copyright 2008 by George Johnson

July 27, 2008

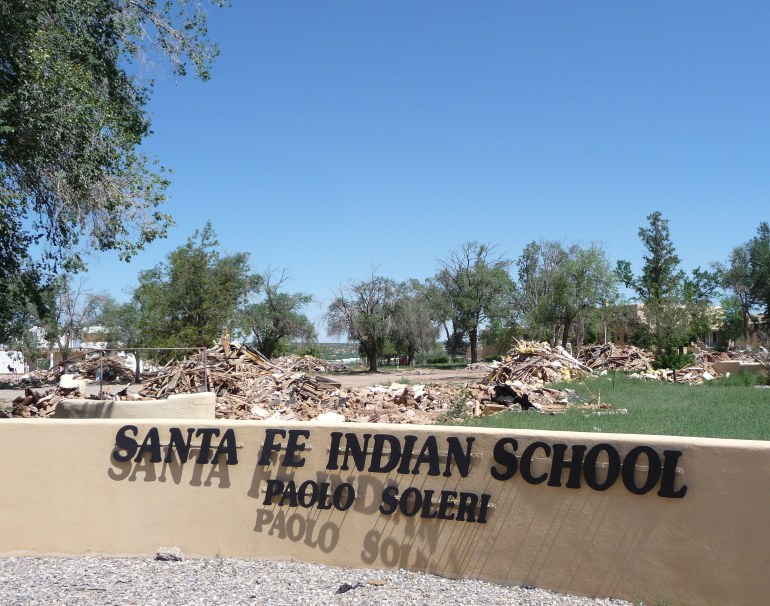

Demolition Derby

I was driving down Cerrillos Road yesterday, between stops at Home Depot and Trader Joe's, when I saw the destruction: half a dozen mounds of crushed brick and lumber piled on the grounds of the Santa Fe Indian School. A moment later I saw the wrecking crane demolishing the upper story of a large brick building. All of these were historic structures, but the All Indian Pueblo Council, exercising what it claims are its sovereign rights, decided to smash them to smithereens. This morning's New Mexican has the details (and quotes Councilor Miguel Chavez and his former colleague Karen Heldmeyer, who were watching from the sidelines).

With just a little notice, the story points out, valuable architectural items might have been salvaged and the properties properly documented for historians. But no. We won't even know what will be built on the suddenly vacant land until Monday, when the secretive organization issues a news release. For all we know it will be a casino.

All Joe Garcia, the Pueblo Council's chairman, would say is that the buildings had to be demolished because they might contain asbestos. How bizarre. As reporter Staci Matlock astutely noted, none of the workers were wearing masks. Tearing down buildings with asbestos shingles or insulation requires adherence to strict Federal and state environmental procedures. Not even the tribes can ignore them. If there are asbestos fibers in all that rubble then every worker, neighbor and passerby -- every student and employee of the school -- has been exposed to a dangerous carcinogen.

July 28, 2008

Postscript

Elaine Bergman of the Historic Santa Fe Foundation has posted pictures of the Indian School, before and after the destruction.

July 30, 2008

A day later than promised, the All Indian Pueblo Council issued a statement about the demolition, which is still under way, and it says next to nothing:

After completing various assessments over the past 5 years, the Santa Fe Indian School exercised its sovereign authority and due diligence to take action by demolishing buildings to remove the imminent health, safety, and security threats to protect the students and staff of SFIS, including the general public.

Meanwhile state and federal officials are reacting so obsequiously that you would think they were dealing with China instead of Indian tribes, which for all their blustering about sovereignty are part of the United States. According to Julie Ann Grimm in the New Mexican, the state environment department said it will "send a letter to school administrators offering our assistance monitoring any issues with asbestos or other concerns at the site." But if the buildings did contain asbestos, the fibers are already being released into the air -- and may well be drifting beyond the campus onto city and state lands.

The state referred the reporter to the feds, and the feds referred her back to the state. A spokesman for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regional office was no more forthcoming than the Pueblo Council:

Usually tribes conduct their own environmental programs. We usually work with tribes from a partnership perspective, not from an enforcement perspective.

