copyright 2004 by George Johnson

Scottsdale City Hall in January, photo by George Johnson

1. Retrofit Arithmetic (and Rainbarrel Economics)

2. The San Juan-Chama Shell Game

3. The Case of the Disappearing Aquifer

4. The Creative Hydrology of Suerte del Sur

5. The City, the County, and a Water Tax Revolt

6. Water Numerology at City Hall . . . and a followup

1. Retrofit Arithmetic

John McCarthy, a mathematician at Stanford University, has a saying he likes to append to the end of his Internet postings: "He who refuses to do arithmetic is doomed to talk nonsense." It is a slogan that might be taken to heart by anyone writing about water in northern New Mexico.

Consider, for example, a short paragraph that appeared on August 7th in the New Mexican about Albuquerque developer Jay Parks's plan to build a new subdivision on a 19-acre parcel near Museum Hill:

"Water is a question," he said. For him to meet city ordinances, he would have to replace 240 existing toilets throughout the city with low-flow toilets so his new structures do not require additional water supplies.

I've added the italics, for it is not Mr. Parks speaking here (the quotation has ended) but the reporter, stating what is apparently being presented as undisputed fact. Can it be possible to add a small neighborhood -- this would be 21 new houses -- to Santa Fe's water system without increasing consumption by even a gallon? That was the promise of the retrofit ordinance when it was passed by the City Council two years ago, as a compromise aimed at heading off a building moratorium:

Any building permit or water hook-up shall be issued or granted only if it is in compliance with all sections of Chapter 14 and when the applicant demonstrates that the water demands created by the use of the structures for which the building permit, water hook-up or development approval is sought will be entirely offset ("Project Water Offset") in accordance with the Annual Water Budget Procedures and 14-8.13(F).

[Again, the italics have been added. Chapter 14 is the city development code and Section 8.13(F) spells out the retrofit requirements.]

So let's do the arithmetic. A study by the American Water Works Association, a nonprofit organization based in Denver, estimates that each of us flushes the toilet five times a day. (Of course one toilet might be used by more than one person, and one person might use more than one toilet -- at school or at work, for example. But on average, five daily flushes per fixture seems like a pretty reasonable figure.) A retrofitted toilet saves almost two gallons per flush, using 1.6 instead of 3.5 gallons, amounting to about ten gallons a day and 3,650 gallons a year. For every new house built, Santa Fe contractors are required to replace between eight and twelve existing water-guzzlers (it depends on the size of the lot). If we take ten as the average, that would mean an annual savings of some 36,500 gallons, a significant amount of conservation.

But how much water does one of the new houses use? The same study by the water association estimated that the average household in the United States consumes 146,000 gallons a year or 12,166 gallons a month. Santa Feans do better than that -- 8,000 to 10,000 gallons a month is typical. The city estimates 7,000 gallons as the monthly average, so multiply that by 12. For a new house, 36,500 gallons is saved but 84,000 is consumed -- a deficit of 47,500 gallons.

So even with the retrofits, the Museum Hill development would draw nearly another million gallons a year from Santa Fe's water supply. Every year another 700 or so new houses are approved for construction. (I'm extrapolating from figures in the most recent Santa Fe Trends report.) If each one of those houses is incurring a water deficit of 47,500 gallons, then more than 30 million additional gallons -- over 100 acre-feet -- is extracted from the system each year.

A calculation like this is only as good as the assumptions built into it, but these seem like pretty conservative ones. Most houses are probably constructed on average-size lots, requiring only eight retrofits, and many residents already conserve water by limiting the number of flushes to less than the average five.

The deciding point is whether Santa Fe's water consumption is staying flat, or even diminishing. According to the city's official water reports, last week we used 11.61 million gallons a day, compared with 9.67 million for the same week in 2003 and 8.75 million in 2002.

Similar figures prevailed throughout the summer, with more water being used each year. In the dead of winter, however, when no one is irrigating, there is an improvement. For the week ending January 19, for example, we used 6.43 million gallons a day, compared with 7.21 million in 2003 and 7.96 million in 2002. There are so many variables in the water equation, that it is hard to draw firm conclusions. Maybe a case can be made that retrofitting is reducing the overall amount of water Santa Feans use inside their homes, but not when you include irrigation. Even with xeriscaping, each new house means more plants to water. House by house, the size of the water deficit continues to grow.

