We’ve written here before about the great boondoggle of 1930, in which the City of Santa Fe was persuaded to give the most valuable piece of its Northwest Quadrant to a real estate speculator (and later governor of New Mexico) in return for a small cut of the proceeds. (Please see

The Dempsey Papers, April 9, 2007.) The parcel, 2,000 acres of public commons granted to the town by King Philip V of Spain, is now the site of Don Tishman and Eddie Gilbert’s Zocalo condominiums, the Las Estrellas subdivision, Garrett Thornburg’s corporate headquarters, and numerous Northside mansions off Bishop’s Lodge Road, including Governor Richardson’s. The city hung on to the rest: 2,770 acres of hilly, arroyo-cut scrub land whose highest and best use was gathering firewood and piñon nuts, accommodating hobo camps, and disposing of old cars, mattresses, and recently swigged beer cans. The southwest corner of the grant became the city dump and a Japanese internment camp and is now home to the Buckman Road Transfer Station. But most of the area, classified as “Mountainous and Difficult Terrain,” has sat vacant. Because of the steep slopes, it would be an expensive place on which to build.

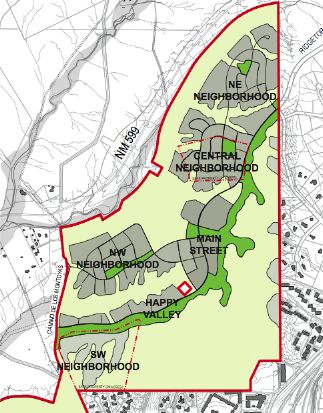

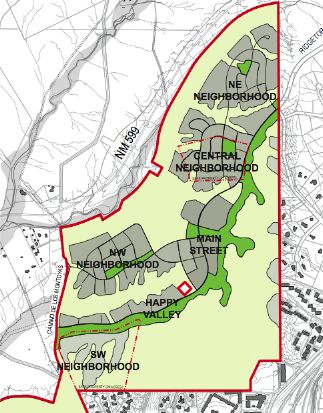

Northwest Quadrant Master Plan

Undaunted, the City Council took the first steps last week toward rezoning 540 acres of the old grant to accommodate the eventual construction of six new neighborhoods. There, it is envisioned, teachers, nurses, police officers, fire fighters, and other aspiring members of the middle class will be able to buy reasonably priced homes just two miles from the Plaza. The enormous development costs would be offset, in part, from the expanded tax base and $10 million in hypothetical government grants.

Described in the impressively illustrated Northwest Quadrant Master Plan, the project is an urban designer’s dream. There would be a Jane Jacobs-like neighborhood called Main Street — a dense, vibrant blend of townhouses, apartments, “live-work” units, and small businesses centered around a community plaza. There would be Happy Valley (really!), a “mixed use, arts-and-crafts community” of rowhouses and cottages that “will thrive around its diversity.” There would be more staid neighborhoods like those you might see at Rancho Viejo, and to help subsidize the whole effort, a ritzier Southwest Neighborhood of larger houses on bigger lots. All these places would be neurologically connected by a “backbone” parkway lined with hiking and biking trails. People rich and poor, of all races, creeds, colors, and sexual orientations, would bicycle to dinner or to a concert in the park — and when they had to leave their comfortable enclave they would get in their cars, funnel out through the single entrance on Ridgetop Road, and merge onto the highway for the short trip to town. In case of an emergency evacuation, a back gate could be opened onto Camino de Los Montoyas.

That is the kind of monster that is born when idealistic visions collide with political reality. It would be good if Santa Fe had more affordable housing on the picturesque Northside. But to keep from undermining existing neighborhoods like Casa Solana with an intolerable amount of cut-through traffic, the proposed new community would be sealed off from the rest of town. It wouldn’t really be part of Santa Fe.

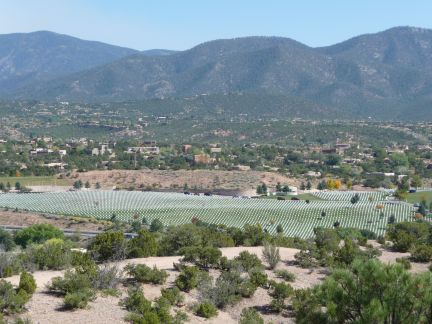

View from Main Street

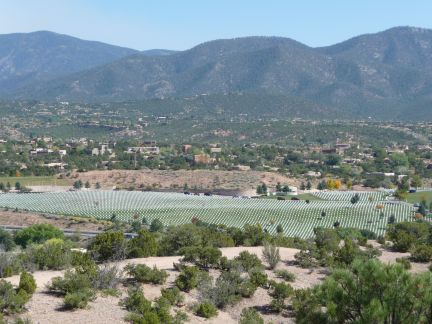

On Saturday, to improve my mental map of the area, I parked along Los Montoyas and walked uphill on a steep, eroded dirt road that skirts the southern edge of Happy Valley. There were mounds of trash, old sofas, and broken bottles. All four walls of a PNM electrical substation were smeared with graffiti. (This is where, two summers ago, a young vandal electrocuted himself while trying to tag a 115,000-volt transformer.) But if you blur over the details, this is a magnificent piece of land. Near the site of the neighborhood to be called Main Street, I looked out from the top of the highest hill. Thompson Peak and Atalaya Mountain formed a striking backdrop to the National Cemetery, where rows of white markers undulated through green hills. Even Zocalo looked good from up there.

I thought about other ways that the city might use this land, as King Philip decreed, for the commonweal. Maybe when the economy improves, some of the choicest homesites — comparable to the best in La Tierra or Las Campanas but right in town — could be sold to a high-end developer, whose clients could afford the gravity-defying construction costs. The proceeds from the sales could be used to expand programs for down-payment assistance and low-interest rehab loans — subsidies to improve neighborhoods that exist on the ground instead of in architectural cyberspace. The $10 million in grants that the Northwest Quadrant would consume could go instead to projects like the one on West Alameda, where dilapidated public housing is to be bulldozed and replaced with a mixed-use development. The lower slopes of the quadrant might be a relatively economical place to build workforce housing. But most of these rollercoaster badlands beg to be cleaned up and turned into open space, Santa Fe’s Central Park in the wild.

There is only so much you can do to fight geography. The primary reason that affordable housing is mostly on the Southside is not a matter of social injustice but of practicality. The land is flatter there.

Overlooking Happy Valley

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review