Griffith Observatory, Los Angeles. photos by George Johnson

Landscrape Architecture

It seemed like a really good idea a few years ago when the Canyon Neighborhood Association began pushing for the conversion of the old hydroelectric site at Camino Cabra and Canyon Road into a public park. The area, closed off for decades, was covered with native grasses and wildflowers shaded by towering evergreens and stately deciduous trees — an inviting mountain meadow cordoned off by an ugly chainlink fence. The plan was to create a “passive park” — no bright lights, no basketball courts or soccer fields, just a quiet patch of land where a person could sit beneath a tree and enjoy nature. All that was required, as far as I could see, was to open the gate and let people in. Nothing of course is ever that simple.

Early last fall the backhoes, concrete mixers, dirt rollers, and dump trucks began parading in and out. Five and often six days a week, living nearby has been like living in an industrial zone: the scraping and banging, the beeping of the backup alarms, the gulping of diesel and gasoline, and the spewing of exhaust fumes.

An old, seldom used dirt driveway leading beyond the park to a water pumping station had to be improved. So day after day a worker with a roadgrader spent most of an eight-hour shift driving back and forth, back and forth, compacting the soil. Meanwhile men with jackhammers tore up the corners of the intersection to make the sidewalks ADA compliant. All along an old arroyo that borders the site, deep cuts were excavated to install retaining walls.

The saving grace was knowing that the project was scheduled to be finished at the end of 2009. Suffering is endurable when you know it is finite and for the common good. When the deadline slipped to January 20, I looked forward to the completion as my birthday present. But that day came and went, and now almost four months later construction is still going on.

A passive park, it might seem, would be one that people walked or bicycled to. The city mandated instead that there be a concrete parking lot. So a big chunk of the area was planed flat and compacted — another noisy, polluting, energy-guzzling process that lasted for weeks. There had to be picnic tables, and the picnic tables had to be on concrete islands connected by wide concrete walkways. An extensive sprinkler system had to be installed.

Part of the enterprise involved restoring the dilapidated building that once housed the hydroelectric plant and turning it into a community center and museum. A great idea but one that requires putting in restrooms along with the plumbing to accommodate them. The building, which once generated power, would now consume it. So more work had to be done to tie it into the city’s electrical grid.

As a result of all the frenzy, much of the natural vegetation is gone. Truck loads of new top soil must be hauled in and truck loads of excavated dirt hauled out. The final step on the agenda is using spraying machinery to “hydroseed” what had already been grassy land. After that will come years of weed control as Russian thistle, kochia, and other Eurasian invaders thrive in the niches inevitably created in disturbed soil. The meadow had to be destroyed in order to save it.

I remain optimistic about the final outcome and grateful for the time some of my neighbors have devoted to the project. The restoration of the old building has been authentic and expertly executed. I like the new coyote fence that now surrounds the grounds and the serpentine walkway along what had been for pedestrians a treacherous stretch of Canyon Road. But I’m still left wondering why the creation of a peaceful little park had to become such a big deal.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

A Visit to the New Power Plant Park

The Power Plant Park on Canyon Road

Friday morning I met my friend Mac Watson at the new park on Canyon Road where, in his role as a historic conservationist, he is rehabilitating the old hydroelectric building. He introduced me to Victor Johnson, the landscape architect for the project, and we embarked on a tour of the grounds. The concrete parking slab doesn’t appear nearly so vast when you’re standing right on top of it, and Mr. Johnson was quick to note that there had been no meadow on this corner of the site, just a dark, oppressive thicket of Siberian elms, Santa Fe’s most reviled weed tree. He also noted that the grass in the rest of the park, wiped out by the construction, will be replaced not by hydroseeding, as originally planned, but by hand.

I hadn’t meant to direct my criticism at the design of the park — given the constraints he was handed, Mr. Johnson has done a graceful, aesthetically pleasing job — but with how the demands of bureaucracy turned what could have been a simpler, low-key endeavor into such an intensive development.

The reason for the high concrete-to-grass ratio is that the city decided each picnic table, no matter how distant from the parking area, had to be handicap accessible. (Concrete rather than packed gravel was used, Mr. Johnson said, to reduce the cost and difficulty of long-term maintenance.) Should four separate parties of picnickers in wheelchairs or scooters arrive simultaneously they can all be accommodated, and with pathways so wide as to allow for two-way traffic. The Americans With Disabilities Act is an important piece of legislation, but here it has been carried to an extreme — at the expense of the natural habitat.