Sunday morning, September 19th

It rained an inch last night, enough to overflow our rainbarrels -- 440 gallons of new water for irrigation in the usually arid weeks before the first freeze. Before I started capturing it seven years ago, the water poured off the roof, across the patio, and into an old acequia. From there it flowed, when there was really a downpour, down the hill and into a storm drain that leads a few blocks to the Santa Fe River. Water here costs less than half a cent a gallon -- 43/100 of a penny -- so my eight barrels full is worth approximately $1.89. The investment (about $200 for barrels, hoses, submersible pump, etc.) barely pays for itself, but the system helps avoid accidentally exceeding the 10,000-gallon threshold where the city's Water Drought Emergency Surcharge kicks in. That can add up quickly. But we're nowhere near that level this month and they come to read the meter tomorrow.

I'm collecting this run-off from a roof surface of about 2,000 square feet. That means in a normal year, when we receive 12 inches of precipitation, a full foot, I would potentially reap 2,000 cubic feet from the sky. A cubic foot is about seven and a half gallons, so the annual harvest would be 15,000 gallons. That's about $65 worth of water, or would be if I were equipped to collect snow melt in the winter. In late autumn the barrels are turned upside down to keep them from bursting with ice.

Like everything to do with water, this is a zero-sum game. Each gallon I'm keeping to use on the gardens might otherwise help nourish the cottonwoods and willows down along the bosque (I don't regret depriving the Siberian elms.) Of course my roof water, and probably all the roof water collected in the neighborhood, is a tiny drop in the bucket. It wouldn't be missed at all if it weren't for the upstream dams. At this moment, the surprise September rain (a kink in the jetstream allowed Tropical Storm Javier to come up from the Baja) has pushed the gauge above McClure Reservoir to a whopping five and a half cubic feet a second -- nearly 150,000 gallons an hour, the highest it's been for a while.

This gauge marks the point where the river changes from wild to tame. Just downstream, the flow is impounded and chlorinated and pumped into the ever-expanding labyrinth of the municipal water works. The only water left for the riverbed comes from occasional flashfloods. Eventually a portion of this weekend's hydrological windfall will reenter the river on the other side of town, as effluent discharged from the treatment plant. But beween these two points, where the river runs (or used to) along the Alameda, the cottonwoods continue to die. This being Santa Fe, the city's response has been to hire an artist to turn some of the stumps into chainsaw sculptures, which at least have the advantage of not having to be watered.

September 29, 2004

Since the last installment, almost another inch of rain has accumulated in the backyard gauge. That's 1,250 gallons of runoff from a 2,000-square-foot roof. The barrels, of course, were already brim full from last week's rain, and with the ground saturated there has been no need to irrigate. Such is the feast-or-famine nature of rainbarrel economics. Unless you have a huge underground storage tank, you always end up with more water than you need in the wet times and not enough (or none) when it is dry.

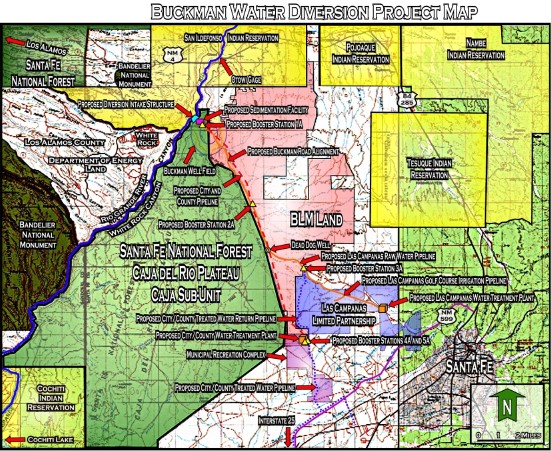

2. The San Juan-Chama Shell Game

This was the headline: CITY, COUNTY CONSIDER RIO GRANDE DIVERSION. And this is how the story began: "Faced with low snowpack and the prospect of a dry year ahead, Santa Fe city and county governments are jointly studying the possibility of building a structure to take water directly from the Rio Grande to supplement water supplies." The final report, a city water official estimated, would take half a year to complete. This would be followed by 18 months of planning and legal work and, depending on "unpredictable political and economic factors," another 18 months for construction -- altogether about four years.