But whenever regulatory authority is delegated to the tribes, it must be consistent with federal law. The proposed Desert Rock coal-fired plant on the Navajo Reservation cannot proceed without permits from the EPA. If the EPA has indeed given the tribes authority to regulate their own asbestos removal, they would still have to follow procedures at least as strict as federal standards. Imagine if it were otherwise.

Just before lunch I drove by the campus again. What I had seen on Saturday was barely the beginning. Numerous two-story brick buildings have been crushed. Raam Wong reports in the Journal that at least one of them dates back to 1890 and that 24 had been found eligible for placement on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Journal was late jumping on the Indian School story but reporter Raam Wong has moved in front of the pack with another piece today about the architectural treasures lost in the demolition. Many of the buildings that are being pulverized were renovated in Spanish Pueblo style under the direction of John Gaw Meem, and some, the Journal reports, may have contained WPA murals painted in the 1930s as part of the New Deal.

This year, in recognition of the 75th anniversary of the program, Kathryn Flynn, executive director of the National New Deal Preservation Association, asked to see the Indian School murals. Her request was denied, and she was told that the buildings contained asbestos and lead and were to be destroyed to build a museum and a commercial development.

Meanwhile the demolition seems to be on hold. When I drove by the site today, the heavy machinery stood among the ruins, parked and silent like the dinosaur statues out on the I-25 frontage road.

August 1, 2008

There is another scoop today in the Journal by Raam Wong: The manager for the construction company that is smashing up the buildings now says that there was indeed asbestos inside, but that it was "abated" before demolition began. He refused to elaborate but said that the school will issue a news release. Maybe it will explain why the public wasn't informed of these details a week ago.

Meanwhile the regulatory agencies have been nudged from their lethargy. Ron Curry, the state Environment Secretary, apparently decided to send a more strongly worded letter to the school than he had initially planned. And the EPA now reports that it was informed in advance about the project and will be reviewing the outcome on Monday. Maybe that is why work at the site appears to be in limbo.

The New Mexican has a lot to catch up on.

August 2, 2008

August 3, 2008

Indian Ruins

Saturday afternoon I parked on a side street off Cerrillos Road and walked toward the ruins of the old Santa Fe Indian School. Six large buildings -- five of them two storied -- stand in freezeframe, only partially demolished. A carefully carved wooden sign identifies one as the "Snake Building," as though it still mattered. Spared from the wreckers, a glass-paneled door hangs upright on its hinges with all its windows intact.

After launching a surprise attack -- on a weekend presumably to forestall intervention -- the Pueblo Council appears to have made a strategic retreat. Don't ask why. Beyond the iron picket fence is another country where only the impertinent ask questions.

The fence is marked with faded red-and-white signs: "Boundary Indian Reservation. No Trespassing." From what little history I can find, the United States Department of Interior contracted with the All Indian Pueblo Council in the 1970's to operate the school. Years later the campus became Indian trust land -- meaning that it is held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of the pueblos. But does that make it the legal equivalent of a reservation, a term generally applied to land occupied by a particular tribe?

More legal ambiguities are raised by wording on a billboard posted by Flintco, the native-owned construction company in charge of both the demolition and the building of a new health center: "Funded in part by the U. S. Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration." So there is another federal agency that may have some responsibility for oversight.

After I picked up the Sunday New Mexican from the driveway this morning, I turned immediately to the opinion section to see what the editors of our paper of record had to say. Nothing. But they did run an eloquent column by Alan Watson, who has spent much of his career working with New Mexico's tribes to restore historic adobe structures. It should have been on the cover page. As a member of the state's Cultural Properties Review Committee, Mr. Watson helped ensure that the pueblos were consulted about archeological artifacts beneath the site where the new convention center is being constructed. They apparently felt no need to reciprocate.

"It seems to me that consultation at its best is a two-way street," Mr. Watson wrote, "and that in this case representatives of the school, by avoiding consultation with the division, have responded to good will with bad intentions."

Whether the recent demolition was legal or illegal (as I strongly suspect) may be an issue we will never see resolved. What I am certain of is that the school's officials have set a poor example of civic leadership to their students, especially by their destruction of irreplaceable murals by such revered alumni as Pablita Velarde. They have acted as disgraceful neighbors to the community at large.

The Journal makes a similar point in a circumspectly worded lamentation.

