "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."

9. The Las Campanas Connection

(Our story continues)

10. The Engineering Solution

January 4, 2009

57. My Anti-blog

Looking at the creation dates of some old files on my computer, I realized this morning that it has been 14 years since I started writing things and putting them on the Internet. Four years later, in March 1999, I decided to call my personal website talaya.net after a mountain on Santa Fe's eastern edge. If the word "blog," a portmanteau of "web log," existed back then I hadn't heard it. I first came across the term a year and a half later in an article by Rebecca Meade in The New Yorker about a subculture of young adults with nicknames like Megnut and Evhead who were posting personal diaries -- blogging -- on the web.

Since then the blogosphere has expanded exponentially with an estimated 26.4 million bloggers in the United States and 184 million world wide. A. J. Liebling once wrote that freedom of the press is limited to those who own one. That's no longer a problem. It costs nothing to self-publish your opinions on the Internet. You might even make a little money by running Google ads. The competition is fierce. To survive you must post as quickly and as often as possible. You stumble upon a scrap of information -- a couple of sentences or a YouTube clip -- and you blog it, providing a link and your gut-level response, the more opinionated the better. As a how-to article on Slate put it, "Don't worry if your posts suck a little."

The result, my colleague Charles Seife recently wrote, is a "Malthusian information famine":

There are some hundred million blogs, and the number is roughly doubling every year. The vast majority are unreadable. . . . There seems to be a Malthusian principle at work: information grows exponentially, but useful information grows only linearly. Noise will drown out signal. The moment that we, as a species, finally have the memory to store our every thought, etch our every experience into a digital medium, it will be hard to avoid slipping into a Borgesian nightmare where we are engulfed by our own mental refuse.

Now that is good writing. The higher quality information -- the signal -- is produced by people who slow down and reflect. They translate their thoughts into words, build words into sentences, sentences into paragraphs, and paragraphs into essays. They are not blogging, they are writing -- crafting prose that happens to be published electronically as all prose inevitably will be.

Since 2004, when I started The Santa Fe Review, I've gotten used to being called a blogger, sometimes by people who complain that my blog is upside down: with the old stuff on top and the new stuff on the bottom. But that is how journals are written and how they are read. I don't expect many new readers will start way back at the beginning, but at least they can read a few posts sequentially and see the titles of what came before. That way there is a context and a history.

The blogosphere, with all its excitement, is stuck in the present tense, layered anew each day, each hour, each minute on top of its buried past. With effort you can drill through the strata. You can read upside down. More likely you'll be tugged by a link to a new spot on the surface, and then another and another and never get in deep.

I've experimented offline with blogging software like WordPress, which would make the Santa Fe Review look something like this. I could post easier and faster though I'd miss the satisfaction of hand coding each page. I'd have things called permalinks and pingbacks so bloggers worldwide could comment on my comments. People with made-up names could anonymously post their reactions, driving more traffic to my site. But I don't want hits, I want readers.

In that New Yorker article from November 2000, Megnut and Evhead were just starting blogger.com ("push-button publishing") to make it easy for anybody to get online. Later their company was purchased by Google. A rival, Windows Live Spaces, is owned by Microsoft. MySpace is part of Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation. This is the dirty little secret of blogging: It's the media corporations that have been making the money by persuading millions of people to provide content for free.

That is not likely to last in this economy. But as the blogosphere shrinks, the best stuff will endure. At some point, when the novelty of electronic writing has worn off completely, people will stop calling it blogging. Peeled from its paper backing, good journalism will only get better. More panoptic and responsive, drawing on a widening range of information, it will be something worth paying for.

January 6, 2009

The Sunday New Mexican ushered in the New Year with its smallest real estate section yet -- eight pages. Since the heyday of the housing boom, Rancho Viejo's weekly advertisement had already shrunk from a two-page spread to a single page to half a page on the cover. Last month it was dropped altogether. This week Prudential is gone too and, more significantly, real estate giant Santa Fe Properties. Even filling what is left of the section (which is now in one part instead of two) was a strain for the ad department, requiring a 2/3-page house ad pointing out the virtues of classified advertising in the New Mexican.