The story appeared in the New Mexican on March 22, 1996, eight and a half years ago. Last week, a brief report on page B1 provided a progress report: city and county officials are still arguing over how  to pay for the project, which is nowhere near breaking ground. The estimated cost has crept from $20 million to $100 million -- or maybe $120 million, the figure used in Journal North's story last Sunday. The anticipated completion date is now 2008 . . . if voters approve a county property tax hike in November and a city sales tax hike next March, and if the federal government agrees to pick up most of the tab. Santa Fe, it seems, is on a treadmill running eagerly toward a carrot dangling perpetually out of reach -- always four years away.

to pay for the project, which is nowhere near breaking ground. The estimated cost has crept from $20 million to $100 million -- or maybe $120 million, the figure used in Journal North's story last Sunday. The anticipated completion date is now 2008 . . . if voters approve a county property tax hike in November and a city sales tax hike next March, and if the federal government agrees to pick up most of the tab. Santa Fe, it seems, is on a treadmill running eagerly toward a carrot dangling perpetually out of reach -- always four years away.

While the estimated price continues to rise, the amount of water the project promises to deliver has been reduced again and again -- or so it appears to anyone trying to follow this confusing hydrological shell game. Early on, it was common to hear that for lack of a diversion dam, Santa Fe has been letting 5,605 acre-feet of water -- its full share from the San Juan-Chama Diversion Project -- flow down the Rio Grande every year. That would be enough to supply 15,000 to 20,000 houses.

Of course the water is not actually being forfeited -- it is stored upstream in reservoirs on the Chama River, like Heron Dam. But, as soon became clear (through studies by citizens groups and Ben Neary's reporting in the New Mexican), this is not the bounty it once seemed. Every year some 30 to 40 percent of the water is already being used to "offset" the effects of pumping from the city's main source, the Buckman well field. Since the early 1970s, when the first wells were drilled near Diablo Canyon along the Rio Grande, the underground water table has dropped by hundreds of feet. To make up for the deficit, this mining of ancient groundwater, Santa Fe must release water from Heron -- currently 2,600 acre-feet a year -- the theory being that the extra flow will trickle down and replenish the aquifer.

Over the years, Santa Feans have learned of still more demands on the water. When Elephant Butte reservoir in southern New Mexico falls below 400,000 acre-feet, New Mexico cannot (under the Rio Grande Compact) fill its dams on the Santa Fe River -- Nichols and McClure -- unless it surrenders, for delivery to Texas, a compensating amount of San Juan-Chama water. Still more of the water must be returned annually to the river as payment for the costs of upstream storage.

The biggest bombshell came in a New Mexican story on July 3 by Mr. Neary and the city hall reporter, Tom Sharpe. It turns out that once we built the Rio Grande diversion, we still would not be able to divert any water. The Buckman field has been so severely overpumped that even if the wells were shut down completely, we would be paying back all the water we have "borrowed" from the aquifer for many years to come -- by letting San Juan-Chama water flow out of Heron, past the city, and on down the Rio Grande.

So in addition to the cost of building the dam and operating it -- treating the polluted surface water to the standard of what is now being pumped from the ground -- the city needed more Rio Grande water rights. Hence the agreement, signed this summer, to lease an additional 3,000 acre-feet from the Jicarilla Apache tribe for $1.5 million a year, a price that will be allowed to rise in the future to several times that amount.

The Jicarilla water will essentially go to recharge the aquifer, slowly making up for what we have already consumed. That leaves us free to divert the full 5,605 acre-feet of the long awaited San Juan-Chama allotment. But this will not be extra water. Santa Fe already pumps between 5,000 and 6,000 acre-feet a year from the Buckman field. When the dam is built and the pumps are turned off, we will not be getting any more water than before.

