copyright 2006 by George Johnson

Santa Fe Baldy. photo by George Johnson, copyright 2006

1. Retrofit Arithmetic (and Rainbarrel Economics)

2. The San Juan-Chama Shell Game

3. The Case of the Disappearing Aquifer

4. The Creative Hydrology of Suerte del Sur

5. The City, the County, and a Water Tax Revolt

6. Water Numerology at City Hall

(Our story thus far)

7. The Woman at Otowi Gauge

8. "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."

9. The Las Campanas Connection . . . desalination word games . . . and Aamodt South

(Our story continues)

10. The Engineering Solution

11. The Sorrows of San Acacio

12. The City's Dubious Water Report

13. Where the Water Went

14. Shutting Down the River Again

15. Picking on the Davises

16. The Tom Ford Webcam

17. Galen Buller's Day Off

18. Forgive and Forget

19. Election Postmortem

20. El Molino Gigante

21. Hotel Santa Fe. . . Mansion Watch . . . Water Watch

(Our story continues)

22. The Environmental Impact of Jennifer Jenkins

23. The Short-term Rental Racket . . . Water Watch . . . Mansion Watch . . . Surreal Estate

Our Story Continues:

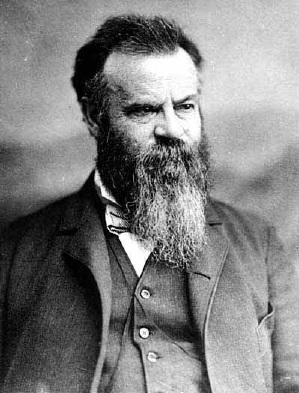

Around 1870 as homesteaders pushed beyond the 100th meridian and into the arid West, climatologists noticed a curious phenomenon. As towns and farms were settled, the amount of precipitation seemed to increase. "Rain follows the plow," they declared, theorizing that the planting of crops and trees and the exposure of tilled soil to the sky somehow stimulated the clouds to drop more water. Even the bustle of commerce -- the stomping of people and cattle and the motion of wagons and locomotives -- was said to shake a little more rain from the sky.

A few skeptics, like the explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell, recognized this as nonsense. In a few years, rainfall fell back to normal, and it became painfully clear that the brief burst of dampness had been an anomaly -- a random blip in the meteorological cycle.

A few skeptics, like the explorer and geologist John Wesley Powell, recognized this as nonsense. In a few years, rainfall fell back to normal, and it became painfully clear that the brief burst of dampness had been an anomaly -- a random blip in the meteorological cycle.

The plows didn't follow the rain back east. With rugged independence, the settlers stayed put on their free land and waited for the government to bring them water -- through aqueducts and canals. Phoenix became so wet that it developed a mosquito problem.

A hundred years from now historians may conclude that Santa Fe, in 2006, was seized with a similar fantasy: rain follows the backhoe. In the first few years of the 21st century, precipitation spiked and then plummeted to the lowest level in modern times. Per capita water consumption leapt to a five-year high. The great hope of the Buckman diversion seemed as intangible as ever, its estimated cost having octupled since it was first proposed from $20 million to $165 million with the city and county still fighting over how to pay the bills.

As chronicled here before, the project, if brought to completion, would simply maintain the status quo, providing no extra water for the sprawling developments -- Rancho Viejo, Las Soleras, Entrada Contenta, San Isidro Village, Colores del Sol . . . -- steadily making their way through the approval process. In place of real water, the developers were only being asked for promissory notes, paper rights from the same overtapped river -- down to one-third its normal flow -- that Albuquerque, Española, Rio Rancho and the pueblos were also coveting.

Hoping that rain follows tourists, the downtown hotels planned the addition of whole new wings and meeting halls, and the city broke ground on a new convention center. Nowhere was there an accountant tallying up a balance sheet -- how many acre-feet of water this new Santa Fe would require and where it would come from. Somehow Providence would provide. . . .

