In the 1920s, on the same block where the Gilberts now live, the Cinco Pintores — Will Shuster, Fremont Ellis, Willard Nash, Walter Mruk, and Josef Bakos — built their adobe studios. Ned Hall, an anthropologist and great Santa Fean who died last year, used to tell friends about the years he spent, all but abandoned after his parents’ divorce, shivering in a lean-to behind the Bakos place and walking down to Marcy Street for school. In Ned’s recollection, the artist and his mistress, all friends of the Hall family, were drunk half the time and only interested in the boarding income. The details, described in Ned’s memorable book, An Anthropology of Everyday Life, give a less romantic view of the Pintores than found in the tourist brochures.

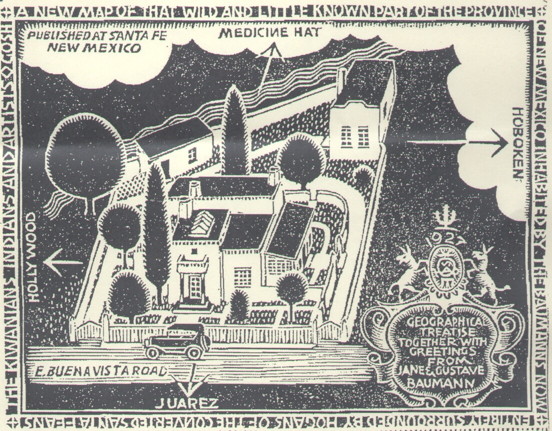

Baumann Greeting Card. From the Historic Home Tour brochure.

The writer Mary Austin lived a block downhill on Monte Sol in what was to become another of entrepreneur Gerald Peters’s acquisitions and is now just one more high-end gallery. Bearing west from there along the Acequia Madre, running with snowmelt, I reached Old Santa Fe Trail, following it south a few blocks to Camino de Las Animas (Road of the Spirits), where the woodcut artist, Gustave Baumann, once lived.

The house, with Baumann’s subtle decorations still intact, was open for the first time as part of the Historic Santa Fe Foundation’s annual tour, and the street was jammed with cars. Inside, the rooms were packed shoulder-to-shoulder and chest-to-chest with visitors. I wonder how many of them left disappointed. There was no Subzero refrigerator, no slate counter tops, no Viking range — just a small, functional kitchen. The ceilings didn’t soar. The bathroom was just a bathroom. In those days, the mad poet Witter Bynner lived a block away on Buena Vista Street in more opulent surroundings, and the writer Oliver LaFarge was around the corner on Old Santa Fe Trail.

The rich people then were often the black sheep of Eastern dynasties thriving on inheritances and trust funds and supplying the artists with booze. Las Animas dead-ends at a bridge and footpath that once led to El Delirio, the estate (now the School for Advanced Research) where the White sisters, Santa Fe’s Paris and Nicky Hilton, presided over their legendary bacchanals.

I followed the path to Garcia Street and two other stops on the tour, more artist hideaways I’d never seen: the Irene von Horvath house, entered through the back of the parking lot for Geronimo restaurant, and the practically vertical Sheldon Parsons residence near the foot of Cerro Gordo Road. These places were also packed like subway cars with people like me who paid five dollars for a ticket, a fantasy, a donation to a good cause. Next year, I bet, the Historic Santa Fe Foundation could charge $10 without the slightest drop-off in sales. Maybe the quirkiness of Santa Fe has been flattened forever by money and bad taste, but there is no shortage of dreamers longing for a glimpse of more interesting times.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review