On Sunday morning as Tom Udall welcomed the people who had come to commemorate his father’s extraordinary life, the Senator explained why the event was taking place at the Paolo Soleri amphitheater at the Santa Fe Indian School. It was Stewart Udall who, as Secretary of Interior, contacted Mr. Soleri more than 40 years ago and asked him to work with students from the Institute of American Indian Arts to design and build the theater with its unique Flintstone-like style. Later when the elder Mr. Udall needed to raise money to defend the claims of Navajo uranium miners, he persuaded Pete Seeger and Edward Abbey to perform there. When his wife, Lee, died nine years ago, it seemed only fitting that the services take place, on Mother’s Day, at the Paolo Soleri. Now on Father’s Day it was Stewart’s turn.

Senator Tom Udall at the Paolo Soleri, June 20, 2010

“The Paolo Soleri is a very special place for us,” the Senator said. “It is specifically where dad asked that we do the celebration.”

Joshua Madalena, governor of Jemez Pueblo, gave a blessing, and one by one, friends, dignitaries, and family members took the stage. There were folk songs — “He was a Friend of Mine,” “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” and “This Land Is Your Land” — and readings from the grandchildren.

And throughout this all, there was not a mention of the fact that the unique amphitheater we were all sitting in is about to be destroyed.

At one point the Senator asked governors from the various tribes — who as members of the All Indian Pueblo Council have approved the demolition — to stand and take a bow. “Thank you,” Mr. Udall said, “for running a good school and focusing on education.” Tacit approval perhaps of Superintendent Everett Chavez’s repeated declarations that the theater must be removed because it has become inconsistent with the school’s “progressive” educational mission.

It was a morning of surreal ironies. We were reminded during the speeches that it was Stewart Udall who was so crucial to the passage of not just the Wilderness Act and the Endangered Species Act but also the National Historic Preservation Act, which, properly applied, might have saved all those buildings on the old campus as well as the Paolo Soleri. It’s too late now.

Calabaza Consultants, the Native-owned PR firm recently hired by the school to more efficiently deliver its obfuscations, has announced that two previously scheduled concerts (Lyle Lovett and Modest Mouse) will be allowed to continue before the Paolo Soleri is closed. In return the promoter, Jamie Lenfesty of Fan Man Productions, who stood to lose money if the shows were cancelled, grudgingly agreed to give up the fight. Not much more than a week ago, Mr. Lenfesty called on members of the New Mexico Cultural Properties Review Committee to help save the theater. “There will never be another Paolo Soleri,” he told them. “There is a spirit and a soul. Every musician I have had the pleasure of presenting there has left Paolo moved by its power.”

Now, in the press release announcing his dispensation, he recognized the “unfortunate reality” that the Paolo Soleri is on school property and agreed with the Pueblo Council that it “would be better suited to a different location where the activities of concert goers would not be deemed a threat to education and student life.”

In the end, it all came down to the bottom line.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

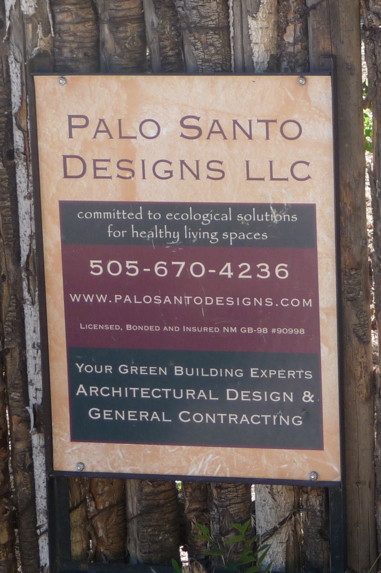

Almost every morning for the last two weeks, I’ve driven up the hill to St. John’s College to sit in on an event, sponsored by the Santa Fe Institute, called Sustainability Summer School. And every morning as I depart, the jackhammering and scraping of rock against steel has continued as the couple from Houston builds a “green” home.

Almost every morning for the last two weeks, I’ve driven up the hill to St. John’s College to sit in on an event, sponsored by the Santa Fe Institute, called Sustainability Summer School. And every morning as I depart, the jackhammering and scraping of rock against steel has continued as the couple from Houston builds a “green” home.