Since continued pumping of the Buckman field is considered unsustainable, there are reasons to skim dirty water from the surface of the river rather than to pump cleaner water from below. But what this long, expensive effort amounts to is not what had been so eagerly anticipated: more water to support growth. That would require buying still more Rio Grande water rights or applying to the State Engineer for "return flow credits" -- another shell game in which we would divert more water than we actually own under the theory that a portion of it eventually returns as treated sewage south of town. Meanwhile the Rio Grande diversion project and the lease with Jicarilla will simply allow Santa Fe to maintain the same precarious position as the Red Queen in "Alice in Wonderland," who must run as fast as she can just to keep from falling behind.

3. The Case of the Disappearing Aquifer

When I was growing up in Albuquerque in the 1960s, my father would talk, with a sense of wonder, about how our city sat on top of an enormous underground lake. So vast and deep was this aquifer that there would never be a reason to worry about water. That was the common wisdom, and so the city continued to expand, more than doubling in size by the early 1990s. Only then did it become clear that something was going wrong.

According to theory, water from the Rio Grande would continually seep down through the sands of the river bank and replenish the underground supply. With the water table dropping rapidly, the city called upon hydrologists to investigate.

It turned out that seepage from the river was so gradual that half the water the city was pumping was not being replenished after all. Like Santa Fe, Albuquerque was mining ground water. A resource that had accumulated over millions of years was being sucked up in a matter of decades. So Albuquerque cast its eyes northward, to the San Juan-Chama Diversion Project.

Since the early 1970s the city had contracted for rights to 48,200 acre-feet a year of this water, which is imported from the San Juan River Basin in Colorado by way of a tunnel drilled through the Continental Divide. From there it enters the Rio Chama, which carries it to the Rio Grande. Each year Albuquerque had been storing its share up north behind Abiquiu Dam and releasing it as needed to make up -- or so it believed -- for the water it was pumping from below. It was playing the San Juan-Chama shell game. Once the emptiness of this hydrological gesture became apparent, the city began its own plans for a diversion dam, to take its water directly from the river.

There are other claims to San Juan-Chama water as well. Next in size, at 20,900 acre-feet is the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, a mammoth irrigation project supplying farms from Cochiti south to Socorro. Then comes the Jicarilla Apaches with 6,500 acre-feet and Santa Fe with 5,605 acre-feet. Here is the list:

|

Altogether that is 86,210 acre-feet a year. This is not, however, what hydrologists call "wet water" (a term that seems like the linguistic inverse of an oxymoron) but "paper water." Its usefulness depends on how much real water is in the river. According to the most recent annual report from the office of the New Mexico State Engineer, the entire amount of water delivered by the San Juan-Chama project in 2002 was 6,300 acre-feet. That was the lowest ever, and delivery has been better since. But even in the wettest years, there is far more paper water in the Rio Grande than the kind you can drink.

4. The Creative Hydrology of Suerte del Sur

The disconnect between wet water and paper water will soon come to a head in the case of Gerald Peters and Suerte del Sur, the development of 264 houses (with clubhouse and stables) that he intends to build just northwest of Santa Fe. I was puzzled by the name -- it means "Luck of the South" -- until I read about Mr. Peters's plan to provide his development with water. Having recently dug a 2,000-foot-deep "exploratory well" -- a common way of getting a foot in the aquifer -- he has applied to the state for permission to transfer 188 acre-feet of water rights (61 million gallons a year) from farmland in Socorro, in southern New Mexico, to the new subdivision.

Mr. Peters will not, of course, be building a pipeline and pumping the water 140 miles uphill to Santa Fe. An engineering project of that scale must be beyond even his considerable resources. The conveyance, if it is approved, will take place entirely on paper in the office of the State Engineer, the administrator of water law in New Mexico. In return for surrendering his right to pump the water from the southern Rio Grande for agriculture, he would be allowed to take it instead from the well at Suerte del Sur.

In theory there is a loose hydrological connection between the Rio Grande and Mr. Peters's well, which is about eight miles away. Any water pumped from the ground eventually lowers the level of the river, as some of it trickles down to fill the artifically created void. Retiring water rights at Socorro may help compensate the farms and cities farther downstream, but it is hard to see how Santa Fe's own aquifer would benefit. Any effect, if there is one, would be measured not in months or years but in geologic time.

