View from Gregg Avenue, Santa Fe, N.M. photos by George Johnson

Last Stand at Paolo Soleri

Midway through May, a page appeared on Facebook imploring the secretive administrators of the Santa Fe Indian School not to tear down the Paolo Soleri amphitheater. Day after day, heartfelt testimonials poured in from students and alumni sharing memories of graduation ceremonies at the Paolo (the most recent was on Friday) and the mind-blowing concerts they attended there.

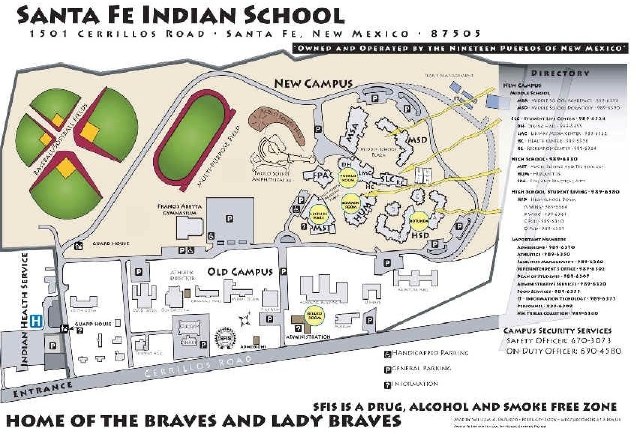

Santa Fe Indian School, May 30, 2010

The possible demolition is a rumor, but there are good reasons to fear that it is true. As readers of my past installments know, school officials have already flattened — with no warning or consideration for anyone’s feelings but their own — the beautiful old buildings of the historic campus, and they have cut down a forest of old shade trees. What happened was illegal. The only question is whether it is the Bureau of Indian Affairs or the All Indian Pueblo Council that is to blame. Possibly they acted in collusion. Whoever is responsible has gotten off scot-free. (For a condensed version of the legal issues, please see my letter of September 25, 2008 to the Interior Department.)

With the new public Facebook page, some of the school’s former students — who were as shocked as anyone when the bulldozers rolled in — finally have a forum for expressing their sorrow. Here is how Audrey Archuleta of Española put it:

After what they did to the trees on that campus, this is not surprising. Whoever is making these decisions should be ashamed of themselves. What else can you say? Every time I pass by that campus now it makes me angry, ashamed, and sad all in the 60 seconds it takes to drive by.

This is from Lisa Elkins of Thoreau, New Mexico, at the edge of the Navajo Nation:

My mom grew up on that campus. It was a shock to come home and find that they destroyed that school, NO TREES, NO HISTORIC buildings. It was a crying shame! Now this??

Norma C. Romero, a member of Taos Pueblo, wrote about the sadness she felt over how the campus has been laid bare and turned into a dust bowl:

Paolo Soleri is our last stand. Our Grandparents and many generations have put the foot markings on the ground on which it stands. What has become of the pride we all each held? This is a sad day not only for me, but thousands who share the same feelings.

So where is one to turn? The Old Santa Fe Association and the Historic Santa Fe Foundation have been too timid to demand an investigation. Withering under political pressure, the New Mexico State Historic Preservation Office (called the SHPO) failed to intervene. Within the SHPO’s office I know employees who are sickened by what was allowed to happen on their watch. But they are afraid to speak out lest they lose their jobs. I don’t know what I would do in their situation.

In theory, both the BIA and the SHPO are within the jurisdiction of the Interior Department, whose Inspector General, Earl Devaney, is required to investigate allegations of crimes. He apparently can’t be bothered. Yesterday in reply to my latest inquiry, I heard from one of Mr. Devaney’s assistants, Scott Culver. His title is Deputy Assistant Inspector General. One of his functions is apparently brushing off people who inconvenience his boss by asking that he do his job.

Here is Mr. Culver’s nonresponse to my letter:

We understand this issue has been raised with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the State of New Mexico Office of Cultural Affairs -- Historic Preservation Division, which are the appropriate forums for your complaint. Thank you for contacting our office.