June 7, 2006

22. The Environmental Impact of Jennifer Jenkins

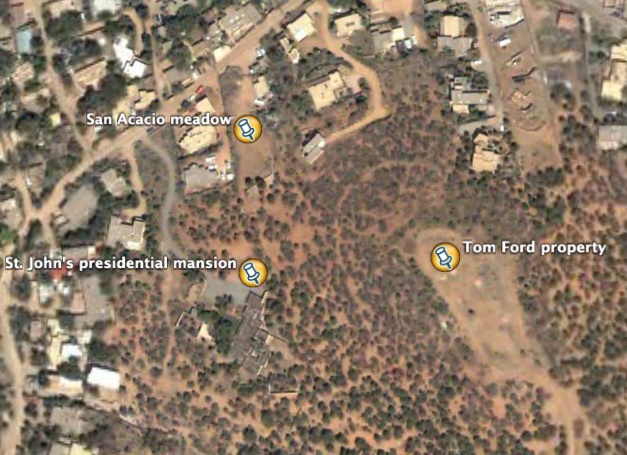

The first time I saw her in action was at the Randall Davies Audubon Center at the end of Canyon Road. It was just before Christmas and she was there to assuage several dozen neighbors perturbed at her client Tom Ford's plan to build a 16,000 square-foot estate on top of what some locals fondly call Talaya Hill. Mr. Ford, a famous fashion designer, was also there to charm the crowd with his compromising spirit and his need for eight times the floor space of an average homeowner. But it was Jennifer Jenkins, a tall blonde with a bit of a twang, who was running the show.

Ms. Jenkins makes her living shepherding unpopular projects through the city planning process. After agreeing to some modest concessions, Mr. Ford eventually won approval from the Historic Design Review Board for a slightly smaller house. Bitter feelings linger about the gargantuan scale of the project and its location on the most visible crest of the 10-acre site -- a neighborhood appeal is pending -- but the betting is good that Mr. Ford will prevail.

It is uncertain how much credit or blame Ms. Jenkins will deserve for the victory, but from all appearances she is on a roll. When the owner of a hillside meadow on the northwest slope of Talaya -- known for its picturesque family chapel -- wanted the right to build more houses than allowed by law, he hired Ms. Jenkins to push for a rezoning. Packing a small meeting room at Manderfield School with three generations of the owner's kin, she beseeched the neighbors to uphold family values by supporting the request to increase the value of the land. With no assurance that the upzoned property would not be sold to developers, her arguments were met with skepticism, and they turned out to be moot. Since the representative from the city didn't show up, the meeting was later declared invalid. For the time-being, the neighborhood was saved by the incompetence of city hall.

Last week, appearing before the planning commission, she was at it again, championing a couple who had purchased the artist Janet Lippincott's Canyon Road property a few months ago and wanted the rules changed so they could split it in two and double their money. The unhappiness of the neighbors wasn't a consideration -- the new buyers wouldn't be living there. The request, vigorously opposed by the Canyon Neighborhood Association, was turned down but is subject to appeal. Meanwhile Ms. Jenkins is preparing for the next session where she will argue the case of a developer with an even more audacious request: he wants his land on Old Taos Highway, purchased with the understanding that he could build four houses, rezoned to allow for 42 condominiums.

Ms. Jenkins is doing nothing unethical or illegal. She has simply found a niche in a society that grows greedier every day. Last year when a couple with a residence on the oldest part of Garcia Street wanted to demolish their 1,300-foot guest house and replace it with a 4,246-square-foot, two-unit condominium -- twice as big as the main house -- they turned to Ms. Jenkins. She and the owners' attorney -- Karl Sommer, Santa Fe's grandmaster at manipulating the land use rules -- lost that case too, but there are many more in the queue.

At the same planning commission meeting, Mr. Sommer was representing the acquirer of a grand old home on Buena Vista Street, just off Old Santa Fe Trail, with the rarest of rarities in this town -- a spacious, tree-shaded lot. Rather than luxuriating in the openness, he wants to adjust his property line so he can put three condominiums in his front yard. The request was denied, just barely, and now the case is expected to go to the City Council.

With real estate prices still booming, few Santa Fe investors are in danger of making anything less than a good profit. But apparently that is no longer enough. Unless the government supports your self-perceived right to achieve, at the expense of your neighbors, the maximum theoretical profit on your land, you have been oppressed and aggrieved. For a price, Ms. Jenkins or her equivalent stands ready to take up your cause.