Hoping maybe to stoke the fires, the newspaper's business editor, Bob Quick, reports today that there has been a "surge in applications" for mortgages, though mostly refinances. You have to read down to the fifth paragraph to see what counts as a surge these days. A lender at Century Bank says the market remains not just slow but "the slowest I've seen."

Though there is a record number of unsold houses (in realty speak this is called "inventory"), the median house price actually rose a bit last quarter. This is not some bizarre distortion of the laws of supply-and-demand. As realtor Karen Walker pointed out in Mr. Quick's business column, million-dollar properties have been easier to sell than those in the $300,000 to $500,000 range. Apparently there are enough rich people who remain rich enough after the financial collapse to go bargain hunting for trophy houses.

I suspect that the days are long gone when half a million dollars or even $300,000 is considered a reasonable price for a modest home. When, at the height of the frenzy, a realtor friend estimated that my house was worth triple what I'd paid in 1993, I should have sensed that the whole economy was on the brink and sold every stock I had.

January 11, 2009

2020 Hindsight

Last month just after returning from Spain (where, on the outskirts of our sister city, Santa Fe de Granada, I learned what happens if you accidentally put gasoline in the tank of a rented diesel car), I found myself at a table with two former city managers, Asenath Kepler and Isaac Pino, who is now president of Suncor New Mexico, the developer of Rancho Viejo. The occasion was the first Santa Fe Neighborhood Law Center Conference, organized by attorneys Fred Rowe and Dan Yohalem, and we were supposed to discuss "Laws and Planning Policies for Diverse 2020 Santa Fe Neighborhoods."

As the moderator, Ms. Kepler asked smart, stimulating questions: Can a tension between the historic past and the promising future act as our gateway to creative urban planning and design? Can the city's legendary creativity give rise to an integrated system of distinct and diverse neighborhoods that are environmentally sustainable in the emerging green economy? Finally, she asked that we consider "the vision of Santa Fe as a new model of urbanism" (not necessarily, she quickly added, "a model of new urbanism"). "What should we look like in 2020?"

Damned if I know. In his column this week, Zane Fischer complains that Mr. Pino and I weren't up to the challenge, falling into our default modes of pro- and anti-development. I can't speak for Ike, but I think the problem ran deeper. As a recovering Aquarian, I cringe when I hear words like "sustainability," "green," and even "diversity." Since entering the lexicon about the time I was in college, the words have been stripped of their meaning and co-opted. Like "affordable housing" and "infill development," they have become incantations used by developers to charm city leaders into approving the next master plan.

I'm sure Ms. Kepler was speaking in the old idealistic way. But I couldn't help feeling as though we'd fallen into a time warp. With the undoing of the economy, questions that would have had traction a few years ago have become almost beside the point.

With almost 800 residences priced under $300,000 languishing on the market, do we need to be designing whole new neighborhoods of moderately priced homes? If we really wanted to be creative, we could expand award-winning programs like Homewise with the aim of rehabilitating existing housing stock and helping people buy what is already on the ground.

If the Obama administration makes good on its promise to launch a second New Deal with something like FDR's Civilian Conservation Corp focused on energy, there may indeed be an "emerging green economy." Some financial analysts are already predicting that this, after the Internet and real estate, will be the next bubble. Get in while you can.

But the notion of a sustainable Santa Fe is an anachronism. Whatever opportunity there may have been vanished decades ago when the city outgrew its aquifer and its river and responded by colonizing the Buckman well field. Now we've destroyed Buckman so we are trucking in massive amounts of concrete and steel to build the Rio Grande Diversion Dam and an energy-guzzling filtration plant. We're seeking water rights from as far south as Socorro and considering the possibility of building megawatt desalination factories to import ancient seawater from Eastern and Southern New Mexico.

I was still pretty jet-lagged during the panel discussion and worrying that I might find a charge from Avis on my Visa card for the price of a replacement Audi engine. But I think I made the point that Santa Fe has sometimes suffered from too much creativity, especially when it comes to language. Builders construct new office complexes while old ones sit vacant and then congratulate themselves on using "green" materials. Developers plat suburbs as dense as anything at Rio Rancho, on Albuquerque's West Mesa, and call them "villages."