The day before the tour, Chip Lilienthal of the City Facilities Division assured me in an email that “Phase 1” of construction will finally end this month. Alas, there is to be a Phase 2: building the restrooms and completing interior work on the old power station, which will serve as the focus of a Water History Museum. That part is definitely going to be worth the wait. As Mac Watson reminded me, the harnessing of the Santa Fe River for electrical power a century ago was the first step in a sequence that led to a communal resource becoming commoditized. From then on water was a product to be impounded, sold, piped to profitable new locations. Development began dictating supply, instead of vice versa, and the town kept growing larger and drier. The new Power Plant park will be a place to step off the treadmill for a moment and consider the consequences.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

A Walk Back in Time

On a recent Sunday, with May’s gale force winds temporarily subsiding, I took a long, circuitous walk downtown, trying to imagine what Santa Fe was like when young artists outnumbered retirees and wealthy financiers. Detouring over to Camino del Monte Sol, I passed by Eddie Gilbert’s estate where an American flag was flying out front. The New Mexican had just reported that Mr. Gilbert, whom we’ve met here before, is selling his once formidable real estate empire, BGK Properties, at what is apparently a fire sale price. I half expected to see a moving van.

In the 1920s, on the same block where the Gilberts now live, the Cinco Pintores — Will Shuster, Fremont Ellis, Willard Nash, Walter Mruk, and Josef Bakos — built their adobe studios. Ned Hall, an anthropologist and great Santa Fean who died last year, used to tell friends about the years he spent, all but abandoned after his parents’ divorce, shivering in a lean-to behind the Bakos place and walking down to Marcy Street for school. In Ned’s recollection, the artist and his mistress, all friends of the Hall family, were drunk half the time and only interested in the boarding income. The details, described in Ned’s memorable book, An Anthropology of Everyday Life, give a less romantic view of the Pintores than found in the tourist brochures.

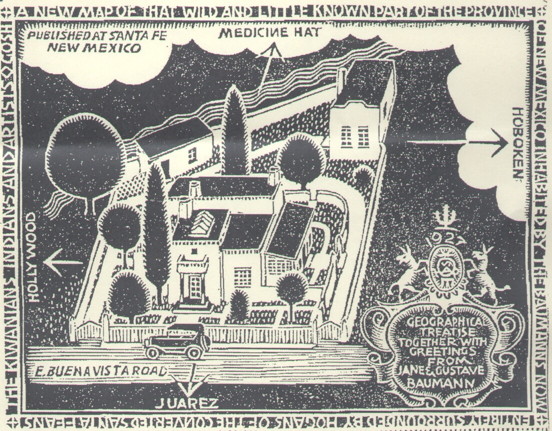

Baumann Greeting Card. From the Historic Home Tour brochure.

The writer Mary Austin lived a block downhill on Monte Sol in what was to become another of entrepreneur Gerald Peters’s acquisitions and is now just one more high-end gallery. Bearing west from there along the Acequia Madre, running with snowmelt, I reached Old Santa Fe Trail, following it south a few blocks to Camino de Las Animas (Road of the Spirits), where the woodcut artist, Gustave Baumann, once lived.

The house, with Baumann’s subtle decorations still intact, was open for the first time as part of the Historic Santa Fe Foundation’s annual tour, and the street was jammed with cars. Inside, the rooms were packed shoulder-to-shoulder and chest-to-chest with visitors. I wonder how many of them left disappointed. There was no Subzero refrigerator, no slate counter tops, no Viking range — just a small, functional kitchen. The ceilings didn’t soar. The bathroom was just a bathroom. In those days, the mad poet Witter Bynner lived a block away on Buena Vista Street in more opulent surroundings, and the writer Oliver LaFarge was around the corner on Old Santa Fe Trail.

The rich people then were often the black sheep of Eastern dynasties thriving on inheritances and trust funds and supplying the artists with booze. Las Animas dead-ends at a bridge and footpath that once led to El Delirio, the estate (now the School for Advanced Research) where the White sisters, Santa Fe’s Paris and Nicky Hilton, presided over their legendary bacchanals.

