California Pastrami, West Alameda Street. photos by George Johnson

Mr. Coss’s Second Term

The day before the city elections, a reader who is a realtor with Sotheby’s told me what she thought about my final dispatch in last month’s issue. “You’re right about one thing,” she said. “If enough people pull the lever for Mr. Coss, we will have more of the same.” She didn’t mean that as a good thing, but her words got me thinking: Would it really be so bad? As mayor, David Coss has done more than anyone at City Hall to support river restoration, and he was crucial in striking the deal to keep the College of Santa Fe, an important cultural resource, from closing. He has given dependable support to affordable housing and Santa Fe’s minimum wage — noble efforts to keep this place from becoming another Aspen.

Then I picked up the newspaper on election morning to see that he had received a last-minute $5,000 donation from Andrew and Sydney Davis, the immeasurably wealthy couple who maneuvered around Santa Fe’s land use laws to build their castle in the sky, a sad monument to the city’s failure to protect its scenic ridgetops.

How far Mr. Coss has strayed from his roots. Five years ago when the Davises wanted to close off and gate the public street that leads to the mansion — the project was just getting under way — Mr. Coss, who was then a city councilor, showed no sympathy: “I think they’ve basically manipulated the escarpment ordinance to build a trophy home that the rest of us have to look at,” he told the New Mexican. A few months later the Davises sought revenge by contributing $10,000 to David Schutz, the land developer who was opposing Mr. Coss in the 2006 mayoral election. Now the Davises are on board the Coss bandwagon, as is Mr. Schutz himself, who also donated to the mayor’s reelection.

The same thing, of course, happened with Garrett Thornburg. As a councilor Mr. Coss questioned Mr. Thornburg’s plans to plop down his corporate “campus” in the middle of a northside neighborhood. Mr. Thornburg retaliated by supporting Mr. Schutz. But when it came time to shell out for the 2010 campaign, he too had become a believer, another of Mr. Coss’s influential new friends.

I guess you can call that building bridges or loving thy enemy. But inside the voting booth, it didn’t sit right with me. I pulled the lever (o.k., darkened the oval — I miss the old voting machines) for Miguel Chavez, knowing Mr. Coss would go on to win by a landslide. I still think he is the best mayor Santa Fe has had in awhile. The bar was set pretty low. What he lacks and maybe still can gain is a vision, something bolder than his slogan un lugar para todos, or, roughly translated, Can’t We All Just Get Along?

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Electromania 3

After I wrote last month about the misrepresentations of the electrophobes (please see Electromania Part 1 and Part 2), I heard from Bill Bruno, the Los Alamos physicist who is a leader in the fight to banish all things wireless from within the city limits. I asked him to give me his best shot, the five or so papers that present the strongest case for the health hazards of cellphones and wifi. I wasn’t interested in petitions by concerned citizens or anecdotal cases (the child screaming in the night when the wifi is switched on) or conspiracy theories, but solid, peer-reviewed science.

He referred me first of all to Salford 2003, which I wrote about here last month, and noted that there was a followup study involving more rats. The problem again is whether the “dark neurons” that were reported really represent brain damage and whether they were caused by microwaves or by scooping the rats’ brains out, slicing them like baloney, and infusing them with chemical stains for observation under an electron microscope. In a review article, the researchers themselves note that while one laboratory in Turkey got similar results, three others in the United States, Japan, and France have failed to replicate the experiment. Other studies from the Salford lab have suggested that microwave radiation may cause leaks in the protective blood-brain barrier. But the findings are called into question by the puzzling conclusion that lower levels of microwaves appear to produce more leakage than higher levels do. Other studies have found no effect at all.

From Arnetz 2007

In the next paper Mr. Bruno cited, Arnetz 2007 (The Effects of 884 MHz GSM Wireless Communication Signals on Self-Reported Symptoms and Sleep), volunteers took turns wearing a helmet-like contraption that held a microwave transmitter a few inches from their heads. Subjects who were exposed for three solid hours to microwaves of about the intensity of those emitted by a cell phone took six minutes longer to fall asleep than the control group, which received a “sham” exposure. They also experienced an average of 8 minutes less of the deepest kind of sleep, called stage 4.