This is sounding more pessimistic than I feel. I'm encouraged about the arrival of the Railrunner and the Railyard development -- publicly funded projects that might open the way for renewal. With one eye on Obama, I've started reading the second volume of Schlesinger's Age of Roosevelt, hopeful about the possibilities of government by people not bound by the market, and who have a reckless insistence on saying what they really mean.

January 23, 2009

Ecovoyeurism

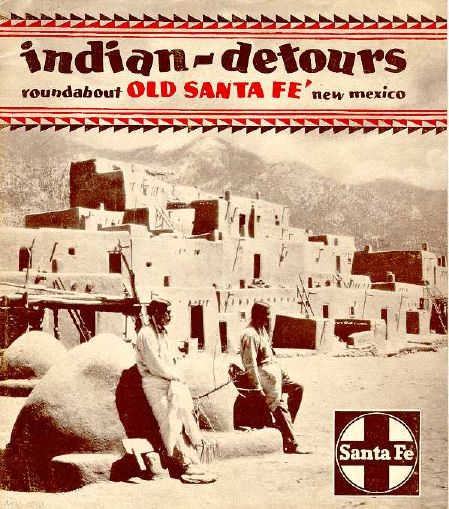

In 1925 Fred Harvey established his legendary Indian Detours, offering adventurous tourists motorcar excursions "Off the Beaten Path in the Great Southwest." A brochure from those days describes the offerings:

What Harvey was promoting so many years ago has been rebranded "ecotourism," which can be added to our earlier list of words (like "green" and "sustainable") that have been hollowed of meaning and embraced by the public relations industry.

Last week the New Mexico Department of Tourism staged a news conference at the Inn and Spa of Loretto, with hired Native American dancers, to announce plans for a new $500,000 "ecotourism division" headed by Deputy Tourism Secretary Jennifer Hoffman. Before receiving her call to public service, Ms. Hoffman, Tom Sharpe reported in the New Mexican, worked for a Los Angeles company, Ballantine PR, which organized the event at Loretto and, incidentally, donated $9,450 to Governor Richardson's presidential campaign.

According to Ms. Hoffman, ecotourism is "travel that preserves the environment and improves the conditions of the people who live there":

They are, in other words, the same people who have been coming here all along. Now they deplane in Albuquerque instead of detraining at Lamy. As Karen Peterson suggested in an editorial in Wednesday's Journal, the $500,000 requested for ecotourism will probably buy nothing more than "another boatload of consultants."

There are more meaningful ways to spend the money. Northern New Mexico has the beauty and depth of Provence, Tuscany, or Andalucia. But something has always been missing: the good inns and restaurants one finds in the smallest southern European villages. Imagine if almost every town along the High and Low Roads to Taos, between Las Vegas and Peñasco, between Abiquiui and Ojo Caliente, and between Tierra Amarilla and Tres Piedras, had locally owned lodging with expertly prepared meals made from the same fresh produce that is now carried to Santa Fe for sale at the Farmer's Market.

In Europe a loose network of these way stations emerged naturally as part of a long history of commerce. Developing a similar economy in New Mexico would require a jumpstart. The state's wish list for Obama's New Deal could include money for a Northern New Mexico Culinary and Hospitality Institute to train local chefs and innkeepers and provide consultation and low-interest start-up loans. As the seeds sprouted, unemployment, poverty, and maybe even heroin addiction might subside. Towns like Truchas and Abiquiu, with a long-standing distrust of outsiders, might crack open their doors if tourism was reconfigured so that it really was to the benefit of the locals.

What prevail instead are corporate simulations. Last week I stayed one night at the Hyatt Regency Tamaya Resort & Spa at Santa Ana Pueblo to give a talk at a conference called Decade of the Mind. The staff was friendly and the view of Sandia Mountain was magnificent. From that angle you can really see why some of the pueblos call it Turtle Mountain. Between sessions I enjoyed a walk through the bosque to the Rio Grande. But overall the experience was managed and fake, from the sappy Kokopelli flute muzak in the lobby to the designer pueblo decor.