I followed the path to Garcia Street and two other stops on the tour, more artist hideaways I’d never seen: the Irene von Horvath house, entered through the back of the parking lot for Geronimo restaurant, and the practically vertical Sheldon Parsons residence near the foot of Cerro Gordo Road. These places were also packed like subway cars with people like me who paid five dollars for a ticket, a fantasy, a donation to a good cause. Next year, I bet, the Historic Santa Fe Foundation could charge $10 without the slightest drop-off in sales. Maybe the quirkiness of Santa Fe has been flattened forever by money and bad taste, but there is no shortage of dreamers longing for a glimpse of more interesting times.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Electromania 5

A couple of weeks ago on bloggingheads.tv, I was telling my colleague John Horgan about my trip to the Sandia Crest antenna farm to see if I would get a headache from the microwaves. Bill Bruno, the Los Alamos physicist and anti-wireless crusader, had proposed the experiment in a comment he appended to this story in the New Mexican. Try as I might I could not detect any aftereffect. The reason, Arthur Firstenberg (the other big Santa Fe wireless foe) told me in an email is because weaker levels of microwaves are, paradoxically, more harmful than stronger ones. Electromagnetic homeopathy!

During my discussion with John, I placed my own cellphone on top of my microwave meter and asked him to give me a call. (You can watch the video here.) As in previous experiments, the needle leapt to the top of the scale before reclining. The gyrations may look alarming on camera, but what I was measuring was a minuscule amount of energy flux. Then again, the Firstenberg effect would predict that the greatest danger comes when the needle hardly moves at all.

I was reminded of all this on Monday afternoon when the long-delayed Interphone study, the largest yet on the epidemiology of cell phones and brain cancer, was finally published. More than 5,000 brain tumor patients in 13 countries were asked to recall in detail how often they had used their mobiles during the last 10 years. Then the data were compared against those of a symptomless control group.

The results were so murky that for four years the researchers argued over the meaning. In the end, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded, as has almost every previous study, that there is no correlation between the amount of time spent talking on a cell phone and brain cancer. In fact, weirdly enough, regular users had a lower risk of getting brain cancer than people who didn’t use cell phones at all. Maybe the phones were acting, through some spooky new physics, as handheld radiation therapy machines, nipping tiny malignancies in the bud. More likely, the authors concluded, the result is an artifact caused by unreliable data, sampling bias, or random error.

There was also another puzzling anomaly: Among people who reported that, over the years, they had spent as much as 12 hours a day (!) with a phone against their ear, the risk of a tumor called glioma jumped all of a sudden by 40 percent. Or so it appeared. Maybe people with brain cancer, desperate for an explanation, were prone to overestimating the severity of their cell phone habit. Maybe their memory or their reason was impaired by the tumor. When you dig into the details, there was so much room for error that it’s questionable whether the study was worth the $25 million cost.

Even if the effect should turn out to be real, it begs to be put into perspective. Glioma is exceedingly rare. A person’s odds of being diagnosed with the cancer is one in 30,000 or 0.0033 percent. A 40 percent increase would make that 0.0046 percent

“If there was a large and immediate risk we would have seen it,” Anthony Swerdlow of the Institute of Cancer Research told Clare Murphy of BBC News.

Whether it is worth doing more research, that is a question for society [he continued]. These are expensive studies, and there are many other things in the world that should be investigated. It is society which has to answer the question of how long you continue to investigate something that does not have a biological basis.

In fact another, even bigger investigation is already under way. The Cohort Study of Mobile Phone Use and Health, or COSMOS, plans to monitor 250,000 volunteer cellphone users for 30 years. Final results are due in 2040. Please stay tuned.

Related posts: The Electromania Archives

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Science Fiction

Crystals and Black Lights at the Santa Holistic Fair

On the way to the outlet center in search of some cheap Hawaiian shirts, I was punching buttons on my car radio — Sunday morning on the airwaves can be pure hell — when I alighted on KBAC’s weekly three-hour infomercial, Transitions Radio Magazine. The mellow hosts (“your whole brain radio team”) were enthusing about Dr. Leva Wright, a holistic dentist who promises to readjust your energy meridians to give you a healthier mouth and soul. Each tooth, you see, resonates with a different bodily organ. Your eye tooth with your liver — everything is connected.

Next came an endorsement for “zero-point” technology: “Imagine detoxifying water as well as returning its life force and promoting the health of plants and pets with a tricorder-like device as on Star Trek. Yes, it exists. It can be proven . . . I have one in my right pocket.”

I was about to jump over to KUNM, hoping that the hour-long Indian chants had not yet begun, when there was an advertisement for the Santa Fe Holistic Fair (“the place to clear your chakras and aura and learn about earth changes as we head for 2012.”) It was happening at that very moment at the Santa Fe Railyard, a detour I couldn’t resist.