June 13, 2006

23. The Short-Term Rental Racket

Last fall when a citizen's task force was appointed to investigate the short-term rental problem, there was rumored to be a hidden agenda. The sponsor of the move, Councilor Rebecca Wurzburger, is well connected with Santa Fe's real estate industry, both socially and professionally. Tony Rousselot, the Sotheby's agent who sold her 7,000+ square-foot house on Camino de Cruz Blanca (she now lives farther up the hill) is, with his wife, Janet Reed Rousselot, co-owner of The Management Group, the biggest broker of illegal vacation rentals in town. The Rousselots were among the many Santa Fe real estate operators who donated to the councilor's campaign.

When Mrs. Rousselot herself was appointed to the committee, while Dena Aquilina, president of the Historic Neighborhood Association, was blackballed, suspicions increased that this was all a ruse -- a furtive attempt to rezone Santa Fe's residential neighborhoods to allow for commercial lodging operations. Instead of enforcing the law, it would be changed to accommodate the councilor's friends.

At the hearings, the property managers put on a good show, rounding up workers -- maids, gardeners, handymen -- to testify that the illicit businesses were important to their livelihood. The owner of an illegal bed & breakfast declared that, if forced to obey the law, she would have to leave Santa Fe, predicting that her employees would "join the ranks of homeless people if they were out of jobs -- drug users, alcoholics." The New Mexican's editors, frequently dismissive of neighborhood concerns, came out in favor of legalizing the rentals, even letting their opinion spill over into the news pages: an otherwise objective report on the issue was headlined "Quaint and Cozy Short-term Rentals Could Be at Risk."

Throughout the deliberations, the violators continued to operate with impunity, while realtors assured investors that they could buy Santa Fe residences and surreptitiously convert them into inns. In a story in the New Mexican's business section, a representative for Kokopelli Property Management baldly stated that he was "mainly looking for people who want to buy homes for investment purposes" -- renting them by the day or week at a profit. It is a lucrative racket. At the artist Alexander Girard's old compound on Camino Delora, which was chopped into condos several years ago, one unit is being hired out for $550 a night with concierge service and a two-week minimum stay.

Last week the Rousselots got what they wanted: the task force recommended that the council overturn the ban. Under the proposal, vacation rentals would for the first time be regulated and licensed and the landlords required to pay the taxes -- lodging and gross receipts -- that so many of them have been evading. Maybe that would be an improvement over the prevailing lawlessness, but it would also be a betrayal -- of every homeowner who, playing by the rules, bought into what was supposed to be residential neighborhood.

Water Watch

Sunday's New Mexican carried an excellent package of articles by Staci Matlock on the crisis along the Rio Grande, where many times more water has been promised to cities, farmers, and developers than actually exists. I would take exception to her statement that the Buckman Diversion will give Santa Fe access to 5,605 acre-feet of "new" San Juan-Chama water. As noted before, that is the same amount used now. It will simply be taken directly from the river instead of being pumped from the ground. It's also not quite right that last year the city "relied primarily on water from the McClure and Nichols reservoirs." Even with all the rain, Santa Fe still took more than half its water, 54 percent, from the Buckman and city wells.

Those are small points. These stories, along with those Paul Weideman has written for, rather surprisingly, the real estate section, should be gathered into a booklet and made available to anyone interested in the water problem.

Mansion Watch

Sharing Sunday's page one was a story in which a local real estate agent boasts of selling the most expensive Santa Fe residence yet -- an 11,839-square-foot house in Las Campanas for $9.5 million. (Microsoft magnate Paul Allen paid an estimated $12 million for Sol y Sombra, the former O'Keeffe estate on Old Santa Fe Trail, but it also included a small conference center.) The broker, Neil Lyon, says he was both the buyer's and seller's agent. If he and his company got the customary 6 percent commission that would be $570,000.

Surreal Estate

June 18, 2006

The business section of this morning's New Mexican features a story on the local housing market that might be mistaken for a Santa Fe Association of Realtors press release. While houses in some cities are overvalued by as much as 102.6 percent, we learn, the figure for Santa Fe is a modest 21.7 percent. If you just bought a $600,000 home, rest assured that you only overpaid by about $130,000.