At the hotel restaurant (called Corn Maiden, signifying "the special relationship between the farmer and the plant"), guests could start with "Foie Gras Truffle-Scented Crème Brulee" or "Buffalo Rib Eye Carpaccio" before moving on to a rotisserie of "Chorizo Sausage, Fresno Chile Chicken, Rose-Salted Beef Rib Eye, and Lavender-Salted Shrimp" with a side of "Green Chile Potato Au Gratin in Cocotteen." I longed for a Frito pie.

I left the conference hoping that none of the scientists who had flown in from afar would go home believing that Tamaya had anything to do with New Mexico.

January 25, 2009

Suddenly Affordable Housing

In a thoughtful column in this morning's Journal, Karen Peterson questions

something I wrote here on January 11:

Actually I said that there are "almost 800" in the Santa Fe metro area. I got the same figure this morning from realtor.com by searching within 20 miles of the city limits.

Ms. Peterson is right that this number is top-heavy with condos -- and that a lot of these are too small for more than one or two people. But if you specify a minimum of two bedrooms, the search engine still coughs up 671 properties. Some of them look pretty junky. But the selection of unsold residences is only going to increase while prices continue to fall. (Demand is so slight that this week's New Mexican real estate section has shed yet another two pages with only one of the big three realtors, Sotheby's, still running a display ad.)

Along with all the surplus houses, hundreds of thousands of square feet of abandoned commercial property is being dumped onto the market. At a "smart growth" conference last week in Albuquerque, Arthur C. Nelson, director of metropolitan research at the University of Utah, predicted that much of this vacant space will inevitably be revamped into housing. "The dead mall is our future," he said. "Embrace it." That may sound grim (more "live/work lofts" on Cerrillos Road) but it is not only big box stores that are going under.

As Heather Clark reported in the Associated Press, an increasing number of aging baby boomers are expected to trade their houses for smaller quarters freeing up even more real estate. The financial contraction will only accelerate that trend.

"We are at the cusp of a fundamental change in the housing dynamics in this country, and we're not aware of it," Dr. Nelson said. That is what makes me worry that the City of Santa Fe is in too much of a hurry to develop all that empty land in the Northwest Quadrant.

February 1, 2009

The New Mexican's environmental reporter, Staci Matlock, has been on a roll with one fine story after another: a package of articles on wind power published January 11 was followed two weeks later by a fascinating report on the difficult science of mapping aquifers and the movement of underground water. Last week she described how developers are rushing to exploit a loophole in New Mexico law that leaves deep pockets of ancient seawater all but unregulated.

Until recently the briny deposits were considered little more than nuisances to be dealt with by energy companies drilling for oil and gas. But with the Southwest gripped by drought, entrepreneurs are hoping to profit by desalinating brackish water and pumping it as far as Phoenix, Tucson, and Los Angeles.

Fearing that the state legislature will finally clamp down on New Mexico's last supply of unappropriated water (don't hold your breath), companies are rushing to get in under the wire. Last Monday, Ms. Matlock reported, five limited-liability corporations (which under New Mexico law don't have to disclose whom they represent) informed the state engineer that they intend to pump 24 billion gallons of salt water a year from the Santa Fe area. Under the current law there is almost nothing he can do about it.

This issue arose here four years ago when a company called Sierra Waterworks wanted to sell Estancia Basin saltwater to Santa Fe. (For more on the matter, please see Part 9 of the Santa Fe Review, beginning with my dispatch of 12/24/04.)

February 1, 2009

Unsustainability

The best stuff in the New Mexican's Sunday Opinions section tends to get buried, as happened this morning with a piece by Lindsey Grant, identified as a former deputy assistant secretary of state for environment and population and staff member of the National Security Council. (Since the newspaper's web editors neglected to include the piece in the online edition, I've scanned and posted it.)

Mr. Grant expands on some of the same points we made earlier on this page:

His point is illustrated by an adjacent op-ed piece by Ted Harrison, the president of Commonweal Conservancy, a nonprofit organization that, under the banner of "eco-friendly development," is proposing to build a dense "village" of 965 houses between Lamy and Galisteo.