What a classic run-around. I originally wrote to the Inspector General in September 2008 after being stonewalled by the BIA and after the New Mexico SHPO dropped the matter like a hot potato. So I appeal to the next level of the hierarchy, the Inspector General, and after repeated inquiries am referred by Mr. Culver back to the very culprits I am complaining about. He obviously read none of the supporting documents I submitted.

Through his own inaction, Senator Udall has been as complicit in the cover-up as Mr. Devaney. (Here is my latest letter to the Senator’s office.) Given this stalemate, the only recourse would seem to be the Justice Department. Hence this other letter I recently sent to Kenneth Gonzales, the new United States Attorney for New Mexico. Though not a tribal member, Mr. Gonzales graduated from high school in Pojoaque and worked for Senator Bingaman on Indian affairs. Will he be sympathetic to the politically powerful Indian Council or to the pueblo people whose memories have been destroyed?

Just like the buildings that were razed in 2008, the Paolo Soleri, named after the Italian-born architect and built by students from the Institute of American Indian Arts, was listed in 1989 as a “historically contributing” building because of its Neo-Expressionist architecture. (The details are in a 1989 document titled “Santa Fe Indian School Historic District,” by Sally Hyer. I have posted it in two parts: A description of the buildings and Historical context.)

It is still possible that the Paolo Soleri can be saved. It is also still possible that the bureaucrats who destroyed the rest of the old campus can be brought to justice. But nothing is likely to happen unless the impassioned souls who have flocked to the Save Paolo Soleri Facebook page demand to be heard.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Postscript

Digging through my files this morning on the Santa Fe Indian School, I see that one of my earlier communications with the Department of Interior, dated March 11, 2009, was also with Scott Culver. He assured me that his office was reviewing the matter and “will inform you of the disposition of your complaint.” Of course that never happened. I waited three months and then contacted Senator Udall on June 8, 2009. Four months after that I got a call from one of his staffers, Raven Murray, assuring me that they were pressing the matter and that Interior had assured the Senator’s office that a legal opinion was forthcoming. All that, it seems, was smoke and mirrors.

Paolo Soleri, Part 2

In this morning’s Journal, Kathaleen Roberts writes that the Paolo Soleri Theater “was considered for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places” (which would have afforded it Federal protection) but that “the effort fizzled.” What happened was much worse.

In 1994, some two dozen buildings on the old Indian School campus — apparently including the amphitheater — were deemed eligible for the historic register. That is an important distinction. Whenever Federal funds are involved in a project, Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act gives eligible buildings the same regard as those that have already been admitted to the list: strict procedures involving public disclosure and consultation with other agencies must be followed before the buildings can be destroyed.

If eligible buildings are “transferred, leased, or sold out of Federal ownership or control,” then Interior Department regulations (36 CFR Part 800 — Protection of Historic Properties) require that “adequate and legally enforceable restrictions or conditions” be put in place “to ensure long-term preservation of the property’s historic significance.”

As we’ve written here before, the Bureau of Indian Affairs violated Federal law by failing to include those provisions when it handed over the school to the All Indian Pueblo Council. (Again please see my original letter to the Inspector General of Interior for details.) This may be more than a matter of negligence or incompetence. If officials within the BIA ignored the requirements while knowing of the Pueblo Council’s secret plans to raze the campus, they may also be guilty of conspiracy to circumvent the law. This is what I have been trying to get the Inspector General of the Interior Department to investigate.

If the leaders of the Pueblo Council now plan to put the Paolo Soleri on the chopping block, a good time to watch for the wrecking cranes will be some dark night in July. That is when the Pueblo Council has indicated that it will tear down the Academics building, which was constructed in 1962 in International style and has been leased recently to the Tierra Encantada Charter School. A second International-style structure, the Administration building, will probably also be leveled then, along with the U-shaped Arts and Craft building, which was designed and built by John Gaw Meem in 1931 and earned him his commission to remodel the rest of the school in the same Spanish Pueblo Revival Style.

Of these buildings, only the third is on the eligible list. Here is how it was described by Sally Hyer in her report, “Santa Fe Indian School Historic District”: “This building faces on the main campus walk and is surrounded by spruce, elm, and poplar trees and a grassy lawn.” No longer. It is the same building pictured in the forefront of the photograph I posted in yesterday’s installment, a barren wasteland of weeds.