The article, which is based on a recent economic study, goes on to quote local realtors, who assure us that the market is fairly priced. What else would they say -- that their clients' houses are overvalued and that buyers should bid accordingly? One realtor makes the familiar claim, unchallenged by the reporter, that houses here are expensive because the City Council "controls everything." This would come as news to anyone witnessing the current construction frenzy encouraged by the developer-friendly Planning Commission. The weirdest comment of all is that high-end homes are languishing unsold not because they are overpriced but because there are so many of them. Supply in other words exceeds demand, which means the prices are, by definition, too high.

There are so many unwritten stories in this town about real estate speculation and the connections between developers and City Hall. This is what we get instead.

June 26, 2006

Both the Planning Commission and the Historic Design Review Board will be meeting this week, and a look at their agendas shows that it will be business as usual, with developers trying to squeeze more and more houses into the overcrowded, traffic-congested historic districts. A Texas outfit called Mountain Investments Inc. wants to add two houses at 523 Canyon Road, just east of Morningstar Gallery, while Jay Parks wants to tear down the house at 420 Arroyo Tenorio and replace it with two bigger ones. Two more houses are proposed on Gregory Street in the Don Gaspar Area Historic District.

Meanwhile at the Planning Commission, there will be an appeal, presumably by a neighbor, of an earlier decision to approve seven new lots on Montoya Circle, uphill from the corner of Palace and Canyon Road.

Outside the historic districts, the owner of 1034 and 1038 Old Taos Highway will try again to redesignate the two acres from "Residential -- Very Low Density" to "Residential -- High Density" to allow for a 25-unit condominium complex, while developers of something called the Vista Grande Subdivision want to create five new lots north of Circle Drive.

If all this is approved, there will be 42 new households near the center of town. According to studies by the Institute of Transportation Engineers that means between 200 and 400 more car trips per day on the crowded downtown streets, most of which could not be widened even if anyone wanted to. Additional water consumption will come to 3.4 to 4.5 million gallons a year.

All that in a week's work. Each of these boards meets approximately 26 times a year.

June 27, 2006

Last night I was watching the City Council on channel 16 when, just as Councilor Wurzburger was grilling developer Jeff Branch about where he was going to get water for his latest cookie-cutter subdivision, Cielo Azul, the electricity went out. I found a flashlight and candle, wondering if the councilors were also stumbling in the dark.

About 45 minutes later the power came back. "It was an act of God that brought us down," Mayor Coss quipped, "and an act of PNM that got us up again." After Councilor Ortiz pushed Mr. Branch and his lawyer, Karl Sommer, into agreeing to include more affordable housing, the council voted to annex the 40 acres and zone it to accommodate 201 residences. Several more items made their way through the agenda and finally, more than four hours into the evening session, came what I was waiting for: the San Acacio Neighborhood Association's appeal of the estate Tom Ford has planned for the Talaya reservoir site.

Displaying photographs of the "story poles," placed by the builder to show the elevations of the 15,862 square-foot compound, Peter Shoenfeld, the association's president, argued that it would loom over the old barrio, completely out of scale and character. He was marshaling his objections to the Historic board's decision not to consider this effect on the streetscape when the clock struck midnight and the television technicians abruptly pulled the plug.

It was a sad moment. Mr. Shoenfeld has been fighting for more than a decade to preserve what is the last undeveloped hilltop in the center of town -- a saga I'll recount in a future installment. It's history now. Though the news didn't make it into today's papers, the neighborhood lost its appeal. Mr. Ford will get his view of Santa Fe and Santa Feans will get their view of Mr. Ford's enormous mansion.

Russell Max Simon reports in this morning's Journal that, over the objections of more than 50 neighbors, the Planning Commission voted to rezone 1034-1038 Old Taos Highway to allow for 25 condos. (The New Mexican apparently didn't cover the meeting.) This project is one of the Jennifer Jenkins specials described here earlier, and the developer is none other than Kurt Young, one of the co-conspirators in the Santa Fe Grassroots affair.

Mr. Young, readers may recall, was campaign manager in 2004 for Eric Lujan, who sits on the Planning Commission. Mr. Lujan recused himself from the vote but without really explaining why. (He said some of his campaign contributors lived in the area.) It will be interesting to see if Carmichael Dominguez, the other Grassroots candidate, does the same when neighbors appeal the case to the City Council.