Like other developers, Mr. Harrison objects to Santa Fe County's uncharacteristically bold attempt to put a temporary moratorium on new subdivisions while land-use codes are updated. His project, he says, is different. According to its website, Galisteo Basin Preserve will "directly connect people to the land they inhabit, respect the land and water resources of the region, and thoughtfully and visibly support the cultural and economic diversity of northern New Mexico." It would also add 2,000 more people to a remote and fragile region that would be better left alone.

The intent, Mr. Harrison has long insisted, is to conserve most of the 12,000-acre spread, an old cattle ranch, by concentrating development rights near the highway, avoiding a sprawl of ranchettes. When I drove out there this afternoon the section called Southern Crescent looked to me like a typical subdivision, offering three- to nine-acre lots. Many of them were marked "sold" but none have been built on. Higher up on a mesa, in New Moon Overlook, I spotted three or four mansions on 100-acre tracts. The village, I suspect, is another New Urbanist fantasy that will never get from blueprint to ground.

On the way back to Santa Fe I stopped in Eldorado to buy some groceries for dinner. It took about three decades before this development, a product of the American Realty and Petroleum Corporation, gained enough population to attract a few businesses: a small supermarket, a coffee shop, a Home Run takeout pizza, and more recently a Subway franchise and a video rental store. For most of their shopping, the 6,000 or so Eldoradans drive to Santa Fe. If the Village at Galisteo Preserve is ever built, its citizens will probably be doing the same.

February 13, 2009

Atomic Ed

Ed Grothus, a true American original and proprietor of the Black Hole in Los Alamos, died on Thursday. Raam Wong wrote a nice tribute in the Journal.

I met Mr. Grothus a few times while I was scrounging for electronic junk at his amazing emporium. During the Wen Ho Lee affair, I wrote about him in an essay for the Times. A few years later I was back at the Black Hole again and described the experience in The Ten Most Beautiful Experiments. I'm reprinting an excerpt in memory of a very interesting man.

On a Saturday morning in January, in search of the last piece of equipment I needed to persuade myself that electrons exist, I set out for "The Black Hole," a postapocalyptic junkyard ("Everything goes in and nothing comes out") just down the road from Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. Run by Edward B. Grothus, a former bomb maker and now aging peace activist, the warehouse -- converted from an old grocery store -- is packed floor to ceiling with oscilloscopes, signal generators, Geiger counters, vacuum pumps, centrifuges, ammeters, ohmmeters, voltmeters, cryogenic storage vessels, industrial furnaces, thermocouples, barometric gauges, transformers, typewriters, ancient mechanical calculators -- more than 17,000 square feet of electronic and mechanical detritus cast off over the years by the national laboratory where the Manhattan Project began.

Over the years I had acquired on eBay most of what I'd need to repeat the classic experiments: J. J. Thomson's 1897 demonstration that electricity is a form of negatively charged matter, followed thirteen years later by Robert Millikan's triumphal oil-drop experiment, isolating and measuring the charge of individual electrons. Combing the dark aisles of the Black Hole, I finally spotted what I'd been looking for: a Fluke 415B High Voltage Power Supply. Reaching over my head, I carefully freed the long, gray chassis from the middle of a stack -- it weighed thirty pounds -- an lowered it to the concrete floor. Built in the 1960s and operated by vacuum tubes, it appeared to be in perfect condition. Dragging it to the back of the store, where miles of coaxial cables hung snakelike from hooks or lay coiled on the floor, I found one that fit the output connector and made my way to the cash register.

Ed never seems to actually want to sell anything. He'd rather tell you about his plan to erect a pair of granite obelisks to surprise alien archeologists after the coming holocaust, or about his First Church of High Technology, where he performs a "Critical Mass" on Sundays. By the time some customers tracked him down in the depths of his lair, he was in a cantankerous mood. "Two hundred fifty dollars for that," he said, about ten times what I'd been expecting. I tried to reason with him. There was one exactly like it on eBay for $99. But Ed is not a man to bargain. Disappointed, I dragged the unit back to its resting place, where it is probably still sitting, and left with just the cable. Stopping at the public library, next to Fuller Lodge, where Oppenheimer and the other nuclear physicists dined and partied, I signed on to the Internet and bought the other power supply. Two weeks later it arrived and I was ready to begin . . .