That is how the game is played. You buy a portfolio of paper water and with a few strokes of the pen from the State Engineer, voila, you are allowed to pump real water from the ground.

5. The City, the County, and a Water Tax Revolt

When Santa Fe the city and Santa Fe the county recently agreed on how to split up the money and the water involved with the Buckman Diversion project, each side knew it had the other over a barrel. To have any chance of getting substantial state and Federal funding, the city needed the county's cooperation in forging a regional water plan. Anything less, the theory went, would be impossible to sell in Washington or at the Roundhouse. If the city didn't agree to the county's terms, one commissioner warned, it would simply drill more wells, further depleting the aquifer that everybody depends upon.

On the other hand, without a partnership with the city, the county would be hard pressed to get access to its San Juan-Chama water -- 375 of the 5,605 acre feet earmarked for the Santa Fe metropolitan area -- plus any additional Rio Grande rights it manages to secure.

So came the compromise. Judging from a copy of the document, the bottom line is this: the county is paying more money than it had intended, while the city is surrendering more water and a great deal of control. The result will inevitably be more development beyond the city limits, with the southern flatlands becoming more and more like Rio Rancho, the Albuquerque suburb that has boomed over the years into a city of its own.

The total capacity of the diversion dam, 8,730 acre-feet, will be divided as follows: the city will get 5,230 acre-feet, its full San Juan-Chama allotment. (This, of course, is no more water than it is already using -- it will just be taking it directly from the river instead of the Buckman well field.) The county, for its part, will get 1,700 acre-feet -- its San Juan-Chama portion plus any other rights it can obtain. (Las Campanas, which will also pay for part of the system, gets 1,800 acre-feet.)

This part of the deal is not really new. The city maintains the status quo while the county gets more water for development. Where the city made some headway was in getting the county to pay for half the building costs. (This will begin with a $30 million contribution from each side.) This seems like a significant concession, since most of the diverted water will still go to businesses and residents within the city limits. But in return, the county extracted considerable concessions of its own.

First of all is the matter of the "wheeling agreement," under which the city has been obliged to sell the county up to 500 acre-feet a year. (The county gets the water by hooking into the city mains at a point on the south end of town.) The assumption had been that the arrangement was temporary -- a way to keep the county afloat until a diversion dam is built. Under the new agreement, the sales will continue "in perpetuity," something that no one at City Hall can be happy about. This water is in addition to the 1,700 acre-feet that will come from the diversion. Moreover, whenever drought causes the county's draw to fall below half that level -- 850 acre-feet -- the city must make up the difference with water of its own. Finally, the county will still be allowed to drill more wells.

There are other wrinkles, which will be the subject of future installments. But any way you look at it, the compromise seems like a wobbly step toward the ultimate goal of ending the region's addiction to the diminishing pool of groundwater. In times of drought, like now, we'll be back to pumping the aquifer. And nothing in the agreement stipulates that any of the river water will go toward serving existing county residents (as opposed to new subdivisions) and reining in the profusion of private wells.

In fact there are already signs of a backlash from residents who feel that the Buckman Diversion is just one more way to get them to subsidize the costs of unrestricted real estate speculation. A few letters to the editor have recently appeared in the New Mexican urging Santa Feans to vote against a county bond issue on the November ballot that would raise property taxes to help pay for the project. This week Santa Fe Water Crisis, a web site run by William Salman (of the family that owns the Salman Raspberry Ranch, near Mora, and Santa Fe Greenhouses), argued that approving the proposal would amount to giving the county a "blank check" when it "has not provided details on how the money would be spent and where the actual water would be found. The authorization of this massive expenditure is very likely to spur development beyond sustainable limits, and the County has not indicated what controls if any it intends to enforce."

Come November 2 we'll see how many others feel this way. If the bond issue fails it will be back to square zero.