I was about to jump over to KUNM, hoping that the hour-long Indian chants had not yet begun, when there was an advertisement for the Santa Fe Holistic Fair (“the place to clear your chakras and aura and learn about earth changes as we head for 2012.”) It was happening at that very moment at the Santa Fe Railyard, a detour I couldn’t resist.

It cost $5 to get inside where rows of New Age carnies were plying their wares: kirlian photography (for capturing images of your aura), reflexology, kinesiology, biomagnetic healing, angelic channeling. There were psychics and crystals galore. The mix of magic, esoterica, and quackery wasn’t much different from what I first encountered as a reporter in Minneapolis many moons ago. As science advances, the wisdom of the ancients remains stubbornly unchanged.

A woman from Colorado was selling Salt Lamps, “powerful natural negative ionizers that rid the air of dust, pollen, and bacteria, and neutralize EMF waves emitted by electronic devices.” The perfect remedy for those cell phone headaches. The Richway Amethyst Bio-Mat healed with “Far Infrared Ray technology” (also known as heat), while at the other end of the spectrum the BleachBright lady whitened your teeth with a shining blue light and (the active ingredient) hydrogen peroxide paste. (I was surprised to learn later that light near the ultraviolet range can indeed be a catalyst for oxidizing reactions, but I suspect that the BleachBright lamp was there just for show.)

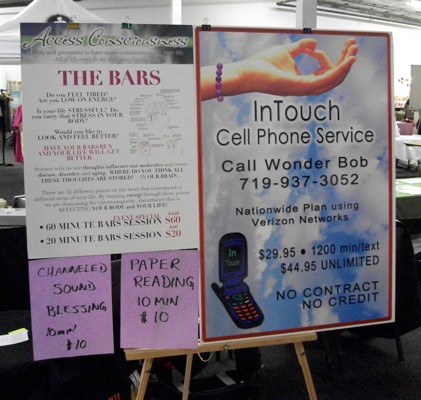

With the vendors outnumbering the customers, Wonder Bob (Soul Guide, Spiritual Coach, and facilitator of Infinite Consciousness) was running a special: 10 dollars for 10 minutes of Channeled Sound Blessing and $60 for an hour-long “bars session,” which sounded like a new plan from Verizon. Coincidentally Wonder Bob was also a sales rep for something called InTouch Cell Phone Service, and I imagined at first that his two businesses were connected. Every day when the moon and stars were in proper alignment, Bob (or maybe his computer) would send a signal to your mobile perfectly modulated to sooth your brain.

The actuality was less interesting. “There are 32 different points on the head that correspond to different areas of your life.” (Those are called “access bars,” and I bet they also correspond to each of your teeth and organs.) “By running energy through these points we are dissipating electromagnetic disturbance that is AFFECTING YOUR BODY and YOUR LIFE!”

Some people might read all this and say, Oh that is sooo Santa Fe. But it’s not. Like the old traveling medicine shows of the Wild West, these New Age carnivals move from town to town, preying on the hopeful, the credulous, and the just plain stupid. The Santa Fe event was the work of a Colorado promoter called Alternative Change Productions, which had just organized a similar show in Casper, Wyoming.

Though few outsiders know it, Santa Fe is better distinguished as a city of science. At the Santa Fe Institute physicists, biologists, anthropologists, and computer scientists confer with one another — and with their colleagues nearby at Los Alamos (which does far more interesting things than bomb making) and the School for Advanced Research. Throughout the year these institutions offer a lineup of public lectures unmatched anywhere. Through its Science Cafés, the Santa Fe Alliance for Science brings the intellectual excitement to the schools. We have The Santa Fe Complex and The National Center for Genome Resources.

As I write this, 46 students and five instructors from all over the country (and from Canada and the United Kingdom) are arriving in town for the annual Santa Fe Science Writing Workshop, which my colleague Sandra Blakeslee and I started 15 years ago. Wednesday evening beginning at 5:45 p.m., some of us will be giving a public reading at Collected Works Bookstore.

Maybe all these efforts are paying off. Attendance at the Holistic Fair was sparse. Two men with towering turbans chatted in the deserted lunchroom where the organic buffet went begging. Sitting at a card table, a woman dressed like a gypsy stared into space waiting for a fortune to tell. In an anteroom a psychic named Tallkat was giving advice on “Talking With the Dead.” The next step will be figuring out how to charge their credit cards.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review