No signs of murals are visible within the wreckage from Cerrillos Road. Maybe they were painted over years ago. More secrets guarded on this 100-acre island, a Duchy of Grand Fenwick in the middle of Santa Fe.

August 7, 2008

Since time is a one-way arrow, it is not possible to go back to 1890 and right some of the wrongs that came with the establishment of the Santa Fe Indian School. In One House, One Voice, One Heart, a moving oral history of the school, Sally Hyer describes the bleakness of the early years -- the bland institutional food, the homesickness, the military drills, the strict segregation of the sexes, and a policy of forced assimilation. But she also writes of dedicated teachers, touch football amidst the chamisa, and an accomplished school band.

Some commentators, seeking to justify why leaders of the All Indian Pueblo Council would so callously destroy the historic buildings entrusted to them by their fellow citizens, have speculated that it was because of bitter memories of a stereotypical Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school. Judging from the fond recollections of some of the students, the theory doesn't ring true.

"The school was a big change. Like sleeping on a good bed. And eating on a table," recalled a student who arrived in 1919. "We ate at home on the floor." A Jemez girl remembered the pride she felt when she was given her first pair of new shoes. Some even missed the marching: "Oh, it used to be so beautiful to watch them. To see them move all at the same time!"

From there conditions only improved. Around 1930, with a new progressive leadership at the Department of the Interior, the school underwent a renaissance. The military exercises were replaced with traditional dances. An art education program was established. The curriculum was expanded to include not just the history of the conquerors but the history of the tribes. Even the food got better. Students from all over New Mexico were lining up to get in.

This transition to a more respectful education was marked by the renovation of campus buildings, the ones that are currently being demolished, from institutional red brick to Spanish Pueblo revival style. Under the direction of Dorothy Dunn and then Geronima Montoya of San Juan Pueblo, students worked with artists to paint murals on the walls. An institution that had originally been imposed on New Mexico's natives by a paternalistic government had been adapted to and then absorbed by them as part of their culture.

The saddest moment in the book comes in 1962 when the federal government unilaterally closed the school and transferred most of its functions to Albuquerque. "I cried because it wasn't like it was here in Santa Fe," said a student from San Juan. "I think we all felt about the same way."

But the story didn't end. In 1977 under the Indian Self-Determination Act, the Pueblo Council reached an agreement with the BIA to operate the Albuquerque school. Four years later, just after the 300th anniversary of the Pueblo Revolt, the school came home to Santa Fe to remain under Indian control.

What followed, as recounted in the book (published in 1990) has been a triumph. Academic performance improved, and the school earned national and state accreditation. In recent years it embarked on the construction of what from all appearances will be an attractive new campus. Why then the secretiveness, the suddenness, the irreversibility of the decision to crush all those old buildings -- those memories -- without any notice to the community that helped make the school a success? It is hard to interpret the act as anything but an overt, xenophobic expression of contempt.

While the school and the Pueblo Council continue their policy of public nondisclosure, the Journal persists in its investigation. (The New Mexican appears to have given up.) There is indeed documentation, we now learn, that the asbestos was removed from the buildings before they were destroyed. But the less tangible poisons released into the air will linger for a long time.

August 9, 2008

Judging from a brief statement by Katherine Slick, the State Historic Preservation Officer for New Mexico, there is reason to believe that the demolition of the old Santa Fe Indian School was a violation of federal law. The National Historic Preservation Act, passed by Congress in 1966, established representatives like Ms. Slick (called SHPOs and pronounced to rhyme with "hippos") to serve as liaisons with Washington. At a meeting on Friday of the State Cultural Properties Review Committee, Ms. Slick referred to Section 106 of the act, which requires federal agencies (in this case the Bureau of Indian Affairs) to consult with the appropriate SHPO on any project that (1) involves the expenditure of federal funds and (2) affects property on or eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

Both conditions apply. The Journal has reported that the BIA itself determined in 1994 that the buildings were eligible for the register, and the new campus is being constructed with federal money. Yet the agency is claiming to have no authority -- or responsibility -- in the matter.

It's reasoning is unclear. The fact that the property became Indian trust land in 2000 doesn't seem germane: Sixteen pages of federal regulations (36 CFR Part 800 -- Protection of Historic Properties) describe how Section 106 is to be implemented, and §800.5 forbids "transfer, lease, or sale of property out of Federal ownership or control without adequate and legally enforceable restrictions or conditions to ensure long-term preservation of the property's historic significance."