February 16, 2009

Though their lawyer, Tom Simons, pretended otherwise, his clients suffered a big blow last month when a district court judge upheld the city's right to regulate vacation rentals in residential neighborhoods. The only bone the judge threw to The Management Group, Kokopelli Property Management, and other agencies suing to overturn the law was an order that the city justify the $1,000 a year it charges for a short-term rental permit. Unless every penny is spent to implement the ordinance, the judge ruled, the fee is too high. Though Mr. Simons lost on every other point, he hailed his one tiny victory as "a significant decision in our favor." The city, happy to oblige, quickly vowed to adjust the price -- presumably downward -- and possibly refund some of the supposed overcharge.

In Sunday's Journal, Karen Peterson suggests a better option: using any extra proceeds from permit sales to step up enforcement. While the city has issued approximately 300 permits, she notes, a website called vrbo.com (Vacation Rental By Owner) advertises 600 Santa Fe listings offering lodging by the night. Some, no doubt, are legal (short-term rentals are unregulated in the county, and inns in commercial districts are covered by different laws), but Ms. Peterson uncovered several violators in just the first two dozen listings. An out-of-state landlord in her own neighborhood, who is charging $400 a night for an authentic Santa Fe experience, said she refused to get a permit because she personally objected to the law. If so then both she and vrbo.com are subject to prosecution.

The city cannot justify lowering the cost of permits until it has hired adequate staff to regularly comb the online listings and take violators like these to court.

Money should also be spent to maintain a current database of registered vacation rentals on the city website. Last fall when I asked for this information, the Land Use Department acted as though it were top secret, requiring the filing of a written request with the City Clerk.

Now that the city has issued more than 300 of the 350 permits allowed by law, I've asked for an updated list and will post it here when it arrives.

A Special Report: The Mysterious Destruction of the Santa Fe Indian School

The Tom Ford Webcam (stolen July 7, 2008, back online July 17)

The Andrew and Sydney Davis Webcam

Who Owns the Plaza? (this may take a minute or so to load)

A Stroll Along Shirley Maclaine Boulevard

The Santa Fe Review

More links:

See the current flow of the Santa Fe River above McClure Reservoir

with

the USGS automated gauge.

The Otowi

gauge shows the flow of the Rio Grande north of Santa Fe.

Santa Fe water information, a collection of documents and links

Santa Fe de Granada

Heretofore this great region has been

practically inaccessible to train travelers.

Couriercar Indian-detours, however, now carry

that comfort and perfect service sought by the

discriminating traveler to its uttermost

corners -- to its primitive Mexican

settlements and old missions; to its inhabited

Indian pueblos and prehistoric ruins; to the

mountains, canyons and forests of the

Southwest's vast open ranges and Indian

reservations.

It's about bringing the type of travelers who are actually

interested in having an authentic, hands-on experience. They

don't want to be in a bus driving through the landscape; they

want to be there in the landscape viewing the wildlife, fly

fishing on the river, visiting with a potter who's been doing it

for generations, showing the area where they fire their pots.

In a recent posting on his santafereview.com Web site, city

observer George Johnson says that there are more than 800

properties for sale in Santa Fe County for $300,000 or less

-- by Santa Fe standards, affordable. Given that, Johnson

wonders, "do we need to be designing whole new neighborhoods

of moderately priced homes? . . . Money for more affordable

housing -- such as the revenue that would be generated by a

proposed new tax on the sale of high-end real estate, on the

ballot in March -- might [he argues] be better spent beefing

up programs that help people buy "existing housing stock," or

homes that are already on the ground.

"Sustainable growth" is an oxymoron, and in the long term so is

"smart growth." Growth eventually becomes a mathematical

absurdity in a finite space. Invoking the word "sustainable" does

not avoid the consequences of the effort to keep growing. Even

our present population will be in a water crisis if we are moving

into a serious, sustained drought.

Galisteo Basin Preserve

Compared to the going rates [Ms. Peterson wrote], the city's

$1,000 permit fee amounts to chump change to most people in

the vacation rental business. Moreover, the goal of the new

law was to protect residential neighborhoods from further

erosion by commercial uses, including short-term rentals . . .

Rather than reduce the fee, the city should be prepared to

spend it -- by stepping up enforcement efforts.