6. Water Numerology at City Hall

This week's City Council meeting exhibited once again the irrational exuberance that overtakes some of our elected leaders when it comes to the subject of Santa Fe's water supply. As reported in the New Mexican by Henry Lopez, city staff informed the Council that, in a good year, Santa Fe's water system -- its well fields and the Santa Fe River reservoirs -- is capable of producing 10,600 acre-feet. Counting current use and water already committed to future subdivisions, demand is expected to rise in coming years to between 13,500 and 18,000 acre-feet.

Putting aside the reported shortfall, the Council proceeded to approve water hookups for two more projects in the county. The principals are two of the biggest developers in town: Richard "Dickie" Montoya and, again, Gerald Peters.

Mr. Montoya's Village Plaza will consist of 48 acres of housing and commercial space. The Peters organization's Casa Rufina Senior Apartments will consist of 120 units on land zoned for only 16 residences (the county obligingly granted a "variance" but did not provide a guarantee of water). This same enterprise used to be called the Stone Creek Senior Affordable Housing Project and was a subject of controversy last year.

According to the New Mexican report, some councilors insisted that city staff was underestimating the amount of water available for more development. What about the four new wells that have been drilled but are not yet on line? Or the savings from the toilet retrofit program? We've seen, however, in an earlier installment that any savings from low-flow plumbing is far outweighed by the amount of water consumed by each new house. And the wells (Buckman 10 through 13) will increase the depletion of the beleaguered aquifer, borrowing more water that will ultimately have to be repaid.

Here is another interesting bit of numerology: Casa Rufina's developers estimated that the project would require 8.32 acre-feet of water -- less than 2,000 gallons per unit each month. How each of the elderly residents will manage to consume a fraction as much water as an average household was not explained.

The fantasy continued in today's Journal North, with city councilor David Pfeffer repeating the retrofit myth: that because of the program, the numerous real estate developments the Council continues to approve are actually not using any new water.

Pfeffer said a public misunderstanding persists that the city is using "new water" when it approves development and ties developments outside city limits into city water lines. Not true, Pfeffer maintained. Those developments are using "water already in the pipes" saved by the retrofits, he said.

As basic arithmetic shows, this simply isn't true.

The story also repeats uncritically the city's official claim that it has "offset 483 acre-feet of water, 157,386,033 gallons, with the 10,000 [low-flow] toilets, meaning that much water was saved by retrofits." It would be interesting to know where that number came from. Assuming that people are not flushing twice, 10,000 retrofits conceivably might save about 36,500,000 gallons a year (10,000 toilets x 10 gallons a day x 365) -- four times less than the city is claiming.

Another way to estimate the savings would be to compare total consumption this year with total consumption in the past. But if Santa Feans are using less water, how much is attributable to more rainfall (this autumn has been the wettest in years), less landscape irrigation (i.e. letting our parks die), more rain barrels, shorter showers, the restrictions on residential car washing, fewer glasses of water served in restaurants, the substitution of treated effluent for potable water, etc, etc. Perhaps City Hall has developed a complex hydrological model taking all these factors into account. We'll never know, unless reporters start asking harder questions.

Here is another matter deserving scrutiny: the City Water Budget (section F, subsection 4a) states that to receive a building permit, a new dwelling must retrofit between eight and twelve fixtures for each new fixture installed. But the city has only been requiring eight to twelve fixtures in total for each new house -- quite a few less than the ordinance seems to call for.

In a followup to his earlier story, the New Mexican's Henry Lopez fleshes out some of the details of the two county developments that will be getting city water, including a provision under which the Santa Fe government could eventually buy the Casa Rufina senior complex. The amount of water the project will use is now reported as 9.97 acre-feet, which apparently includes landscaping, a clubhouse, and a community kitchen. That is not in the story but in a letter I found, dated Oct. 8, 2003, from the State Engineer expressing incredulity at the numbers. (This was back when the project was still being called Stone Creek.)

As in the earlier story, no connection is drawn between Casa Rufina and its previous incarnation. Each plan consists of 120 apartments at the corner of Rufina and Henry Lynch Road, and each is estimating water consumption of precisely 9.97 acre-feet, but from the press coverage these could be two entirely different projects. Is Mr. Peters's Santa Fe Art Foundation still the developer? Has ownership changed hands? This is an important part of the story.