Related posts: A Special Report: The Mysterious Destruction of the Santa Fe Indian School

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Postscript

I just heard from a staff member at the Indian School that the demolition of the Paolo Soleri is a done deal.

Supposedly they will issue a press release one of these days . . . Apparently the Board of Trustees is behind the decision and they have an architectural image of what the "new" campus should look like . . . We have a meeting in the morning. Not sure if the Paolo will be addressed, but I would say the majority of the staff is against the demolition.

Not that it will make a difference. The Pueblo Council runs the tax-supported school as though it were its personal fief.

Indian Ruins

After my latest round of correspondence with local preservationists, the status of the Paolo Soleri seems less certain than it did when I wrote yesterday’s dispatch. The historian Sally Hyer indeed included the amphitheater in her 1989 survey of 28 historically significant structures on the Indian School campus. Five years later the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the New Mexico Historic Preservation Office concurred that many of the buildings were eligible for Federal protection. The question is whether the Paolo Soleri was among them. I hope to know the answer soon.

Unfortunately, it may not matter. The amphitheater’s status would be as a “contributing” structure to the Santa Fe Indian School Historic District. But there is no longer anything to contribute to: the Historic District was wiped out in 2008 by the Pueblo Council. Whether it would do any good to seek eligibility for the Paolo Soleri as freestanding architecture is also unclear. The Pueblo Council takes its money from two pots: casino proceeds and Federal grants. Unless the latter pays for the destruction, Section 106 protections would not apply.

From what I have learned in recent days, there is little doubt that the BIA was fully aware that the Pueblo Council planned to destroy the campus as soon as it gained control. Yet the property was transferred from Federal protection without the covenants required by law. What the Inspector General (or failing that the U.S. Attorney) should be investigating is which officials were responsible and whether there was some kind of deal.

I was reminded today by Zane Fischer’s column in the Reporter, Soleri Eclipse, about the blueprints he uncovered last year for what appears to be a huge commercial development to rise from the ruins along Cerrillos Road. Before that can happen the three remaining buildings described here yesterday must be removed, including what may be the most historically significant of them all. As Mr. Fischer notes, these are blocks away from the Paolo Soleri, but maybe the Pueblo Council’s demolition contractor, Flintco, has offered the school a package deal.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

“Leaders”

I never went to a concert at the Paolo Soleri. My memorable sonic experiences were at lesser venues in Albuquerque: Johnson Gymnasium at the University of New Mexico where Joni Mitchell was backed by Allen Ginsberg and Stewart Brand on cymbals and drums (or were those two different occasions?) The New Mexico State Fairgrounds where my auditory nerves were seared by Steppenwolf, Three Dog Night, and Canned Heat. UNM’s bottomless Pit, where I took my high school girlfriend, Dawn Wagner, to see Simon and Garfunkel.

Later on when I was covering the crime beat for the Albuquerque Journal, I called-in sick and escorted my colleague Susan Landon (long dead now from ovarian cancer) to the same auditorium to see Fleetwood Mac. There was a ritual then (still?) of lighting matches in celebration of the music. My mind inflated with second-hand whiffs of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, I watched as the random flarings locked into stair-step constellations while Stevie Nicks — I was in love with Stevie Nicks — gyrated down on the microscopic stage. Order out of chaos. Or something like that.

It is remarkable how evocative musical memories can be. Hence the loud chords of protest struck by the rumors of the Paolo Soleri’s impending destruction. Wednesday night, I am told, the Marley Brothers performed there, proclaiming that the concert would be the Soleri’s last. They played Leaders leaving behind the implication that the leaders of the Santa Fe Indian School are betraying the people who have entrusted them to make wise and honorable decisions.

The outcry over the Paolo Soleri is but a fraction of what would have ensued if the All Indian Pueblo Council had acted forthrightly in 2008 and disclosed what it had long intended for the historic campus. A brave investigative journalist might uncover whether these “leaders” acted solely according to the school’s best interest or whether any of them also stand to benefit financially from the hotel-museum-strip mall — whatever is secretly in the works.