It’s curious that anyone could sleep at all under such circumstances. The paper refers obliquely to “sleep initiated one hour after exposure” without saying what did the initiating. Sleeping pills or a hypnotist’s dangling watch?

The second part of the Arnetz experiment is even murkier. About half of the 71 subjects considered themselves electrosensitive — they blamed cellphone emanations for various health complaints. But the study found that they were no more likely to experience headaches from microwaves than from the sham exposures. Confusingly, the nonsensitives did report more headaches. The authors don’t supply the numbers, making the outcome impossible to judge. During the exposures the subjects were also given memory and performance tests and questioned about their moods. These results were not reported, presumably because they weren’t significant.

The third paper on Mr. Bruno’s list was Bise 1978, which reported that extremely low intensities of radio waves and microwaves — far below what existed even back then in urban areas — caused “temporary changes in brain waves and behavior” in 10 subjects. The experiment, which has gone unreplicated now for 32 years, was done by William van Bise, a researcher into the paranormal who might have served as a model for Walter Bishop, the mad scientist on the TV drama Fringe. During the early 1990s an eccentric R.J. Reynolds tobacco heir apparently invited Mr. van Bise and his wife, Elizabeth Rauscher, to use his estate in North Carolina as a research center for something called “psychotronics.” (The story appears in bits and pieces scattered around the Web.) They were joined there by Andrija Puharich, a champion of the psychic Uri Geller, who claimed to bend spoons with his mind. All were evicted after their benefactor died.

The rest of what Mr. Bruno presented me with didn’t involve cell phone radiation but rather the lower frequencies from power lines and broadcasting stations: Historical Evidence That Electrification Caused the 20th Century Epidemic of “Diseases of Civilization” by Samuel Milham has been countered in a rebuttal by Frank de Vocht, a lecturer in Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Manchester, who called the work “fatally flawed.” A study from Finland reported that TV and FM radio signals focused by a reflecting wall caused spontaneous hand movements in a few subjects. Finally Mr. Bruno mentioned the work of Martin Blank, an associate professor at Columbia, who has reported that low frequencies might induce a stress reaction in cells. Again this is a controversial view.

So we are still at square one with a minority of much-disputed reports suggesting that a whole range of electromagnetic radiation might possibly have subtle biological effects, which may or may not be harmful. If your aim is to dismantle the wireless communication structure of the planet, including radio and television, along with the worldwide electrical grid, that is not very much to go on.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Santa Fe’s New Telecom Law

Though the City Council wasted a lot of time last month listening to histrionic claims about health effects of wireless technology, there were good reasons for the postponement of the vote on a new telecommunications ordinance. While municipalities cannot override the federal government in setting standards for electromagnetic exposure, they do have the power to make sure that companies, like the ones vying to install underground fiber-optic Internet lines and small antennas downtown, abide by land use laws, including those that protect historic districts. The new draft that the council will consider tonight goes a long way toward addressing those issues (particularly with the additions, highlighted in red, starting on page 39).

I was surprised, however, that the latest provisions are not as strict as those in Albuquerque’s wireless ordinance (which, confusingly, is separate from its code for wired utilities). In Santa Fe above-ground equipment like antennas “shall be designed, installed and maintained in such a manner as to minimize the visual impact.” In Albuquerque wireless equipment must be “concealed,” and there are several paragraphs specifying exactly what that means.

Old Power Lines in an Ice Storm (stock photo)

Both cities impose additional burdens within historic districts. In Santa Fe telecom equipment must be approved by the planning department’s historic preservation staff. (In an earlier draft, a hearing by the citizens’ Historic Review Board was required, but that may be overkill.) Albuquerque mandates that wireless installations in historic neighborhoods be both concealed and “architecturally integrated.” Antennas are banned altogether from the center of Old Town (probably a violation of federal law), and any neighborhood association, historic or not, has the right to be consulted about antenna design.

As a resident of one of Santa Fe’s oldest neighborhoods, I don’t want to be shut out of the next stage of the information revolution (it takes far too long to download a high-resolution episode of Caprica), but maybe our recommended regulations for antennas need a little more tightening.