There are exceptional circumstances under which historic properties can be destroyed, but only according to a strict process of consultation spelled out in the regulations. The regulations also require public notification and even provide for public input.

Is there any way then that the demolition could have been legal? I can think of only one scenario -- and it's a doozy. In dealing with structures on Indian land, a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer can take the place of the SHPO. And under §800.2

An Indian tribe or a Native Hawaiian organization may enter into an agreement with an agency official that specifies how they will carry out responsibilities under this part, including concerns over the confidentiality of information.

But §800.11 goes on to restrict confidentiality to cases where the Secretary of the Interior agrees that disclosing "the location, character, or ownership of a historic property . . . may cause a significant invasion of privacy; risk harm to the historic property; or impede the use of a traditional religious site by practitioners."

Surely that wouldn't apply in this case.

Ms. Slick noted that three of the historic campus buildings have not yet been destroyed. There is still time for intervention by a federal court.

August 11, 2008

There may be a perfectly reasonable explanation for the contradictions revealed this morning by Tom Sharpe's excellent reporting in the New Mexican on events at the Santa Fe Indian School. But consider:

1. According to a notice filed with the Environmental Protection Agency by the demolition contractor, Flintco, 104,746 square feet of asbestos-containing material -- almost 2 1/2 acres' worth -- was removed from 15 buildings before they were demolished. Scott Taylor, the project manager, acknowledges that the process requires "negative-pressure tents that looked like giant balloons" to contain the debris on site. Quite a spectacle one would think, yet merchants directly across from the school on Cerrillos Road noticed nothing.

2. The EPA filing also stated that the debris was to be transported, by a company called Complete Decon Inc. of Phoenix, to a landfill near Mountainair, New Mexico. But on August 4 -- more than two weeks after the demolition began -- the filing was changed. Actually the asbestos had been dumped at Painted Desert landfill in Joseph City, Arizona. Mr. Taylor of Flintco says that's because they got a better deal. The change of venues would also make Flintco's story harder to verify. But there are ways. Landfills licensed to receive asbestos are required by federal law to keep records -- and these are public documents. We hope that Mr. Sharpe and Raam Wong of the Journal will follow up.

The next most striking revelation in today's stories -- there are two, plus sidebars on the history of Indian education and a roster of the destroyed buildings -- is the seeming incompetence of the EPA's Dallas office, which is responsible for New Mexico. Despite the public outcry over the demolition, the EPA has sent no one to Santa Fe to confirm that proper procedures were really followed. "Sometimes, we do, but in this case, we didn't," said Elvia Evering of the EPA's asbestos program.

Mr. Sharpe also addresses the sovereignty issue.

"The status of the land as federal trust land is what makes the land exempt from state or local land-use regulations," said Rebecca Tsosie, a Yaqui and professor of law at Arizona State University.

But that is not the point. The issue is whether there have been violations of federal laws -- the Environmental Protection Act and the Historic Preservation Act. The silence of school and pueblo council officials only adds to public suspicions. Not one of them would talk to Mr. Sharpe or return his calls.

August 13, 2008

When New Mexico's pueblos describe themselves as "sovereign nations" that does not mean sovereign like Canada or Mexico, but sovereign like Oklahoma, Arizona, or any of the other 50 states. All are parts of a greater whole ruled by federal law. If the sovereign state of New Mexico decided to demolish the Palace of the Governors or the New Mexico School for the Deaf -- state-owned property on the National Register of Historic Places -- it would have to abide by the federal Historic Preservation Act.

For that matter, Section 106 of the act ensures that even the sovereign nation of the United States would have to follow the regulations if, say, it wanted to tear down the old Federal Courthouse downtown.

Yet the misunderstanding persists that tribal sovereignty was enough justification for leveling the buildings on the old Santa Fe Indian School campus. Zane Fischer falls into this trap in his column today in The Reporter.

As noted here before, the school buildings had been designated eligible for the register, and the preservation act gives eligible buildings the same protection as those already on the list. And for good reason. An unscrupulous owner of an eligible property might rush to bulldoze it before Congress got around to making the designation official.