So many questions have been allowed to go unanswered. Just who runs Flintco, the Native-owned company that is billing the Indian School for demolition and construction? Has anyone in the outside world monitored the bidding process or Flintco’s performance or looked for conflicts of interest? Has anyone audited the books and determined that no Federal money was used to tear down the buildings?

At a higher level of the hierarchy, are Earl Devaney, Scott Culver and the other Interior Department functionaries who are letting these matters slide merely overworked or apathetic — or under pressure from Senators Udall and Bingamen, who look to the Pueblo Council to deliver votes? Have they too confused the interests of the leaders with those of the led?

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

The Paolo Soleri’s Last Hurrah

Finally after all the speculation, the rumor is confirmed. This morning the superintendent of the Santa Fe Indian School, Everett Chavez, publicly announced (on, of all places, 94 Rock’s Morning Show ) that the Paolo Soleri amphitheater will be destroyed as part of the school’s “aggressive educational agenda.” (You can find an audio link to the interview at the top of this page.)

Cutting through the typical talk radio banter, Mr. Chavez sounded like a thoughtful and intelligent man. The Paolo Soleri costs $95,000 to $99,000 a year to maintain, he said, and it would cost $578,000 to bring it up to code, which would include compliance with the Americans With Disabilities Act. Last week’s concert, he said, took in only $5,000.

After the show, he added, there were beer bottles all over the place, and one of the 19 Pueblo Governors remarked about the miasma of marijuana smoke — a “huge cloud of illegal stuff.” That, Mr. Chavez said, is not the kind of behavior they want to instill in their students. A better place for concerts, he insisted more than once, is the Indian casinos.

All of that begs the question, finally asked by one of the DJs: But why do you have to bulldoze the place? Why not find someone to take over and upgrade the venue? Rather than giving a straight answer, Mr. Chavez played the spiritual card.

“Our people are taught not to get attached to material things,” he said. He remembered when the kiva at his pueblo had to be replaced because the population had grown. And there was the time that his father (like his grandparents, an Indian School alum) refused to give him an old pickup truck he loved. It was traded in for a new one instead.

Likewise the Paolo Soleri now must be traded in for — for what? Mr. Chavez wouldn’t say.

He added that there will be three or four more events before the demolition, including a tribute to Stewart Udall, the former Secretary of Interior and friend of the school, who died this spring. How politically astute. Mr. Udall was, of course, the father of Senator Tom Udall, one of the few people with the clout to put a stop to this — and to demand a resolution of the legal questions still surrounding the earlier destruction of the old campus.

Instead the Senator will be there at the Paolo Soleri for a last hurrah, smiling and shaking hands, pretending that being friends with a few powerful Indian leaders is the same as being a friend to the people they rule.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Postscript

Updated June 9, 2010

After yesterday’s announcement by Superintendent Chavez, some contributors to the Save the Santa Fe Indian School Paolo Soleri Facebook page have wondered whether the soon-to-be-demolished structure will be replaced by a gambling casino. The same question arose after the illegal destruction of all those old John Gaw Meem buildings in 2008. The answer seems to lie in Sections 821 to 824 of a document called the Omnibus Indian Advancement Act of 2000, Public Law 106-568, 114 Stat. 2868:

(d) GAMING. Gaming, as defined and regulated by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (25 U.S.C. 2701 et seq.), shall be prohibited on the land taken into trust under subsection (a).

I am told that Senator Udall can be thanked for insisting on that provision.

This was the legislation that turned the Indian School campus, built and maintained over a century with millions of federal tax dollars, into an Indian Reservation, beyond the reach of city or state control. The act requires that the campus and its lands “shall be used solely for the educational, health, or cultural purposes of the Santa Fe Indian School.” Would a strip mall or hotel whose proceeds went toward education meet that test? Probably so.