I was especially impressed by the requirements Albuquerque wrote into its agreements with Brooks Fiber and with CityLink, providers of underground optical data lines. A certain amount of unused cable or “dark fiber” (not to be confused with dark neurons) must be reserved for use, free of charge, by the citizenry — local government, the convention center, public schools, and colleges. It will be a few weeks before Santa Fe can start approving franchises under its new code. But it is important to ensure that it has the power to make similar demands.

In yesterday’s New Mexican John M. Brown, the president of CityLink, ranted about Santa Fe’s proposed $2,500 application fee and a requirement to notify neighbors living along rights-of-way. The proposed ordinance is so burdensome, he fumed, that Santa Fe customers would have to pay 2 1/2 times as much as they do in Albuquerque for the privilege of doing business with him.

CityLink CAN NOT accept this [he shouted in an email to reporter Tom Sharpe] and unless changed will NOT be servicing Santa Fe anytime soon.

Then good riddance. His competitors will be lining up at the door. Albuquerque also charges $2,500 to apply for a franchise, and for wireless providers the fee is $3,500. From what I can tell from the Albuquerque code, neighborhood notification is less stringent and is required only for wireless. So there still may be more tinkering to do before the Council’s final vote. But overall Santa Fe’s proposed regulations are far more streamlined and clear than Albuquerque’s and should help put us on the map — and in the world economy — as a great place from which to telecommute. Meanwhile I urge my readers, including those at City Hall, to nominate Santa Fe as a participant in Google’s Fiber for Communities program. The deadline is approaching fast.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Postscript to the Telecom Tales

The New Mexican’s Tom Sharpe has done a reasonably good job this week untangling the issues in the proposed new telecommunications ordinance, but I winced when I saw that he was planning to devote a full day of his series to the “health effects” of electromagnetism. The paper has embarrassed itself before by taking wild assertions from self-proclaimed experts at face value and doing little or no fact checking. We get much of the same this morning.

Before approving publication of the story, an editor should have insisted on a prominent paragraph noting that the majority of biophysicists, epidemiologists, and research oncologists who have studied the matter find no reason to believe that the low-level microwave radiation from cellphones or wifi is worrisome. But it’s Mr. Sharpe’s second article that is so dreadful that I feel like using it this spring at our Santa Fe Science Writing Workshop as an example of how not to cover a complex issue.

After giving a fringe group an open mike, the New Mexican had a responsibility to focus on what the science really says. Instead we get a profile of a local “healthy home” consultant, Daniel Stith, who concedes that his evidence about the supposed dangers of wifi (and a slew of other things) is “more anecdotal … versus some kind of study.” We also hear from someone named Vicki Warren, who teaches courses on “electrosmog” and is allowed to go on for seven paragraphs reeling off misinformation that could have easily been checked.

It is not enough to counter all of this propaganda with some quotes from a Motorola spokesman. This “he says, she says” approach is lazy journalism that creates the false impression that science is simply a matter of opinion, and that there are two equally weighted sides to every story.

Related Posts:

Electromania at City Hall

Electromania, Part 2

Electromania, Part 3

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Bad Infill

A long-standing theme here at The Santa Fe Review is how the city’s developer-friendly land-use laws have been slowly eroding the character of the older neighborhoods. It’s far too easy, even in the historic districts, to split off part of an already occupied lot and build another house to sell. (Please see Sorrows of San Acacio for an account of what has happened on my own street.) After the division, the owner of each lot, the old one and the new, has the right to build not one but two houses — a main house and an “accessory dwelling,” or guest house, which can be converted into a commercial vacation rental.

It was only after reading an eye-opening piece in Sunday’s Journal by Karen Peterson that I realized the situation is even worse. The “accessory dwelling” can be as large as 1,500 square feet, which in some cases is as big or bigger than the “main house.” And without any say from local officials it can be turned into a condominium and sold separately. Where once there was one residence, now there are four. Condominiums, it turns out, are regulated not by the city but by the state.

