Midway through May,

a page appeared on Facebook imploring the secretive administrators of the Santa Fe Indian School not to tear down the Paolo Soleri amphitheater. Day after day, heartfelt testimonials poured in from students and alumni sharing memories of graduation ceremonies at the Paolo (

the most recent was on Friday) and the mind-blowing concerts they attended there.

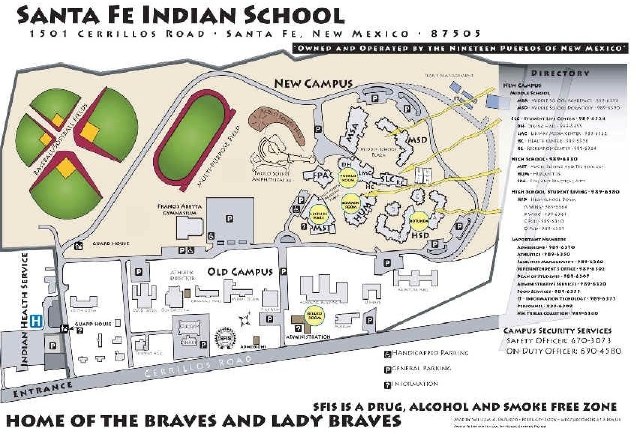

Santa Fe Indian School, May 30, 2010

The possible demolition is a rumor, but there are good reasons to fear that it is true. As readers of my past installments know, school officials have already flattened — with no warning or consideration for anyone’s feelings but their own — the beautiful old buildings of the historic campus, and they have cut down a forest of old shade trees. What happened was illegal. The only question is whether it is the Bureau of Indian Affairs or the All Indian Pueblo Council that is to blame. Possibly they acted in collusion. Whoever is responsible has gotten off scot-free. (For a condensed version of the legal issues, please see my letter of September 25, 2008 to the Interior Department.)

With the new public Facebook page, some of the school’s former students — who were as shocked as anyone when the bulldozers rolled in — finally have a forum for expressing their sorrow. Here is how Audrey Archuleta of Española put it:

After what they did to the trees on that campus,

this is not surprising. Whoever is making these

decisions should be ashamed of themselves. What

else can you say? Every time I pass by that campus

now it makes me angry, ashamed, and sad all in the

60 seconds it takes to drive by.

This is from Lisa Elkins of Thoreau, New Mexico, at the edge of the Navajo Nation:

My mom grew up on that campus. It was a shock to

come home and find that they destroyed that school,

NO TREES, NO HISTORIC buildings. It was a crying

shame! Now this??

Norma C. Romero, a member of Taos Pueblo, wrote about the sadness she felt over how the campus has been laid bare and turned into a dust bowl:

Paolo Soleri is our last stand. Our Grandparents and

many generations have put the foot markings on the

ground on which it stands. What has become of the pride

we all each held? This is a sad day not only for me,

but thousands who share the same feelings.

So where is one to turn? The Old Santa Fe Association and the Historic Santa Fe Foundation have been too timid to demand an investigation. Withering under political pressure, the New Mexico State Historic Preservation Office (called the SHPO) failed to intervene. Within the SHPO’s office I know employees who are sickened by what was allowed to happen on their watch. But they are afraid to speak out lest they lose their jobs. I don’t know what I would do in their situation.

In theory, both the BIA and the SHPO are within the jurisdiction of the Interior Department, whose Inspector General, Earl Devaney, is required to investigate allegations of crimes. He apparently can’t be bothered. Yesterday in reply to my latest inquiry, I heard from one of Mr. Devaney’s assistants, Scott Culver. His title is Deputy Assistant Inspector General. One of his functions is apparently brushing off people who inconvenience his boss by asking that he do his job.

Here is Mr. Culver’s nonresponse to my letter:

We understand this issue has been raised with the Bureau of Indian

Affairs and the State of New Mexico Office of Cultural Affairs --

Historic Preservation Division, which are the appropriate forums for

your complaint. Thank you for contacting our office.

What a classic run-around. I originally wrote to the Inspector General in September 2008 after being stonewalled by the BIA and after the New Mexico SHPO dropped the matter like a hot potato. So I appeal to the next level of the hierarchy, the Inspector General, and after repeated inquiries am referred by Mr. Culver back to the very culprits I am complaining about. He obviously read none of the supporting documents I submitted.

Through his own inaction, Senator Udall has been as complicit in the cover-up as Mr. Devaney. (Here is my latest letter to the Senator’s office.) Given this stalemate, the only recourse would seem to be the Justice Department. Hence this other letter I recently sent to Kenneth Gonzales, the new United States Attorney for New Mexico. Though not a tribal member, Mr. Gonzales graduated from high school in Pojoaque and worked for Senator Bingaman on Indian affairs. Will he be sympathetic to the politically powerful Indian Council or to the pueblo people whose memories have been destroyed?

Just like the buildings that were razed in 2008, the Paolo Soleri, named after the Italian-born architect and built by students from the Institute of American Indian Arts, was listed in 1989 as a “historically contributing” building because of its Neo-Expressionist architecture. (The details are in a 1989 document titled “Santa Fe Indian School Historic District,” by Sally Hyer. I have posted it in two parts: A description of the buildings and Historical context.)

It is still possible that the Paolo Soleri can be saved. It is also still possible that the bureaucrats who destroyed the rest of the old campus can be brought to justice. But nothing is likely to happen unless the impassioned souls who have flocked to the Save Paolo Soleri Facebook page demand to be heard.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Postscript

Digging through my files this morning on the Santa Fe Indian School, I see that one of my earlier communications with the Department of Interior, dated March 11, 2009, was also with Scott Culver. He assured me that his office was reviewing the matter and “will inform you of the disposition of your complaint.” Of course that never happened. I waited three months and then contacted Senator Udall on June 8, 2009. Four months after that I got a call from one of his staffers, Raven Murray, assuring me that they were pressing the matter and that Interior had assured the Senator’s office that a legal opinion was forthcoming. All that, it seems, was smoke and mirrors.

I was about to jump over to KUNM, hoping that the hour-long Indian chants had not yet begun, when there was an advertisement for the

I was about to jump over to KUNM, hoping that the hour-long Indian chants had not yet begun, when there was an advertisement for the