Mr. Montoya's development is now described as consisting of "86 housing units and more than 51,000 square feet of space for commercial uses including eateries, retail shops and a service station." (Journal North had reported 75,000 square feet of business development.) Forty percent of the residences will be "affordable housing." More about that later.

Meanwhile, Mr. Peters's application to transfer water rights upstream from Socorro to Santa Fe has been rejected by the State Engineer. A letter to the Peters Corporation sent last week states that the well at Suerte del Sur will cause depletions to the south at La Cienega Springs and to the north in the Rio Tesuque and Rio Pojoaque basins: "These are depletions not offset through retirement of Middle Rio Grande water rights."

This seems to mean that the developers will have to buy rights on the Tesuque and Pojoaque, which are extremely expensive, when they are available at all. According to the 1995 Thaw Report (page 12), they can go for as much as $50,000 per acre-foot. That is why the city has elected to build the Buckman Diversion rather than trying to buy the rights it would need to make up for the damage to these streams caused by the overpumping of the Buckman wells.

It will be interesting to see what happens next. Perhaps Mr. Peters will come to the City Council and ask it to extend its water mains -- in return for making half the residences in the luxury development affordable housing.

November 2, 2004

In another development in the Suerte del Sur situation, a lawyer for the Peters Corporation tells reporter Julie Anne Grimm that the State Engineer's decision does not pose an insurmountable barrier: the company already has most of the offsetting water rights it needs on the Tesuque and Pojoaque and for La Cienega Springs.

This raises two questions: (1) Why then were the developers trying to play the shell game with the Socorro rights? and (2) How are they going to get around the restrictions on transferring Tesuque and Pojoaque water across the Otowi Gauge? This is essentially a water meter located on the Rio Grande at San Ildefonso Pueblo. Under the Rio Grande Compact, New Mexico must deliver a percentage of the measured flow to Texas. Transferring rights from the north side of the gauge to the south throws off the calculations, to the extent that all three signatories to the pact -- Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado -- would have to return to the table and agree to an amendment. This is a can of worms unlikely to be opened for the benefit of a single developer.

There are other complications as well, which I will save for a later installment. This will involve taking a look at the proposed settlement of the Aamodt suit, which includes a little-publicized provision that could lead to Santa Fe (city and county) importing vast amounts of water from northern New Mexico -- a scenario some people are comparing to the semi-fictional water grab in the movie "Chinatown." If this comes to pass, life in Santa Fe and in the villages to the north will never be the same.

Where there is a will there is a way. Just when it seemed that Gerald Peters was facing a considerable hurdle in his plan for a new luxury subdivision, the County Commission has come rushing to the rescue. According to a report in this morning's Journal North, the commissioners are strongly considering eliminating the requirement that developers must secure a water supply before seeking approval of their "master plan." Instead they would simply have to submit an analysis of how the new development might affect neighboring water supplies.

Eventually they would still have to come up with water rights to get final approval, but the change would give them more breathing room.

Only one member of the commission is quoted as objecting to the move: "We're here to protect the public, not land developers," Commissioner Jack Sullivan said. Commissioner (and French & French Realtor) Paul Duran pushed for loosening the rules.

In today's New Mexican, editorial writer Bill Waters gives his take on Commissioner Duran's effort:

The swan song being sung by Paul Duran, who takes his leave from the Board of Santa Fe County Commissioners at year's end, is music to the ears of real-estate developers. . . . His point, accompanied by stirring arias on the sanctity of property rights: It costs lots of money to secure water rights. And what if a developer goes to all that expense, then can't get his project approved? It isn't fair. But is it any fairer to lead the developer down the primrose path of approval during the master-planning stage, then deny the go-ahead after he's paid planners, architects, promoters and others to push the project to the point of pouring concrete? Left unspoken is the notion that a developer might be able to persuade the commissioners to approve so much of the project that, when the matter of water comes up, they'll say what the heck; we're this far along, so just hook it up to your well or the nearest water line -- and worry later about where the water's coming from.

Coming Soon: The Lot Split Game

The Santa Fe Review

More links:

Santa Fe water information, a collection of documents and links