Former city councilor Karen Heldmeyer led the Journal on a tour of what one resident, Pete Garcia, called “infill gone wild.” The result is must reading for anybody who cares about what the real estate speculators are doing to this town.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Stewart Udall

It is cause for celebration when someone lives to be 90 and remains intellectually vibrant and politically alive. Yet it was sad to read that Stewart Udall has died. Shortly after I moved here in the early 1990s, I interviewed him for a piece I was writing for the New York Times about Indians and environmentalism. (This was when Pojoaque Pueblo was threatening to open a nuclear waste dump if it didn’t get its way on tribal gambling.) A few months later, when Fire in the Mind was published, I sent Mr. Udall an invitation to my book party — he lived just up the hill — and was delighted when he appeared at the back door. Here was the former Secretary of Interior under the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, a man who had expanded, through sheer force of will, the National Park System and helped push through the Wilderness Act, and he was standing in my kitchen offering a toast before heading home to watch a football game.

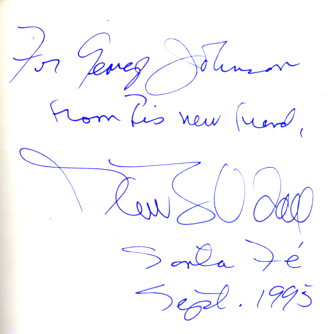

Stewart Udall book inscription

Once or twice, on his walks around the neighborhood, he dropped off an envelope addressed “Hon. George Johnson” with information about a story he thought deserved attention. He also gave me an inscribed copy of The Myths of August, his book about the fallout — figuratively and literally — from America’s conduct in the Cold War.

In another epic standoff, he was instrumental in dissuading the actress Shirley Maclaine from building a mansion near the top of Atalaya Mountain. A few years later when an investment banker, Paul Tierney, sued the City of Santa Fe for denying him permission to build on another hilltop (the site of the old Talaya Reservoir above Camino San Acacio), I took my Times colleague James Brooke to meet Mr. Udall. Jim, a national correspondent based in Denver, was writing about the controversy and I figured Stewart would have something interesting to say. As the three of us stood on a ridge behind the Udall compound, off Camino de Cruz Blanca, the former Secretary lamented how ostentatious trophy houses were springing up in defiance of Santa Fe’s modest ways.

“Vail, Aspen, Telluride, Jackson — those are communities with different histories,” he said. As he looked northwest toward the Tierney hill, he noted that it was as prominent as “a prow of a ship — the last hillside site within the inner city. For him to do this right in the middle of the city violates everything that Santa Fe is about.”

It was a losing battle. Mr. Tierney prevailed in his lawsuit and sold the lot to Tom Ford, whose mansion, an even bigger one, is almost complete.

Related Posts:

Part 1. A Stroll Along Shirley Maclaine Boulevard

The Battle for Talaya Hill

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Tom Udall and the Indian School

I don’t know what Stewart Udall thought about the All Indian Pueblo Council’s secretive and almost surely illegal decision to demolish (in collusion with sympathetic officials at the Bureau of Indian Affairs) the historically significant campus of the Santa Fe Indian School. (Here is the background for those new to the tale.) Throughout his career, the elder Mr. Udall focused less on preserving buildings than on preserving land. Fair enough. But I fear that his son Tom, New Mexico’s newest United States Senator, may treasure political expediency and political correctness over investigating substantial allegations of federal misconduct.

On March 5, I sent him this fax:

Senator Tom Udall 110 Hart Senate Office Building Washington D.C. 20510 Dear Tom, On October 8, 2009, I received a phone call from a member of your Washington staff, Raven Murray, who was following up on a letter I sent you on June 8 regarding my request for an Interior Department investigation of what appear to be clear and deliberate violations of the National Historic Preservation Act in the demolition of the historic Santa Fe Indian School campus. (The details are described in the enclosed copy of my letter to the department dated September 25, 2008.) Ms. Murray said she had been in contact with Interior and had been assured that a legal opinion from the Inspector General's office was forthcoming. I've heard nothing since. It has now been a year and a half since I first contacted Interior about this matter. I am asking that you again inquire about the status of the case. Thank you very much.

There has been no response.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review