The only ambiguity with the Indian School is whether it is the Pueblo Council or the Bureau of Indian Affairs that has violated the law. Either the BIA disregarded the requirement to put protections in place back in when the campus became Indian trust property (the key word here is "trust") or the protections were there and the Pueblo Council just ignored them. There must be papers and deeds -- public records -- recording the transaction. Therein lies the placement of the guilt.

August 14, 2008

A reader who works for the state government (and has requested anonymity) sent me a copy of a draft document, dated July 14, 1989, nominating the "Santa Fe Indian School Historic District" for the national register. Prepared by Sally Hyer, it describes in heartbreaking detail what has been lost. (Ms. Hyer is the author of One House, One Voice, One Heart, described in my dispatch of August 7.)

In its own evaulation, the BIA determined that the buildings were eligible for the register in 1994. Why the agency failed to follow through with a nomination, as required by Section 110 of the preservation act, has yet to be determined.

The document is posted here in two parts.

"Santa Fe Indian School Historic District," Draft National Register of

Historic Places district nomination, prepared by Sally Hyer.

1. A description of the buildings

August 15, 2008

On September 12, 2002, the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division sent a letter (posted here as a pdf download) to the Bureau of Indian Affairs office in Albuquerque expressing concern about the disposition of the historic buildings on the Santa Fe Indian School campus. The school was about to embark on the construction of its new campus, on the north side of the property, and as required by law, it had submitted an environmental assessment.

But the evaluation, conducted by a local contractor called Marron and Associates, apparently failed in its responsibility (under the National Environmental Protection Act) to address the impact of the project on more than 20 buildings "with substantial historic integrity" and judged to be eligible for the national register.

The letter went on to remind the BIA of its duties under Section 106 of the Preservation Act. Though Marron and Associates stated that "no buildings will be razed" -- an interesting point in itself -- Jan Biella, the acting State Historic Preservation Officer, noted that their abandonment would constitute "demolition by neglect," as defined by Federal code.

Incorporating historic buildings into new construction projects is required, whenever possible, by Federal law.

Whether the letter was ever answered remains unknown. What seems clear is that as of 2002, apparently before the campus's conversion to trust land was complete, the BIA was fully aware of its obligations under the Preservation Act. And, it now appears, it may have disregarded the Environmental Protection Act as well.

updates

I've confirmed from another source that the letter sent by the Historic Preservation Division to the Albuquerque office of the BIA was never answered. Nor was an earlier letter sent in 2001 to the Director of the BIA in Washington, also complaining about deficiencies in the environmental assessment. The only response was some new language added to a revision of the Marron report dated May 20, 2002:

But that never happened.

August 16, 2008

I've found the law under which the Indian School campus was put into trust: Sections 821 to 824

Therefore we request a more detailed scope of work with a clear

indication of your future plans for all the historic buildings

within campus, and preferably, demonstrat[ing] an effort on the part

of the designers to creatively and fully utilize the cultural

resources.

Many of the existing buildings will be vacated after the

construction of the new buildings. All existing facilities will

be used to house staff and programs for health, cultural, or

educational purposes. All vacated buildings will be maintained to

the extent they have been maintained in the past. A study will

be made as to the best use of the existing buildings. This study

will be coordinated with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the new

Mexico Historic Preservation office.

The act makes clear that the land remains subject to "encumbrances, rights of way, restrictions, or easements of record." Those would presumably include the Section 106 restrictions involving historic preservation that the BIA should have imposed. If these exist, they should now be attached to the deed: United Sates General Land Office Plat of the United States Indian School Tract, March 19, 1937, Book 363, Page 024 -- on file at the Santa Fe County Clerk's office downtown.

Most important, perhaps, the act also describes how the trust can be revoked if it is misused.

August 19, 2008

This page is getting long and heavy. Soon I will start another. First, however, a recap of where the Indian School issue stands:

Culpability of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

Culpability of the All Indian Pueblo Council

All these matters are subject to investigation by the Inspectors General of the Department of the Interior and the EPA and by the Justice Department. The campus is not owned by the pueblos. It is public land that was loaned to them -- under certain conditions -- through an act of Congress. If the allegations stand, the trust can be revoked.

Here again are the relevant documents:

For a continuation of the story, please see Part 2

The Santa Fe Review