It's been a good week for Ms. Jenkins, who was also hired to push the Ford mansion through City Hall. Meanwhile she is continuing to press for rezoning 1270 Canyon Road to allow for more density. (The Planning Commission's unanimous denial of the plan is being appealed.)

July 1, 2006

July 2, 2006

Water Watch: The Sunday Papers

With the Rio Grande already overtapped, developers increasingly rely on  buying rights from the lower river and transferring them, on paper, for use in Santa Fe. In theory the seller stops irrigating, making up for the water the new subdivision will use. As noted here before, this involves some rather imaginative hydrology, and now we learn from Staci Matlock in The New Mexican that the situation may be even worse. She describes a scheme, involving "water banking," that might allow a farmer to sell his rights and go right on irrigating.

buying rights from the lower river and transferring them, on paper, for use in Santa Fe. In theory the seller stops irrigating, making up for the water the new subdivision will use. As noted here before, this involves some rather imaginative hydrology, and now we learn from Staci Matlock in The New Mexican that the situation may be even worse. She describes a scheme, involving "water banking," that might allow a farmer to sell his rights and go right on irrigating.

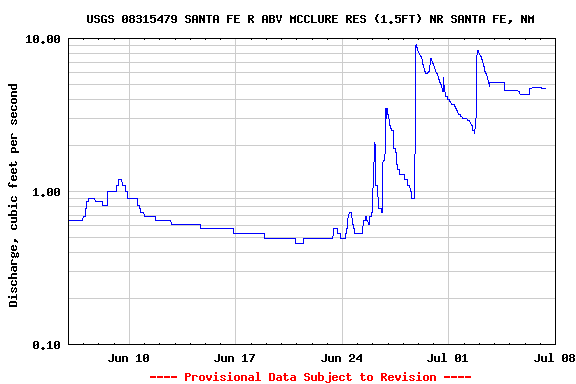

In another eye-opening article, City Dipping Deep Into Ground Water Supply, Russell Max Simon writes in the Journal that "Santa Fe is playing Russian roulette" -- mining most of this summer's water from an aquifer -- the Buckman well field -- that has already been badly depleted. (The graph at the right shows the plummeting level of a monitoring station there.) That in itself isn't news, but the story goes on to report that most of the pumping is from the four "emergency" wells approved during the 2002 drought -- and that neighboring landowners and irrigators are suing the city for impairing their own water supplies.

Though the story doesn't say so, this is just one of the pressures the Buckman field is facing. When the first wells were permitted in 1976, water from the Rio Grande was supposed to steadily trickle down and replenish the water table. But the riverbed hasn't been as porous as the hydrologists had hoped. The "cone of depression" from the Buckman field is believed to be sucking in water from the Tesuque and Pojoaque rivers. An article published in the State Engineer's newsletter, back in 2001, said that Santa Fe had enough rights to "meet the offsets" for the next eight years. So unless more rights have been accumulated, it sounds like the city might have to cut back its pumping as soon as 2009.

The Buckman diversion is supposed to be operating by then, taking up the slack. But that seems like a longshot. According to an article by Paul Weideman in the New Mexican's monthly real estate magazine, which also came out today, the project is only in its "draft preliminary design" stage. The city has learned that the river water is so dirty that it will require much more filtering than anticipated. Even when construction is done, it may take up to two more years to make sure the treatment plant is working.

It is jarring to read an article like that surrounded by some 120 pages of real estate ads. The same issue features a profile of a local realtor who says she has a master's degree in "practical spirituality." Maybe that is what it will take to find a way out of this mess.

July 7, 2006

The flow into McClure Reservoir

Coming Next: Death Comes for the Archbishop's Garden

Coming Soon: The Battle for Talaya Hill

The Andrew and Sydney Davis Webcam

The Santa Fe Review

More links:

See the current flow of the Santa Fe River above McClure Reservoir

with

the USGS automated gauge.

The Otowi

gauge shows the flow of the Rio Grande north of Santa Fe.

Santa Fe water information, a collection of documents and links