In any case, the three remaining buildings along Cerrillos Road will apparently not be demolished as soon as next month. KSFR reported yesterday that the Tierra Encantada Charter School, which leases one of the buildings, has now been asked to stay for another year. I was also interviewed for the report, Unanswered questions about Santa Fe Indian School, which has been posted online.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Senator Udall Bows Out

Much has been written here about the failure of the BIA to add legal safeguards before turning over the historic Santa Fe Indian School campus to the All Indian Pueblo Council. But the lack of those covenants doesn’t get the Council off the hook.

The new school was built with Federal tax dollars, so before ground was broken, an environmental impact statement was required. Prepared by a contractor called Marron and Associates in 2002, the report flatly stated that “no buildings will be razed.” (It would be interesting to know whether that included the Paolo Soleri.) The report, which is referenced in a letter from the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division to Robert B. Montoya and Bruce Harrill of the BIA, went on to specify the following:

All vacated buildings will be maintained to the extent they have been maintained in the past. A study will be made as to the best use of the existing buildings. This study will be coordinated with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the new Mexico Historic Preservation office.

Which, of course, didn’t happen. Without any consultation the old campus was destroyed. The new school, in other words, was built in violation of the very conditions under which it was approved. So many illegalities with no one being held to stand account.

Yesterday, in an interview with KSFR’s Dan Gerrity, Senator Udall made clear that he has no intention of intervening in these matters. In fact, the Senator’s response was so lackluster that the station is unsure whether it will even be broadcast. Bill Dupuy, the news director, has given me permission to post the recording. You can listen to it here.

The City Council Bows In

Though Mayor David Coss tried to talk them out of it, a majority of the City Councilors voted tonight to approve Patti Bushee’s resolution calling for the preservation of the Paolo Soleri. (Here is a glitchy video of the short debate.)

Generally these symbolic gestures have no teeth, but another of the resolution’s sponsors, Councilor Matthew Ortiz, added amendments that may give the city some leverage over the Indian School. Last year the Council passed an ordinance requiring other government entities — county, state, or federal — that are served by the city water system to abide by its zoning and land development laws. The ordinance, still untested, was inspired in part by the County’s insistence that its new courthouse was exempt from review by the Historic Board. But the larger point was to remind these occupying powers that they are part of our town and that their actions affect us all.

Speaking in support of the Paolo Soleri resolution, Councilor Rosemary Romero put it like this: “I don’t think this is adversarial. I think this is accountable. This is saying to the All Indian Pueblo Council, ‘You are part of our community.'” Whether they want to be or not.

Councilor Ortiz also referred to some deal struck by a former City Manager, Jim Romero, that evidently promised the school — nobody can find a copy of the letter — 43 acre-feet of city water for future expansion. Mr. Ortiz called for the agreement, which he finds of questionable legality, to be declared null and void. If the Indian School seeks approval for a commercial project, it would, like any other developer, have to acquire its own water rights and transfer them to the City

For Mayor Coss this all seemed so unfriendly. Wasn’t it enough that the school superintendent, Everett Chavez had “reached out” to him that very day? “Reaching out” meant agreeing to do lunch a few hours before the resolution was scheduled for a vote and then trying to forestall it. The superintendent (who has been governor of Santo Domingo Pueblo and who donated $1,000 to the Coss campaign) apparently reminded the Mayor that a city sewer line runs across school property and that the easement expired in 2003. Mr. Coss was impressed: “Telling them, ‘You can’t hook up to our sewer’ may be a hard statement to make when our sewer is on their land,” he argued.

In the end only Councilor Miguel Chavez sympathized, casting the sole vote against the resolution.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Frances Abeyta’s Fire

Roundhouse wall art

As I sat this afternoon in a meeting at the Roundhouse listening to Frances Abeyta’s tearful plea to the state’s experts on historical preservation, I wished it were 2008 when the old Santa Fe Indian School was still standing. The web page Ms. Abeyta started has brought the imminent destruction of the Paolo Soleri amphitheater to the world’s attention. Now the young woman, who grew up at the school, was asking the Cultural Properties Review Committee for help. If only she, or someone with her spirit, had learned two years ago of the secret plans that crushed the old John Gaw Meem buildings. Today’s hearing might have been about trying to save not just the Paolo Soleri but the whole campus. Its destruction, she said, has been heartbreaking.

As it turned out the committee didn’t need much persuading. “We’ve really worked hard with the American Indian community over the last couple of years in preserving what they thought were important cultural properties,” said Tim Maxwell, a prominent archaeologist. “I would like to receive the favor in return of their listening to us.” A resolution drafted on the spot by archaeologist Phil Shelley and passed unanimously called on the All Indian Pueblo Council to work with the New Mexico Historic Preservation Office, the city of Santa Fe, and the rest of the interested universe to find an alternative to demolition. Failing that, the committee asked that details of the unique structure be thoroughly documented before it is pulverized.

Like the City Council resolution passed Wednesday night, this is mostly a symbolic act. But maybe the tide is turning. Finally after all these weeks, the spark Ms. Abeyta lit seems on the verge of going national. Just this afternoon Paolo Soleri himself (through his Cosanti Foundation) promised to do what he could to preserve his creation, including raising money to keep it alive.

The antagonists in this story, school superintendent Everett Chavez and the Pueblo Council, are accustomed to ruling in darkness, deciding for themselves what is best for their people and tolerating no dissent. Maybe that won’t be so easy this time.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review

Live at Paolo Soleri: Stewart Udall’s Life

On Sunday morning as Tom Udall welcomed the people who had come to commemorate his father’s extraordinary life, the Senator explained why the event was taking place at the Paolo Soleri amphitheater at the Santa Fe Indian School. It was Stewart Udall who, as Secretary of Interior, contacted Mr. Soleri more than 40 years ago and asked him to work with students from the Institute of American Indian Arts to design and build the theater with its unique Flintstone-like style. Later when the elder Mr. Udall needed to raise money to defend the claims of Navajo uranium miners, he persuaded Pete Seeger and Edward Abbey to perform there. When his wife, Lee, died nine years ago, it seemed only fitting that the services take place, on Mother’s Day, at the Paolo Soleri. Now on Father’s Day it was Stewart’s turn.

Senator Tom Udall at the Paolo Soleri, June 20, 2010

“The Paolo Soleri is a very special place for us,” the Senator said. “It is specifically where dad asked that we do the celebration.”

Joshua Madalena, governor of Jemez Pueblo, gave a blessing, and one by one, friends, dignitaries, and family members took the stage. There were folk songs — “He was a Friend of Mine,” “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” and “This Land Is Your Land” — and readings from the grandchildren.

And throughout this all, there was not a mention of the fact that the unique amphitheater we were all sitting in is about to be destroyed.

At one point the Senator asked governors from the various tribes — who as members of the All Indian Pueblo Council have approved the demolition — to stand and take a bow. “Thank you,” Mr. Udall said, “for running a good school and focusing on education.” Tacit approval perhaps of Superintendent Everett Chavez’s repeated declarations that the theater must be removed because it has become inconsistent with the school’s “progressive” educational mission.

It was a morning of surreal ironies. We were reminded during the speeches that it was Stewart Udall who was so crucial to the passage of not just the Wilderness Act and the Endangered Species Act but also the National Historic Preservation Act, which, properly applied, might have saved all those buildings on the old campus as well as the Paolo Soleri. It’s too late now.

Calabaza Consultants, the Native-owned PR firm recently hired by the school to more efficiently deliver its obfuscations, has announced that two previously scheduled concerts (Lyle Lovett and Modest Mouse) will be allowed to continue before the Paolo Soleri is closed. In return the promoter, Jamie Lenfesty of Fan Man Productions, who stood to lose money if the shows were cancelled, grudgingly agreed to give up the fight. Not much more than a week ago, Mr. Lenfesty called on members of the New Mexico Cultural Properties Review Committee to help save the theater. “There will never be another Paolo Soleri,” he told them. “There is a spirit and a soul. Every musician I have had the pleasure of presenting there has left Paolo moved by its power.”

Now, in the press release announcing his dispensation, he recognized the “unfortunate reality” that the Paolo Soleri is on school property and agreed with the Pueblo Council that it “would be better suited to a different location where the activities of concert goers would not be deemed a threat to education and student life.”

In the end, it all came down to the bottom line.

George Johnson

The Santa Fe Review